‘Sovereign citizen’ case reveals squatters targeting vacant Las Vegas homes

Carol and Myles Catania were living in a hotel, having been evicted from their suburban Las Vegas house, when they got a call from someone named Tom. He didn’t give his last name and wouldn’t say where he worked, but he offered them a sliver of good news: They could come back for their stuff.

When they drove up, however, the bank-owned home was getting tossed. Strangers were throwing their belongings into trash bags, and one man told a laborer that once they got the safes open, he could take what he wanted.

A few days later, a man named Thomas Benson sued for the property. And several weeks after that, he said police and federal agents raided his house with semi-automatic rifles.

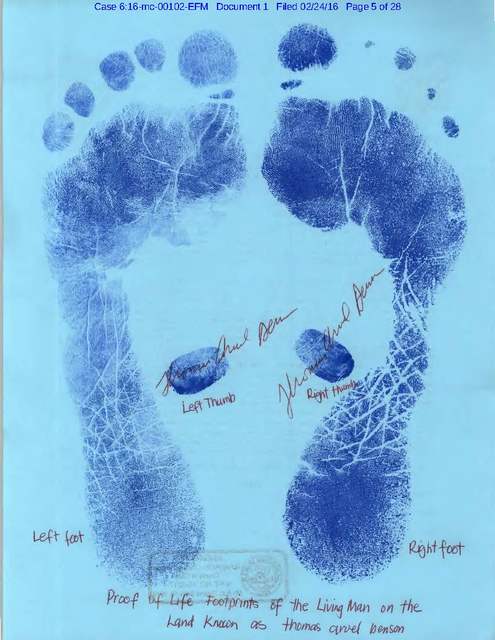

Benson is a purported “sovereign citizen,” or a follower of anti-government ideology whose adherents are known for financial scams, nonsensical writings and occasional violence. He has said in court papers that he’s “not a person” and showed his “proof of life” with blue footprints, though he’s also been charged at least twice in Clark County over fraudulent checks.

His saga offers a glimpse at the bizarre and often criminal world of sovereign citizens and shows how Las Vegas, despite the improved housing market, still grapples with a dark, lingering side effect of the recession: squatters and others targeting vacant homes.

The Review-Journal did not find accusations that Benson moved into the Catanias’ former home, a 2-acre spread with a guest house and a roughly 5,400-square-foot main house off Ann Road and the 215 Beltway. But people apparently had taken over the northwest valley property around the time he sued. Wooden barricades blocked part of the driveway, and a No Trespassing sign out front had the name and phone number of Benson’s partner in the lawsuit.

Sovereign citizens aren’t new to Las Vegas and are involved with squatter homes around the country. They file bogus deeds for vacant properties, change the locks and “rent” them out, said Mark Pitcavage, a senior research fellow at the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism.

Las Vegas has grappled with a widespread squatter problem the past few years, enabled by the valley’s thousands of vacant homes and growing use of fake leases. But locally, sovereigns’ involvement in these scams appears rare.

Las Vegas police Lt. Nick Farese of the Northwest Area Command, which in recent years had the most squatter calls in the Metropolitan Police Department, said sovereigns are “relatively new” here when it comes to squatter homes and aren’t “super-prevalent.”

“This is obviously the biggest one I’m involved with thus far,” he said.

Henderson and North Las Vegas police said they hadn’t come across sovereigns when dealing with squatter homes.

“I can only imagine what a cluster that’s going to turn out to be,” said Officer Scott Vaughn, who heads the North Las Vegas police department’s squatter enforcement.

‘NO DOUBT’

Benson has denied Metro’s accusation that he follows sovereign ideology, but Pitcavage looked at some court filings by Benson that the Review-Journal sent him and thought otherwise.

“Oh, please,” Pitcavage said. “There’s no doubt he’s a sovereign citizen.”

Metro declined to comment on details of Benson’s case, including the raid, citing an open investigation and litigation, as Benson sued the department this year over a traffic stop.

The U.S. Treasury Department did not respond to a request for comment on Benson’s claim that its agents took part in the raid. The FBI’s Las Vegas office declined to comment on his claim that FBI agents participated, and the Nevada Attorney General’s Office, which prosecutes real estate fraud, declined comment altogether.

When the Review-Journal initially called Benson for comment, he said, “I’m not sure what you’re talking about,” and hung up before the R-J could question him on the sovereign citizen accusations. A second attempt to reach him weeks later was unsuccessful.

It’s unclear what the 55-year-old Benson does for a living. He claimed in court papers two years ago that he was a “business assistant” for a foundation that doesn’t appear to exist and said this summer that he sells a coffee product.

He’s also been accused of offering “legal kits” to help people stall evictions. And after Benson allegedly wrote a bogus $18,000 check, his accused accomplice told a detective that he had met Benson at a financial seminar where Benson was a “key speaker,” court records say.

At least one thing seems certain: Benson left stacks of bizarre court papers in his wake in recent years.

■ A filing in the check case said Benson was an “official carriage registered under the universal post office” and authorized to carry “sacred cargo beyond the sea.”

■ He filed in Kansas federal court an “Ecclesiastical Deed Poll” that said he is “living flesh and blood, sentient man.” The filing included a page with footprints and thumbprints in blue ink labeled “Proof of Life Footprints of the Living Man on the Land Known as thomas arvel benson.”

■ He incorporated a business in Missouri called THOMAS ARVEL BENSON and filed a $499,999,999.99 lien against it.

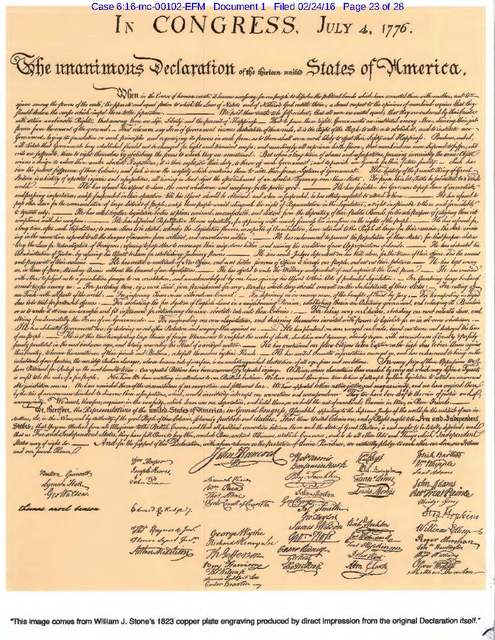

■ His filings have featured red thumbprints, crests or coats of arms and a copy of the Declaration of Independence that appears to include the signature of one “thomas arvel benson” not far from John Hancock’s.

Metro has accused Benson more than once of being a sovereign. A detective investigating the $18,000 check reported in 2013 that he recognized Benson from “several other investigations” and that Benson “is believed to subscribe” to sovereign ideology.

The case was later dismissed, apparently in a deal that led to a guilty plea in another check case, court records indicate. He received probation and a suspended prison sentence in that one.

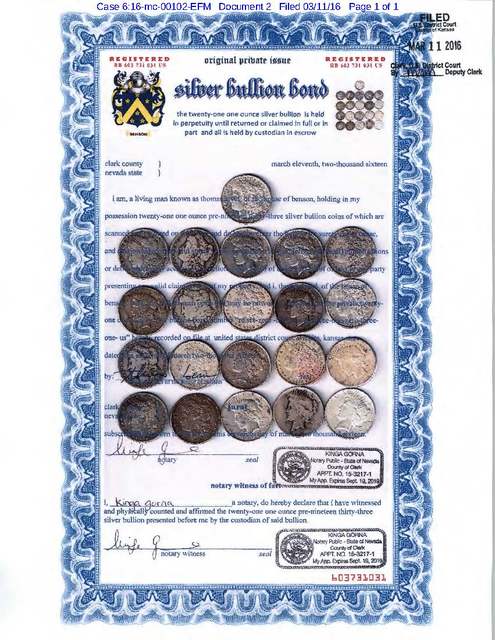

Meanwhile, after Benson sued Metro in June over the traffic stop – he alleged, among other things, kidnapping, and sought $12 million “payable in silver dollars” – attorneys said in court papers that he “espouses” sovereign beliefs. The lawsuit was poised to be dismissed, records show.

The Southern Poverty Law Center, which tracks U.S. hate groups, says sovereign citizens hold “truly bizarre, complex antigovernment beliefs.” Followers think they don’t have to pay taxes, can decide which laws to follow and are “clogging up the courts with indecipherable filings.”

When confronted, “many of them lash out in rage, frustration and, in the most extreme cases, acts of deadly violence,” usually against government officials, the center says.

But their “weapon of choice” is paper. According to the center, a traffic violation or pet licensing case can spark “dozens of court filings containing hundreds of pages of pseudo-legal nonsense.”

In Benson’s traffic case, he was ticketed and his car was towed after an officer found he didn’t have a license. But Benson claimed that he didn’t need one and that he was “traveling … in his private car, not for hire, not in commerce, not driving.”

According to the FBI, sovereigns sometimes write only in certain colors or include personal seals or red thumbprints. They also carry bogus driver’s licenses, commit mortgage fraud and use fake currency.

David Lopez, head of real estate fraud prosecution at the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office, said he deals with sovereigns “consistently.” They forge deeds, create bank accounts in multiple names, even hire prostitutes or homeless people to pose with fake IDs as deceased homeowners to give houses away, he said.

“We just get crazy stuff,” Lopez said.

LAWSUIT FOR THE HOUSE

On May 4, less than a week after the Catanias say they went back for their belongings, Benson filed a document with the Clark County Recorder’s Office: a lease for the home.

The custom-built property, 10280 W. La Mancha Ave., was bank-owned at the time. But according to the lease, the landlord was a person named Nana I Am and the tenant was The Batangyagit Foundation.

Benson and Nana also sued for the house the day the lease was filed. They sought $15 million, claimed that the foreclosure was illegal and said Nana was suing on behalf of Myles Catania.

The case was dismissed in September, and Catania told the Review-Journal that he had never heard of Thomas Benson, Nana I Am or the lawsuit.

Nana, who could not be reached for comment, is a mysterious figure who’s been accused of posing as a lawyer and of getting paid to help people stall foreclosures or evictions. Nana has filed dozens of lawsuits in recent years, often with people who lost their home to lenders, but he never seems to win. Most cases seemed to involve homes in Southern California, though he’s tied to at least a handful locally.

People arrested in May for squatting in a foreclosed home on Sierra Brook Court, a half-mile from the Catanias’ old house, claimed that Nana had given them the keys and coached them on what to say if police showed up, according to an arrest report. Nana also teamed with two of them to sue for the property, but police said they merely wanted to live for free in the two-story, 4,600-square-foot custom-built house with granite countertops and a dual staircase in the foyer.

When Benson was stopped by Metro, he says, he was driving to the Sierra Brook house.

Police say the homes are linked. And when the Review-Journal showed the Catanias the mug shots of some people arrested at Sierra Brook, the family said they were part of the group that had tossed their former home.

Marilyn Caston, a lawyer for the accused Sierra Brook squatters, said her clients mentioned Benson as being “affiliated with that elusive Nana I Am guy.”

Caston said she didn’t know whether her clients had met Benson or how they met Nana. But, she added, they would deny “any involvement with any other property.”

Benson has been linked to other Las Vegas homes.

Former owners of a house on Vista Linda Avenue in Summerlin said in court papers in 2014 that Benson had been “a co-resident” there with Perla Hernandez, who lost the property to foreclosure and had “no more than squatter’s rights” to it. They suspected he provided legal briefs and strategy that Hernandez used in court and claimed that he offered seminars and kits that helped people file “frivolous proceedings” to prevent evictions.

When the Review-Journal called a number listed in Hernandez’s court papers, a woman answered, but after a newspaper request to speak with Hernandez about her ties to Benson, the line went dead.

RAID BY AUTHORITIES

Benson was home with his wife and son and a house guest one morning when Las Vegas police and federal agents burst in. They broke down the front door, broke windows and pointed rifles at the group as they came downstairs. Benson wasn’t arrested, but police took his computers, phone, iPad and various papers.

That’s according to Benson, who described the June 28 raid in court papers. He included a copy of a search warrant that showed authorities were looking for information on mortgage fraud, sovereign citizen ideology and financial documents related to The Batangyagit Foundation. It also indicates they raided 1300 Mount Augusta Court, a home owned by Hernandez.

Benson has complained about the investigation into him, directing much of his ire at Detective Kenneth Mead of Metro’s Homeland Security Division, whom he sued as part of the traffic case.

He stated that Mead “seems to hold an extreme grudge” against him; that visitors could not come by to learn about his Javita Coffee product “for fear that they will all be investigated” by Mead; and that Mead and Metro “have as much authority to investigate me as WALMART SECURITY.”

Through a Metro spokesman, Mead declined to comment and said lawyers for Metro and the FBI would decline all interview requests as well.

BANK FORECLOSES

Bank of New York Mellon foreclosed on the Catanias’ house in November 2015, property records show. Myles’ wife, Carol, says the family reached a deal with attorneys to stay until June 1 but was evicted April 20. Officers had the locks changed and told the family they had 10 minutes to leave, the Catanias say.

An eviction was ordered April 13, court records show. A lawyer for the bank did not return a call seeking comment.

After scrambling to pack, the Catanias moved to Santa Fe Station. More than a week later, Myles got a voicemail from a man named Tom. Carol figured he was a lawyer for the bank but never learned who he was.

When the family arrived with U-Haul trucks, their belongings were strewn everywhere. The couple’s teenage daughter, Alexandria, got into a screaming match with a woman who wouldn’t say where her jewelry went. Tom also was at the house and talked about aliens and how Jesus had created the X-Men, she said.

Her sister Julie DiCurcio-Hornbuckle smashed furniture and other property with a sledgehammer after hearing that the strangers planned to sell at a swap meet what the family left behind.

Asked whether any of this made sense – if the family were locked out and strangers wanted to loot the place, why would Tom call? – they said no, it did not.

“When you’re in a hotel, so depressed and so upset, and your whole world’s upside down, you don’t stop to think about what’s rational,” DiCurcio-Hornbuckle said.

The bank sold the house in August for just over $1 million. Myles said he would move back if given the chance, though Alexandria isn’t sure. She loves the house, but it’s a “nightmare” to think about.

“It’s kind of scary that people are getting away with this at this point,” she said. “And I feel bad for people like us who are falling for it.”

Contact Review-Journal writer Eli Segall at (702) 383-0342. On Twitter at @eli_segall

RELATED

Several people are linked to purported Las Vegas sovereign citizen