Memories still vivid 50 years after Kennedy assassination

He was an ambitious young attorney then. He was 31. Harvard Law, only seven years removed.

He probably wore a tailored suit with a white shirt and a skinny tie, like Don Draper in “Mad Men.”

The year was 1963.

The ambitious young attorney remembers sitting in a conference room, in the U.S. Attorney’s office, in New York City. He was sitting among other ambitious attorneys. They were discussing a case. Probably a tax case. Probably an important tax case, because the door was closed.

It was a little after lunch on Nov. 22, 1963, when someone barged into the conference room and said JFK had been shot.

The ambitious young attorney was stunned. So were the other attorneys. They worked in John F. Kennedy’s administration. Robert Kennedy, the U.S. Attorney General, was their boss.

It has been 50 years since that initial report, and the follow-up reports, each more grave than the last.

Were it not for those shots in Dallas, the ambitious young attorney probably would be a retired federal tax judge now, and he wouldn’t be in Macau with Manny Pacquiao.

“It seems like it was just yesterday,” the fight promoter, Bob Arum, says before he leaves for China.

He’s 81 when he says this.

He’s 50 years removed from being an ambitious young attorney for the State Department. But you still can hear the melancholy in his voice.

■ ■ ■

On Nov. 22, 1963, the big kid from the Southern California suburbs was ready to hit someone in the high school playoffs. Ready to flatten somebody, like a pancake. By then, the big kid was on Notre Dame’s radar. Ara Parseghian wanted him. Everybody wanted him.

Being this was Southern California, you almost could hear Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys, with their striped shirts and their white pants, singing “Be True to Your School.” In perfect harmony, of course. It was all so innocent then.

The big kid was in Latin class on the third floor when he heard the terrible news. When you attended Catholic high school in those days, you went to Latin class. There was no way out of it. Not even if you could flatten guys sporting crew cuts like pancakes; not even if Ara Parseghian wanted you.

The big kid would play on a national championship team at Notre Dame and be named captain. He would be the second guy selected in the NFL Draft, behind O.J. Simpson. He would flatten guys for nine years in the NFL, play in eight Pro Bowls, become one of the premier offensive linemen of his generation.

A lot of that blends together for him now. It wasn’t at all like sitting in chapel at Loyola High, and praying for the president, and then hearing the terrible news on Nov. 22, 1963.

“That night, a Friday, the California Interscholastic Federation decided to continue with the playoffs, in which we faced Santa Monica High School,” said big George Kunz, now 66 and a practicing attorney in Las Vegas.

“The win was a bittersweet celebration after we lost an icon of hope.”

■ ■ ■

On Nov. 22, 1963, the fifth-graders in Mrs. Johnson’s class at Kenter Canyon Elementary in Los Angeles were watching a movie when one was summoned to the principal’s office. At first, he was nervous. It’s rarely good news when the principal wants to see you.

A clerk in the principal’s office said that President Kennedy had been killed and that he should be the one to tell Mrs. Johnson. Though he was only 11. So he told Mrs. Johnson sort of quietly, and she sort of quietly said he should return to his seat. And though he was only 11, the fifth-grader thought it strange that Mrs. Johnson should not tell the class about President Kennedy, though now he sees it differently.

Maybe Mrs. Johnson was only trying to keep order. Maybe the sudden death of a president who inspired so many, in such a ghastly fashion, was too much for a grown-up to comprehend.

A little while later, when all the school kids gathered in the commons to lower the flag, this same fifth-grader was asked to perform the task and to fold the flag military-style. And so he did, with help from his friend Tom Peyser, because it’s kind of tricky for a fifth-grader to fold a flag military-style.

That night, when he went home, the fifth-grader wanted to watch the Warriors play the Lakers on television. Instead, he watched Walter Cronkite. The TV newsman was somber, and so were the fifth-grader’s parents. The only words spoken that night were Walter Cronkite’s.

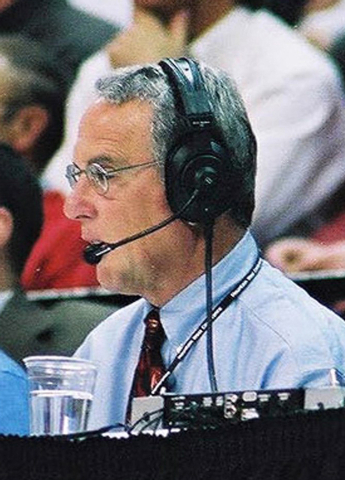

“The night was lonely, incredibly sad, empty and haunting,” recalled longtime Las Vegan and Oakland Athletics broadcaster Ken Korach, who said nothing after Nov. 22, 1963, seemed the same, even to a fifth-grader.

He said he often thinks of that day, and especially that night, and the feeling of loneliness, and how much he had been looking forward to watching the Warriors play the Lakers, even if it was in black-and-white.

■ ■ ■

On Nov. 22, 1963, the door to Sister Bridget’s first-grade classroom at St. Adalbert school just on the Indiana side of Chicago had been locked tight for recess. Out on Indianapolis Boulevard, you could hear the rumble of the big tractor-trailers; you could smell their exhaust.

Inside a darkened corridor, this kid with a big head, like Charlie Brown’s, and a French surname asked the classmate whose responsibility was locking the door for afternoon recess to open it again. The kid with the big head had left something inside. Probably baseball cards or a thermos with Roy Rogers’ picture on it.

The kid with the keys told the kid with the big head that he couldn’t unlock the door, because the sisters had said not to, and when you are in first grade and holding the keys, you do not want to upset the sisters and/or incur the wrath of our Lord, Jesus Christ.

But the kid with the big head persisted. He told the kid with the keys that if he unlocked the door, the sisters didn’t have to know, and that he also would share a secret about President Kennedy.

And that’s how I learned that JFK had been shot. From a kid with a big head named Dennis Frechette.

I remember being sad.

I had a scrapbook, containing baseball cards and autographs my dad had gotten for me and my brother at ballgames, and at bars, after the ballgames. The only pictures not of ballplayers in my scrapbook were of John Glenn, the astronaut, and this color postcard of President Kennedy.

And when I was 7, and Ken Hubbs, who played second base for the Cubs, died in a plane crash, I remember clipping the story out of the Sun-Times and pasting it into my scrapbook, right next to the color postcard of President Kennedy.

Las Vegas Review-Journal sports columnist Ron Kantowski can be reached at rkantowski@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0352. Follow him on Twitter: @ronkantowski.