America’s corrosive chemical legacy

I saw the mass of barren trees off the riverbank. What had been green was now black. Nothing alive was visible.

The year was 1969. I was in Vietnam as a military journalist. On that day I was doing a story for an Army magazine that would take me up the Saigon River in a patrol boat.

It was a day that served as my introduction to America’s chemical warfare program, then known as Operation Ranch Hand.

Men aboard the boat described how miles of forest and jungle were sprayed with deadly chemicals by American planes and helicopters. They laughed as they shared a twisting of the Smokey Bear motto, “Only we can prevent forests.”

I laughed, too. The chemicals certainly seemed to do what the men said they were designed to do — defoliate forest and jungle to deprive communist guerrillas of cover.

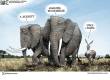

Today, as much of the world demands continuing forceful action against President Bashar Assad after his Syrian regime apparently unleashed a deadly chemical attack against other Syrians, I think about that day in Vietnam.

And I think about what I’ve subsequently learned about my country’s use of Agent Orange, a defoliant containing dioxin, one of the most toxic chemicals known to science. As it turned out, of course, it did far more than deprive the enemy of cover.

As world leaders debate how best to ensure that the direct use of chemical weapons against men, women and children be stopped, it may be instructive to examine what happened after the United States used them from 1961 to 1975 to kill vegetation in Vietnam, spraying nearly 20 million gallons of poison over 12 percent of the country, including 25 million acres of agricultural land.

That long ago action — those of us in the service were told it was harmless — continues to put the health of Vietnamese and Americans in peril. It has been linked by the National Academy of Sciences to 15 debilitating conditions, including several cancers, heart disease, spina bifida in children of veterans exposed to Agent Orange, and Parkinson’s disease.

There is no doubt that the government knew there were risks. A 1988 letter from James Clary, a former government scientist, to then-U.S. Sen. Tom Daschle, D-S.D., who was pushing legislation to aid veterans, reads in part: “When we initiated the herbicide program in 1960s, we were aware of the potential for damage due to dioxin contamination in the herbicides.”

Other scientists, however, say they had no idea that the potential for such widespread damage could become a reality.

Whether that’s true or not, taxpayers now shell out $1.52 billion dollars a year on the Agent Orange Compensation fund for U.S. veterans alone. Tens of thousands of American soldiers are in the pipeline to receive their justified compensation.

Pending legislation in Congress would provide billions more for compensation to the Vietnamese victims of Agent Orange and to the children of U.S. Vietnam veterans and Vietnamese-Americans who were born with deformities.

So many veterans are affected by the herbicide it’s not uncommon for Americans to know someone suffering from it. The VA says all 2.8 million Americans who served “boots on the ground” in Vietnam from 1962 to 1975 were exposed to Agent Orange. The VA recognizes 18 birth defects in the children of female veterans.

In June, Johnnette Fafard of Las Vegas described to the Las Vegas Review-Journal the battles her late husband, Raymond, had before receiving disability benefits for several conditions, including Parkinson’s disease linked to Agent Orange. When I was a public affairs officer with the Veterans Affairs Hospital in Houston in the 1990s, angry veterans I talked with were sure their conditions were caused by Agent Orange.

The agency that now takes months to act was even slower then in getting compensation to veterans.

According to experts, thousands of people, Vietnamese and Americans, have likely died from conditions brought on by Agent Orange. The Red Cross of Vietnam estimates 1 million Vietnamese are disabled or have health problems because of Agent Orange. The pictures Vietnamese leaders show of children they say were born with birth defects — 150,000 according to the government — are so horrific you quickly close your eyes.

Could America have done that?

American government officials quickly say the lack of validated data makes it difficult to estimate health effects. Yet it is also true that the U.S. government has agreed to spend millions of dollars to remove dioxin from contaminated soil in Vietnam.

An advertising slogan for a chemical company has long suggested there is better living through chemistry.

What we have learned from chemical warfare in Vietnam, however, is that there is also more dying, that it produces a war without end, stalking and claiming victims decades after the last spraying was done.

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.