Loneliest road in America suits Nevada residents just fine — PHOTOS

BAKER — In 1977, when U.S. Highway 50 was still the road less traveled, just another anonymous stretch of asphalt traversing the American West, Denys Koyle’s life took an unpredictable turn.

At age 28, she moved her young family from Huntington Beach, California, to this windblown frontier town on the state line between Nevada and Utah. She founded the Border Inn and scratched out a living tending to the occasional motorist who passed her ramshackle spread that baked under a relentless sun amid skittering lizards and prickly desert scrub brush.

To squeeze out the day’s last dollar, she would stand on the empty roadway well after dark, gazing up a 19-mile grade east into Utah: If she saw headlights descending, she’d stay open. Most times she closed.

That was before Highway 50 became famous.

It was an unlikely stroke of luck for Koyle and countless merchants along this meandering two-lane road that bisects Nevada’s midsection like an unadorned cowboy belt: In 1986 – three decades ago this year – the old highway became known as “The Loneliest Road in America.”

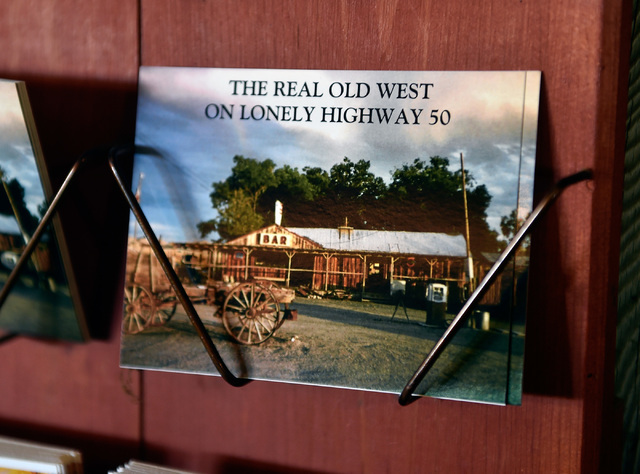

THE PHOTO

That July, a single photograph and caption in Life magazine assured readers that Highway 50 wasn’t just isolated, but downright lonely – something unpeopled and desolate, even apocalyptic.

“It’s totally empty,” one Automobile Club of America official said of a 287-mile stretch between Fernley and Ely. “There are no points of interest. We don’t recommend it. We warn all motorists not to drive there unless they’re confident of their survival skills.”

The stark image angered many central Nevadans trying to promote the historic wilds of the Silver State as a national tourist destination. Many wanted to sue Life magazine.

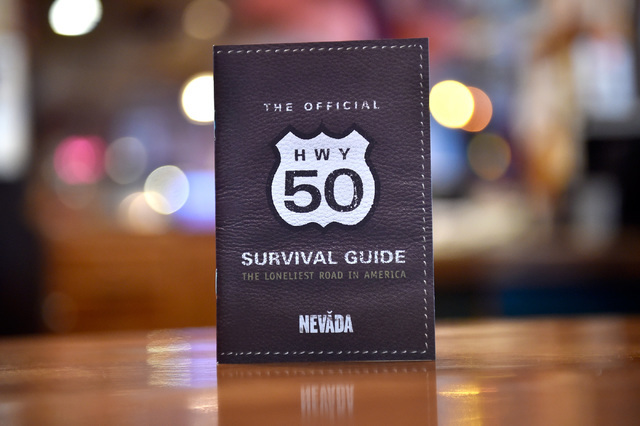

State tourism officials turned a tin-horned, would-be insult into pure gold: a campaign featuring state-issued passports along with a dare to try to survive a ramble down this lonesome highway.

Motorists soon flocked here from the United States, Europe and Asia, helping to revive the fortunes of struggling merchants such as Koyle.

“The ’90s were good,” said the 68-year-old, her hair now a flash of white. “It’s fun to go pay cash for a Lincoln Town Car.”

Still, decades later, many locals ask: Is Highway 50 really all that lonely?

The road’s path through central Nevada certainly was once dangerous, a route followed by overland stagecoaches dodging highway robbers. From 1860 to 1861, Pony Express riders galloped the route on a job so risky ads called for “Young, skinny, wiry fellows. Must be expert riders, willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred.”

The road later became part of the Lincoln Highway, one of the first transcontinental routes for automobiles in the United States. The U.S. 50 designation came in 1926.

Today, the artery crosses a dozen mountain ranges — with summits called Pancake, Pinto and Little Antelope — descending into vast desolate valleys where the asphalt runs ramrod straight for 25 miles, passing the bombed-out shells of old mines and the weed-strewn cemeteries where Nevada’s pioneers are buried.

Nowadays, lawless drivers often shoot game from the highway. On dirt roads that spiral off this way and that, cars kick up long, lazy trails of dust. One leads to the Hamilton ghost town, where enough silver was mined to help pay off some Civil War debt.

Along the way, there are scattered towns that stand as testimonies to the past, as well as the early culture that was carved out here. In Eureka, there’s an 1880 opera house that hosted plays, masquerade balls, dances and concerts. Ely’s Hotel Nevada was once the state’s tallest structure and the first with an elevator.

The road features lead-footed travelers on the highway marking the shortest distance from Denver to San Francisco, as well as locals in beaten-down old trucks hopscotching between towns at well under the speed limit. There are government biologists counting sage grouse, and the two cross-country cyclists from Norway who were greeted in one town with the offer of a free guest house and a refrigerator full of beer.

But Highway 50 is a fickle host.

Decades ago, before it’s “loneliest road” designation, bored wintertime drinkers at roadside bars wagered for drinks on how many vehicles would pass in an hour.

Those who guessed one or none usually won.

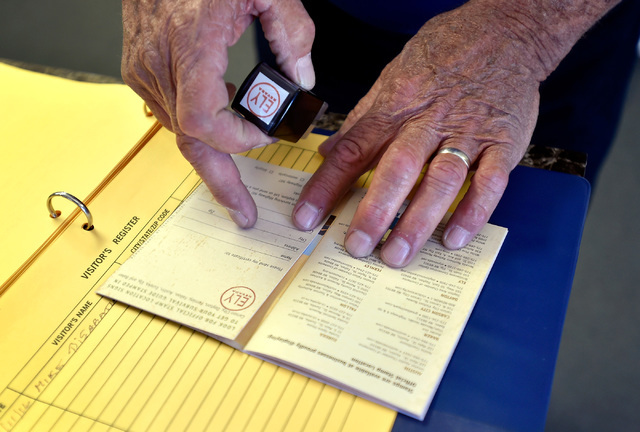

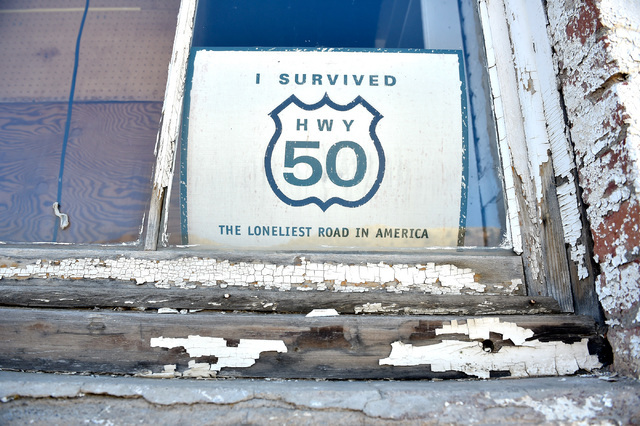

Now, summertime brings streams of tourists, whose stamped Highway 50 passports can earn them a certificate that proclaims, “I survived America’s loneliest road.”

In just two hours, Koyle recently stamped a dozen passports brandished by tough-looking bikers and carloads of suburban families.

“People stop in every little town and spend some money with their passports,” she said. “And rural Nevada needs all the help it can get.”

FROM INSULT TO ECONOMIC BOON

Ely resident Ferrel Hansen remembers the day the powerful local casino owner stormed into his office. Norm Goeringer was a spark plug of a man. And he was spitting mad.

He’d seen the magazine blurb about this loneliest road business, which he considered a slap in the face.

“Norm was a volatile but reasonable man,” recalled Hansen, then a local tourism official. “He wanted something done about it. And he wasn’t the only one.”

Hansen called state tourism officials. Rich Moreno, then a tourism public affairs officer, chased down the story. Turns out the Life magazine writer never even drove the road, but dialed up some unnamed AAA adviser in Denver or someplace, who said he’d heard of some road up in Nevada that was pretty darned lonely.

The agency later sent a letter to businesses along Highway 50, apologizing that it had done them a disservice. But the damage had been done.

“Ferrel wanted to sue Life magazine, or at least demand a retraction,” Moreno said. “And I’m thinking ‘Yeah, right.’ But then my boss said, ‘Well, what are we going to do?’ ”

Moreno’s solution was to goof on the whole episode. He helped create a program that used a mock Western tone to challenge motorists to try their luck on Highway 50.

Starting with a few hundred, the number of passports soared to the tens of thousands.

Ely area tourism director Ed Spear still shakes his head at the irony: “I guess if you throw enough crap at the wall, some of it’s going to stick.”

Spear, 67, is a lifelong Ely resident whose colorful conversations often meander like those of Hank Kimball, the county agriculture agent on the 1960s “Green Acres” TV show.

Under Spears’ direction, the community where “nobody lives inside the box” hosts such wacky events as chariot competitions and bathtub races at Cave Lake. Before that, folks set fires inside the tubs — salvaged from a local hotel — and shot cannons at them.

There are also fireworks shot from moving trains, an event Spear calls “the most fun you can have with your pants on.”

But the loneliest highway campaign isn’t without glitches. State tourism officials recently warned merchants to slow down handing out passports because there wasn’t enough funding to print more of them.

At the White Pine County tourism office, manager Wayne Cameron handed out a list of businesses where motorists could get their passports stamped. The problem: the word “loneliest” was spelled wrong.

Cameron sighed. “The state did that.”

Click image for larger version

NOT SO LONELY AFTER ALL

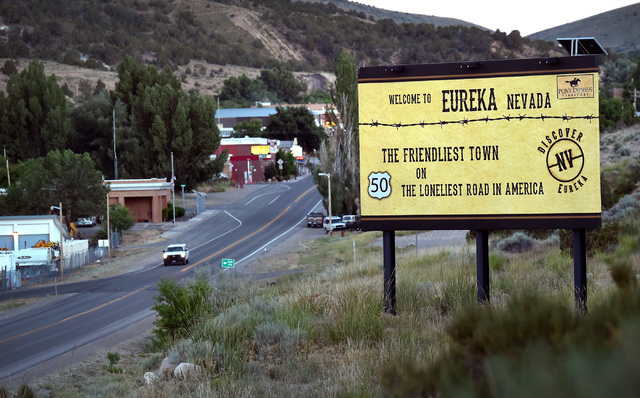

Leslie Oliver is serving lunch at the Pony Express Meats and Deli in Eureka, the place that bills itself as “the friendliest town on the loneliest road in America.”

She walks with a cast to help heal leg ligaments she tore in a hay-bailing mishap.

“I’ve never been lonely and I’ve lived here all my life,” she said.

That’s probably because of characters such as Tony Rowley.

At 64, Rowley features a wiry gray beard, greasy cap and bib overalls. He’s known as the mayor of this unincorporated town. There’s even a rib-eye steak sandwich named after him at the deli because he spends so much time jawboning there.

Rowley’s grandparents delivered mail to ranches all along Highway 50, in the beginning by horse-drawn carriage. His mother ran the local general store, selling old rocks and bottles, until she died a few years back.

“Lonely? Rowley huffed. “We all moved out here to get away from people.”

Down the road at Middlegate Station, a rustic bar and gas station on the site of an old Pony Express relay point, the sentiments are much the same.

Serving up drinks behind the bar, co-owner Russ Stevenson schools tourists on the curiosities along his stretch of Highway 50. There are the petroglyphs that marked ancient Native American deer kills, the quirky roadside volcanic-rock graffiti fashioned by passers-by, and the mysterious grave in the nearby salt flats that supposedly holds the bodies of two young girls who died of diphtheria on an 1850s wagon train; still dutifully kept up by an unknown benefactor.

But most people want to know about the shoe tree.

On a pair of nearby cottonwoods hangs hundreds of pairs of ballet shoes, red sneakers and screaming pink stilettos — an oddity that got its start in 1989 with a fight between newlyweds en route from Reno to Utah.

As Fredda Stevenson tells it, the couple spent all their money gambling and pitched a tent under the tree. The bride threatened to walk home. That’s when the groom threw her sandals on a branch.

He then drove down to Middlegate Station and told Stevenson the story over a beer.

“If you want to stay married, you’ve got to apologize,” she told him.

“But it was all her fault,” he protested.

“If you learn to say you’re sorry now, you’ll be happy the rest of your life,” she said.

The couple later returned to throw their baby’s shoes into the tree. Hundreds followed.

But in 2011, a liquor-fueled local cut down the tree to spite his soon-to-be ex wife, who had shoes hanging there. Fred and Russ hosted a memorial service attended by hundreds. Now more shoes have blossomed in a pair of nearby cottonwoods.

It’s just the latest strange story along America’s loneliest road. “You’re not going to see Nevada history driving Interstate 80,” Stevenson said. “On Highway 50 you can’t miss it.”

But, when it comes to sheer forlornness, Stevenson and others here point to forsaken U.S. Route 6 that runs 167 miles between Tonopah and Ely, where you can drive for hours and spot maybe a cow, or maybe not.

Now that, they say, is a lonely road.