Noted geologist recalls 1962’s ‘Big Dig’ at Tule Springs — VIDEO

TUCSON, Ariz. — Sometimes in science all you get is the chance to prove yourself wrong.

Geologist Vance Haynes expected to be part of a major discovery when he joined the Tule Springs archaeological expedition in the hills north of Las Vegas in September 1962.

Instead, the well-funded and closely watched dig unearthed only disappointment.

Although researchers collected fossils from mammoths, camels, bison and ground sloths, they never found what they were really looking for: proof of humans hunting ice age animals in North America almost 30,000 years ago, far earlier than previously thought.

As a result, some saw the project as “a horrendous boondoggle” at the time, Haynes said, but history would remember it for advancing the young science of radiocarbon dating and paving the way for the creation of Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monument in December 2014.

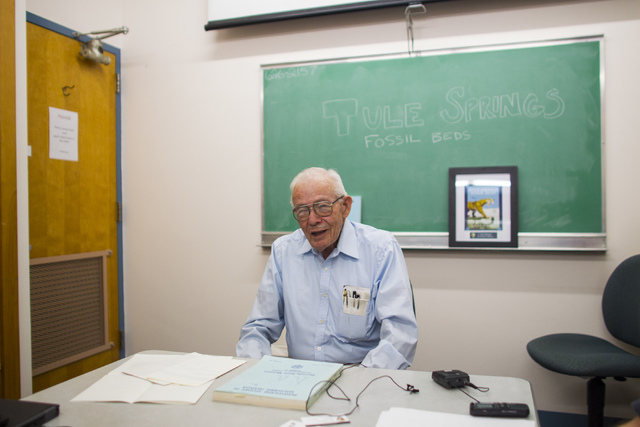

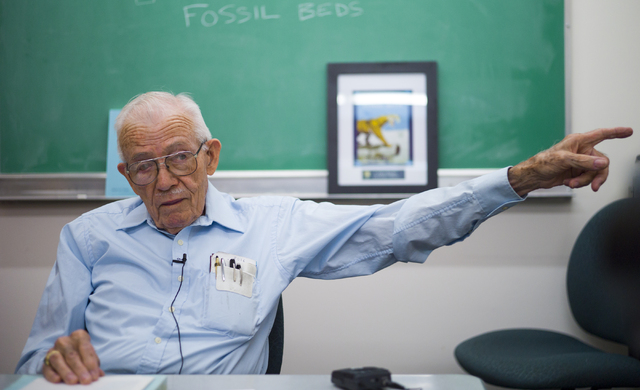

On Tuesday, a team from the National Park Service and the U.S. Geological Survey recorded an oral history with Haynes upstairs from his office at the University of Arizona, where the 88-year-old is a professor emeritus.

Park Service senior paleontologist Vincent Santucci conducted the interview. He said Haynes’ recollections will be preserved in the agency’s archives and undoubtedly featured some day in a display at the national monument.

“Being on that Tule Springs expedition was the best thing that ever happened to me,” Haynes said.

THE BIG DIG

He was a 34-year-old graduate student conducting field research in eastern New Mexico when he got a telegram asking if he wanted to be the geologist on a major excavation outside Las Vegas.

Haynes promptly dropped out of school to take the job.

“I had read everything that had been done about that location. I knew how important it was,” he said. “I had no hesitation.”

The “Big Dig,” as it later came to be known, was dreamed up by several prominent scientists who believed Tule Springs could hold answers about the arrival of humans in the Americas.

Previous work in the fossil-laden hills along the upper Las Vegas Wash yielded some tantalizing clues, including what appeared to be the remnants of an ancient cook fire strewn with bones from a now-extinct species of camel.

“It was at the forefront of people’s interest in archaeology in those days,” Haynes said.

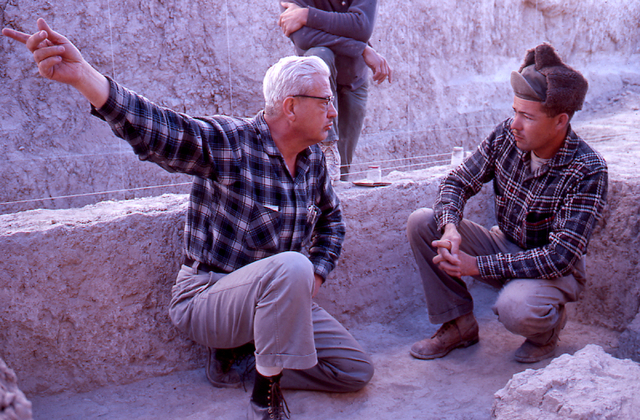

Researchers hoped to crack the case with heavy equipment, including what Haynes called “the biggest bulldozer in the world at the time.”

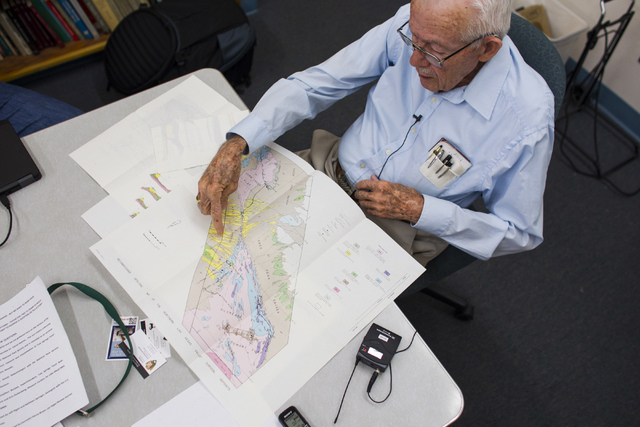

Under the direction of the Nevada State Museum — and with funding from the National Science Foundation — almost 2 miles of trenches were carved through the hills.

Plans also called for much of the surface to be scraped away throughout the dig site, but Haynes managed to persuade the project manager to leave those areas intact.

“These are like pages in the book of time,” he explained. “What’s above this stuff is just as important as what it’s in and what’s below it.”

One trench ended up far longer and deeper than the others because that’s where they would send the bulldozers and their union operators to keep them busy when there was no digging to be done elsewhere, Haynes said.

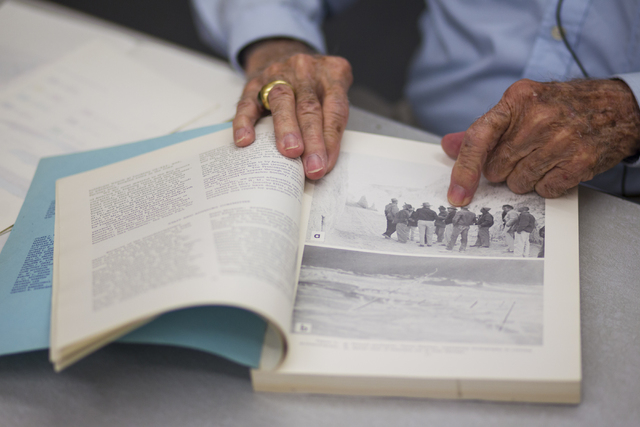

Old photos from the project show researchers working next to vertical walls of unsupported earth without a single hard hat in sight.

No archaeologist or workplace safety inspector would ever sign off on such a job today, Haynes said. “The use of heavy equipment is something that will never happen again, at least not in this country. It simply would not be acceptable in this day and age.”

CAMP LIFE

Paved streets and suburban neighborhoods now border parts of the almost-23,000-acre national monument, but at the time of the dig 10 miles of empty desert separated the site from the community’s northern edge.

On some nights, the researchers would climb the ridge next to their campsite and look out at the distant lights of Las Vegas.

“We were in the middle of nowhere,” Haynes said.

They named their camp after famed archaeologist M.R. Harrington, whose work at Tule Springs in the 1930s stirred further interest in the site.

For four months, Haynes and the rest of the 12-person crew lived in tents borrowed from the Boy Scouts as they collected artifacts in the triple-digit heat of early fall 1962 through the freezing temperatures of January 1963.

Haynes recalled one particularly nasty windstorm that knocked down a tent and carried off a colleague’s unfinished dissertation. “Pages of that draft went clear up into the Sheep Range,” he said.

But it wasn’t all bad. The team got weekends off, and “there was no rule against alcohol, so beer was prevalent,” Haynes said.

Then there was the time the geologist decided to entertain the crew by shooting off his replica of a mountain howitzer. The small cannon went off, but there was no immediate sign of its projectile, so Haynes figured it must have dropped harmlessly into the wash a short distance away. Then he saw a poof of dirt as the two-inch metal ball slammed into the distant mountainside.

“I baptized that shooting range out there,” he said. “That thing had gone over a mile.”

One of the project’s major benefactors was Joe Wells, a part owner of the Thunderbird Hotel who took an interest in the research and supplied the site with water and fuel. Wells also kept a standing reservation for the research team at a motel across from the Thunderbird so they would have a place to stay after a night on the town.

As a token of appreciation, the team presented Wells with a fossilized mammoth tooth at the end of the dig.

GIANTS OF SCIENCE

The camp had a generator to supply power and a cook to keep everyone fed. A trailer on site served as an office and guest quarters.

In the evenings, the researchers would gather in the mess tent to discuss the day’s findings.

Their work was reviewed throughout the project by an advisory committee of the nation’s top geologists, archaeologists and paleontologists, including Willard Libby, the father of radiocarbon dating and winner of the 1960 Nobel Prize in chemistry.

Libby devoted his lab at UCLA full time to analyzing samples from the dig. Someone from the lab made weekly visits to the site to collect material for carbon-14 dating. Haynes said they would get preliminary results back in as little as 48 hours, speedy even by today’s standards.

“Rubbing shoulders with all these people was a wonderful situation for me,” he said, even if what he found proved profoundly disappointing to some of them.

What looked like man-made hearths filled with charcoal turned out to be the bowls of ancient springs coated in oxidized plant material. What looked like tools shaped by human hands turned out to be bones cracked and polished by water and the elements.

“When I went out there, I was thoroughly convinced … the evidence was good,” Haynes said. “It’s very interesting what springs can do to make things look like artifacts.”

NEVER-ENDING QUESTIONS

Haynes would use what he learned at Tule Springs to earn his doctorate from the University of Arizona and launch a distinguished career that landed him in the National Academy of Sciences.

But some of the answers he sought during the Big Dig elude him to this day.

Despite a lifetime of study, Haynes still can’t point to definitive evidence that humans and ice age animals ever coexisted in what is now Southern Nevada.

And he said science still can’t adequately explain why most of the largest ice age animals on Earth suddenly died out about 11,000 years ago.

“It’s a real puzzlement,” he said.

That’s why Haynes is glad to see national monument protection for Tule Springs and its scientific treasures: because there is always more work to be done.

Haynes said he returned to the site of the Big Dig in 1984 when a conference brought him to Las Vegas. As he walked through one of the trenches, he plucked what looked like a piece of charcoal from the wall and took it with him.

He said he still has the specimen, and he hopes to run some tests on it someday.

“You know with any site you’re never satisfied,” the geologist said. “There are things I’d still like to do out there.”

Contact Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350. Find @RefriedBrean on Twitter.