DR. DESAI’S RISE AND FALL

A dozen palm trees sway gently in the breeze behind the Red Rock Country Club home of Dr. Dipak Desai. Tiny ripples move across the pond that sparkles even as the June sun begins to drop behind the mountains.

Two golfers, preparing to tee off on the 14th hole of the private course designed by the legendary Arnold Palmer, are clearly visible from the huge back window that dominates the physician's $3.4 million, 8,700-square-foot house on a hill.

But it's not a scene that the 58-year-old Desai would particularly relish, according to a longtime acquaintance.

"He doesn't like golf," said Kanti Patel, a 70-year-old retired engineer who has known Desai for 28 years. "He thinks it's a waste of time. I've never seen him play it or watch it. Basically all he's interested in is making money. He just lives on a golf course for the status.

"He's not that hard to figure out."

Until six months ago, few people outside the medical community cared what makes Desai tick. A man who examines polyps and hemorrhoids for a living generally doesn't generate much news.

That all changed in February, however, when health authorities advised thousands of patients of the gastroenterologist's Shadow Lane clinic to undergo testing for hepatitis and HIV. Authorities investigating a cluster of hepatitis C cases had observed clinic nurses reusing syringes in a manner that contaminated vials of medication and, they believe, infected patients. This dangerous practice, according to city investigators, was done at the direction of Desai and other administrators.

Desai's medical license has been suspended as authorities continue to investigate eight hepatitis C cases linked to his Shadow Lane and Burnham Avenue clinics.

Who is the man known in medical circles simply as "D?"

For this story, the Review-Journal spoke with dozens of Desai's associates. Most requested anonymity, saying they feared either retaliation or jeopardizing professional relationships with him.

Their assessments tend toward extremes.

Some believe him to be a dedicated physician, a decidedly spiritual man whose chief desire is to heal. They know him as a strict vegetarian who travels to his native India on religious pilgrimages where he joins millions of other Hindus in washing earthly sins away in the Ganges River.

Others see him as a blackmailer and a strong-arm tactician.

Little insight comes from Desai himself. Since February, he has refused media requests for interviews.

Phone calls go to voice mail. Knocks on the door are met with silence.

Richard Wright, Desai's criminal defense attorney and country club neighbor, says his client won't speak to reporters because he feels as though he's been "burned" by the media. How Desai has been "burned" Wright will not say.

ESCAPING 'HELL ON EARTH'

Desai's background did not assure the material success he has had in Las Vegas. He has told associates he came here with practically nothing, but now has a net worth of about $200 million.

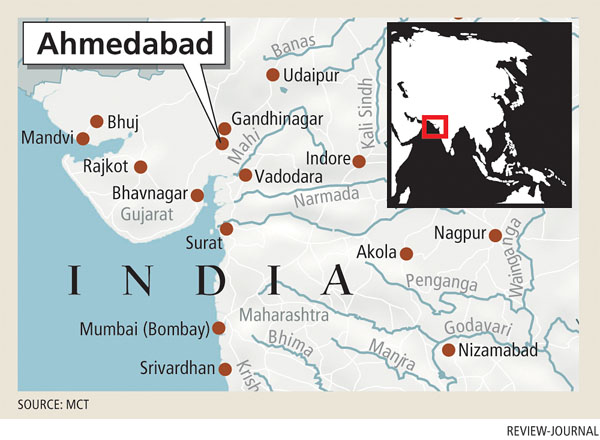

"You do have to remember that he came from a city in India, Ahmedabad, that is hell on earth," recalled a California real estate investor who said he attended college and medical school there at the same time as Desai. "Students studied hard to get the hell out of there so they could leave and make their fortune."

The businessman, an Indian who grew up in Africa, said when he and Desai attended Gujarat University in the late 1960s and early 1970s, there was no escaping the unsanitary conditions and corruption.

"You squatted over a hole in the ground when you had to go. There was no tissue so you used a wet hand to clean yourself," he said. "It was disgusting. In a 115-degree heat, you couldn't get away from the smell of human waste."

Bribery was a way of life.

"Just to get on the bus you had to bribe the conductor with extra rupees," he said. "There were always so many people waiting. It got so I'd climb in a window in the back to get on. ... You had to pay someone to get a job."

Desai has a formidable intelligence, his former classmate said. Raised in the Gujarati tongue of his native Indian state of Gujarat, Desai had to grasp scientific concepts at the same time he was learning the English language used at medical school.

Students there "really had to cram" if they wanted to immigrate and practice in the country they knew from Hollywood. "The medical students loved movies that showed America," he said.

Now a metropolitan area of almost 6 million, Ahmedabad was already teeming with 2 million people 40 years ago. Then, as now, it was the largest city in Gujarat. For most of the time that Desai was at the university, the city was also the state capital.

Nearly a quarter of the population, according to United Nations reports, lived in slums so filthy that people washed in streams where excrement and garbage were visible. There was no air-conditioning. Meanwhile, heavy industries and thousands of kerosene-fueled rickshaws belched black smoke into the air, the classmate said.

And without an infrastructure in place to deal with heavy rains, monsoons regularly left water four feet deep in much of the city.

"You had to wade through the water to get where you were going," the former classmate said. "You'd go to school with wet clothes. There would be snakes all over the place. The frogs would croak so loud you had a hard time studying."

What Desai's early life was like in Ahmedabad is unclear. The businessman said that he and Desai, who was a year ahead of him in school, spoke only a couple of times and never about Desai's personal life.

Patel, who grew up in another city in Gujarat and never knew Desai in India, said Desai seldom talked about his life there.

"He said his dad died early of a heart attack, at 44, I believe," Patel said. "That couldn't have been easy."

Patel said Desai, who was born in November 1949, did share that his family was of the Vaisya, or business and trader caste.

Though formally outlawed by the Indian government, the inherited class or caste structure that was long part of Hindu traditional society still lingers in the minds of some Indians, governing certain marriages and life opportunities, Patel said.

"I think he said his father was a businessman, but I don't know in what field," Patel said.

Desai was able to live at home rather than in college dorms, his former classmate said. He stressed that even if Desai lived in an area where sanitary conditions were the norm rather than the exception, Desai wouldn't have been able to escape the primitive side of Ahmedabad.

"Bugs literally became part of your meals," he said. "Cockroaches and flies were baked into your food. There was no way to avoid it. The government did nothing to kill them."

Although the businessman said the medical school was clean and academically rigorous, he said he has often wondered since the health care scandal erupted whether Desai ever escaped the filth and dishonesty of Ahmedabad.

"You may take the man out of Ahmedabad, but can you take all the Ahmedabad out of the man?" he said. "I didn't finish medical school because I couldn't stand the corruption (in the city) and lack of hygiene there."

OPPORTUNITY IN AMERICA

In the mid-1970s, Desai passed exams that allowed him to embark on a career in medicine in the United States.

After his arrival in the United States, he worked as a resident at Catholic Medical Center in New York.

In New York, according to Patel, Desai met his wife, also a native of India. Kusum Desai, a pulmonologist with whom Desai has three daughters, refused repeated requests for interviews.

Records show that during his time in New York, Desai obtained licenses allowing him to practice both there and in Maine.

By 1980, he was headed for Las Vegas.

"In his research, D saw that Las Vegas didn't have a lot of gastroenterologists," said Dr. Ivan Goldsmith, a Las Vegas internist who met Desai shortly after the Indian immigrant's arrival. "D's always been a good businessman. He would ask me to refer him patients."

If Desai and his wife had banked any money in New York, it wasn't evident upon their arrival in Las Vegas.

It was at the low-rent Sombrero Motel just south of Tropicana Avenue on Las Vegas Boulevard that Patel first met Desai. The doctor steered his Chrysler to the motel office through a parking lot dotted with beer cans.

Patel used the motel as temporary housing on weekends while working at the Nevada Test Site during the week. It wasn't unusual, he said, for management to call the cops to deal with rowdy patrons.

He said initially he was thrilled to be in the company of another immigrant from South Asia, particularly one who hailed from his home state of Gujarat. Yet Desai's boasts about his future wealth wore thin.

"Our conversations would always get around to how much money he was going to make in Las Vegas," Patel recalled. "Money, money, money. It was the most important thing to him."

Patel said the proprietor of the motel, Babu Naik, a man of Indian descent, didn't charge Indians to stay at the Sombrero, which was renamed the Pollyanna before being demolished five years ago.

"There was a kind of pipeline where Indians helped Indians who were coming to the United States," Patel said.

Naik, who now runs the Roulette Motel on Fremont Street, said he is proud that Desai became successful in Las Vegas.

He said once investigations into the hepatitis crisis are concluded, he's sure people will see that Desai's only intention is to help people.

"That's all he's ever wanted to do," Naik said, noting he still sees Desai at religious gatherings at the Hindu temple in Summerlin. "He's a very good man."

The Desais lived only a few weeks at the motel before moving into an apartment, Patel said.

According to Patel, a South Asian doctor steered Desai to 700 Shadow Lane, a medical building near Valley Hospital. That building would remain at the core of Desai's practice until February of this year.

His Gastroenterology Center of Nevada, a consulting practice with 14 physicians, was there until authorities shut it down. So was the Endoscopy Center of Southern Nevada, the busy clinic where the outbreak was discovered.

IMMIGRANT DOCTOR ON THE RISE

Soon after Desai's arrival in 1980 he became tight with Dr. Elias Ghanem, Goldsmith said. Ghanem was a Lebanese immigrant whose career had taken off in Las Vegas a decade earlier when he treated Elvis Presley.

Ghanem, who died in 2001, also treated Liberace and Michael Jackson, earning the moniker "physician to the stars." Among his other patients: then-Gov. Bob Miller and President Clinton's mother, Virginia Kelly.

"D figured out how to get close to the right people," Goldsmith said.

Ghanem's lucrative medical clinics, the Las Vegas Medical Centers, catered to Culinary union workers in the hotel-casinos.

"Ghanem became extremely powerful in the medical community because he was the man referring all those Culinary patients to specialists," Goldsmith said. "He had a huge impact on the livelihoods of physicians."

Ghanem, an active fundraiser for politicians on both sides of the aisle, began to refer patients who needed gastroenterological services to Desai, according to Goldsmith.

With his medical practice taking off, Desai became a homeowner and took his first turn as a land speculator.

Records show that his first home, a 3,200-square-foot house near Rancho Drive and Sahara Avenue, was purchased for just over $127,000 in 1981.

That same year, documents reveal, Desai and his wife joined with Dr. V.A. Ram and his wife to buy a 121/2-acre plot for $322,850 at Rancho and Lone Mountain Road. That parcel, plus an adjacent 11-acre parcel the foursome bought later for $1 million, would earn more than $4 million in profits by the time the last piece was sold in 2004.

A physician who invested in land deals with Desai said the Indian immigrant told him that since 1981, he had also purchased land in Arizona, California and on the East Coast.

"He has gotten many physicians in land deals with him," the doctor said. "Desai told me the land deals have helped his personal worth go over $200 million. Other physicians appreciate his reaching out to them. He has a tremendous mind for business. He's not only helped physicians that way, but he's also helped set up their practices. The only thing he asks in return is that they refer patients to him.

"That makes sense."

All of his wheeling and dealing might have taken a toll. In the mid-1980s, Desai -- seemingly the picture of good health at a slim and trim 5 foot 6 and 150 pounds -- had a heart attack, Patel said.

"He almost died," he said.

The first hint of trouble in Desai's medical practice also surfaced in the 1980s. Judy Witman, one of his medical technicians, said she became concerned about the physician's work, even as his reputation grew and his practice became busier and busier.

"Everybody thought he was this great physician," she said in a phone interview from her Pennsylvania home. "But he wouldn't allow us to properly clean the scopes (used in colonoscopies) because he was in a hurry to get patients through to make more money. He was so cheap. There was always blood and stool on them" after they were washed. "It was disgusting."

Witman, who now works for a Pennsylvania hospital, said she quit her job at Desai's clinic after a few months and notified the Nevada State Board of Medical Examiners about Desai's behavior in 1989.

She said she never received a return call.

"This terrible thing that happened might not have if they had listened to me," she said.

There is no record of the complaint. Tony Clark, executive director of the medical board, said the board keeps no record of complaints that aren't acted upon.

Two years later, registered nurse Wendy McMurray, who headed the endoscopy center at Valley Hospital, became concerned about Desai for a different reason.

Desai tried to get Dr. Julian Lopez "thrown off the staff," McMurray recalled. "He wanted me to say that the new guy was incompetent. He didn't want the competition. I couldn't do that. Lopez was a much better doctor than Desai."

The misgivings that Witman and McMurray had about Desai never reached Gov. Miller, who would appoint Desai to the Nevada State Board of Medical Examiners.

"I only heard good things about him," Miller said. "He seemed so professional."

Miller said he met Desai after becoming governor in 1989, but he can't remember exactly when.

The Democratic governor had been referred to Desai by Ghanem, the governor's personal physician.

That referral would radically change Desai's life.

Desai's removal of a polyp for Miller, a routine procedure, impressed the governor.

"He (Desai) was so charismatic and caring," Miller said. "There certainly was no indication of his being anything other than a good physician. His practice was growing dramatically."

In 1992, Desai followed Ghanem's lead and provided free medical care to striking Frontier Hotel workers who had no medical insurance. Ghanem, whose managed care company had a contract to provide medical care to 85,000 Culinary and Bartenders union members and their dependents, said it was important for union members to know the medical community supported them.

"I wasn't born rich, and sometimes you have to give something back to the society in which you live," Desai told the Review-Journal at the time.

Desai, one of 700 specialists who received referrals from Ghanem's company, acknowledged in the Review-Journal interview there was a business component to the free care.

In 1993, Miller appointed Desai to the medical board.

Miller stressed that he talked to other physicians about Desai's suitability for the board.

He said he can't remember, however, who the doctors were.

But Lopez, a physician who admits to an extreme dislike for Desai, said the appointment had to be "strictly political."

"He (Desai) was always bragging about doing two-minute colonoscopies, procedures that bring in money but are bad for patients," Lopez said. "Other doctors knew there was no way you can detect problems patients may have in two-minute scopes. It wouldn't be wrong to say it takes at least 10 times that long."

TAKING CHARGE ON THE BOARD

No one, according to longtime Nevada physicians, has ever taken better advantage of an appointment to the medical board than Desai. Reappointed by Miller in 1997, Desai didn't leave the board until 2001.

"It gave him the opportunity to do basically what he wanted to enrich himself," Lopez said.

He became the medical director for gastroenterology at University Medical Center in 1994 and chief of internal medicine at Lake Mead Hospital (now North Vista Hospital) the same year. He also would become Valley Hospital's director of gastroenterology and get the opportunity to teach at the University of Nevada School of Medicine. He no longer has those positions.

According to Goldsmith, Desai at a party in the late 1990s publicly expressed his gratitude to Ghanem, who survived an FBI investigation into his own clinic's billing practices and accusations that he was one of the doctors who provided drugs that contributed to Elvis' death.

"He stood up and said (to Ghanem), 'Thank you for showing me how to use power,''' Goldsmith recalled. "It was from Ghanem that I'm sure he learned it was smart to both contribute and hold fundraisers for politicians."

Goldsmith said it didn't take long for him to learn how Desai could use the power of his board position.

"I admit, I once let a physician's assistant work in my office before I received the necessary paperwork from the state," Goldsmith said. "It was just a bureaucratic thing. The PA had passed all the necessary tests, but I still shouldn't have done it. Somehow D found out about it. He hadn't liked the fact I was referring patients to Lopez, so he was looking at me.

"He (Desai) was on the investigative committee of the board at the time. He told me he could go after my license if he wanted to. But he said if I started referring my patients to him instead of Lopez, he'd forget about it. I had no choice but to start referring my patients to him. I'd call that blackmail."

A former member of the medical board who served at the same time as Desai now admits he became disturbed with how his colleague appeared to be using his position. Yet he said there was nothing he could do about it.

Desai's former board colleague said he learned from other doctors that they were contacted by Desai and assured that if they referred patients to him they would never have to worry about being the subjects of any disciplinary board action.

"I asked them why they didn't file a complaint, and they said there would be no proof of what he was doing," the physician said. "There was nothing I could do."

Another physician, Dr. Charles Cohan, who now lives in Pennsylvania, also had concerns about Desai in the 1990s. He filed three complaints with state officials regarding what he felt were deceptive advertising practices and billing irregularities.

The complaints went nowhere, he said, which he blames on Desai's influence with regulatory officials. But the last straw for him came in a 1999 phone call from an unidentified caller, a year after he filed a complaint with the attorney general's office.

It was a threatening message directed at his family, he said. Soon afterward, he left the state.

BEFORE THE FALL

The new millennium appeared to have special promise for Desai. Once again he showed his flair for land deals.

In 2000 he bought a 4.8-acre plot of land near U.S. Highway 95 and Kyle Canyon Road for $300,000. Five years later he sold it for $3.2 million.

He was proud that his older daughters were flourishing, an associate said. One is a physician, the other a lawyer.

He was especially pleased with the role he played in the opening of the Hindu Temple in Summerlin in 2001, noted Swadeep Nigam, the Clark County Republican Party treasurer.

"He gave the largest donation ($250,000), and many people are thankful for that, but some people think he tries to determine what happens at the temple," said Nigam, who created a Web site for South Asians called vegasdesi.com. "We even have people who write in about that."

Gopala Krishna, the temple's priest, said Desai is a religious man who tries only to use his medical knowledge to help others, and that his wife is active in children's programs at the temple.

"Dr. Desai cares so much about people," he said recently as he sat in the temple, where his daughter translated for him. "He is a very good man, and the people can't believe the man they know is the man they are reading about in the newspaper and see on TV."

An officer in 17 Nevada-based corporations, Desai was among the founders and organizing board members of the Bank of George. He also became a founding director of the Nevada Mutual Insurance Co., a liability insurer that covered his Endoscopy Center of Southern Nevada. Desai has resigned from both institutions.

His contribution to the Keep Our Doctors in Nevada lobbying effort -- the $25,000 donation was the largest in the state -- paid off as voters agreed with physicians that it should be much more difficult for individuals to sue doctors for malpractice.

Newly elected-Gov. Jim Gibbons named Desai to his transition team, which Nigam described as a nod to Desai's political donations, fundraising expertise and political savvy.

Like Ghanem, his mentor, Desai was respected by lawmakers and he would donate to opponents in the same race.

"Politicians would take his calls," Nigam said.

Desai's Gastroenterology Center of Nevada gave to both Gibbons and failed Democratic candidate Jim Gibson before the last gubernatorial election. He donated to Rep. Shelley Berkley, D-Nev., and Republican Don Chairez when they vied for a congressional seat in 1998.

He enjoyed holding fundraisers and parties.

"He used to seat doctors who didn't like each other at the same table," a physician said. "He enjoyed watching them argue."

In 2004, Desai moved from his home in the Canyon Gate Country Club to his palatial estate at the Red Rock Country Club.

His youngest daughter got a position as an intern in Sen. Harry's Reid's office, a position she resigned from in February.

Desai's gastroenterology practice, already the largest in Southern Nevada with three clinics, was poised to become even larger.

"He planned on opening a clinic in office space near the new Centennial Hills hospital," one physician said.

And positive news even came out of a stroke Desai had recently suffered.

"He bounced back from it so fast," said one physician. "He didn't seem to suffer any aftereffects."

But on Feb. 27, Desai's seemingly endless rise came to a halt.

Public health officials announced that more than 40,000 of Desai's patients had to be tested for blood-borne diseases, the largest notification of its kind in U.S. history.

Desai and his medical team became the subject of local, state and federal criminal investigations.

Lawyers representing thousands of former patients filed civil lawsuits, which could tie up the courts for years. Associates of Desai say that almost immediately, he began to spend considerable time with his own attorneys planning a defense strategy, a practice he continues today.

The story of a doctor allegedly putting profits before patient safety drew international attention, with the Times of India referring to Desai as "Dr. Greed."

In an effort to try to turn his fortunes around, Desai engaged in the Hindu religious rite of yagna on at least three occasions, according to two of his associates. During that ritual worship, in which a priest invokes various gods as he chants mantras for hours, the individual before him prays for help and makes offerings into a sacred fire.

More publicly, Desai responded to the uproar in Southern Nevada by publishing a full-page open letter in the Review-Journal.

He expressed sympathy "for the fear and uncertainty that naturally arises from the situation."

And he made a promise: "For those who are uninsured, a foundation is being set up to cover the cost associated with the tests. You will learn more about this in the days to come."

More than 100 days have passed. No further word has emerged about the foundation.

Review-Journal writer Brian Haynes contributed to this report. Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim @reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.

Watch the slideshow