College simulation event stimulates charter school students

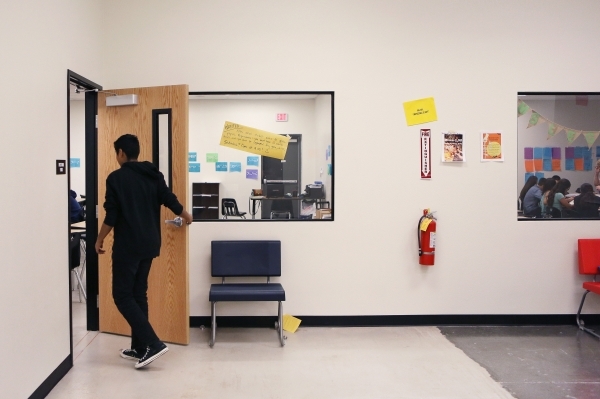

For two days last week, an unorthodox college campus opened its doors in northeast Las Vegas and welcomed an inaugural class of exclusively middle and high school students.

In the old Carpenters Union training hall on Bonanza Road, teachers and staff at the Equipo Academy charter school suspended their schedules for eighth- through 10th-graders and assumed the roles of college professors.

Students, most of them teenagers, sat through a range of university-level courses that included introduction to engineering, presidential election politics and race and diversity. In between their two-hour classes, the students had to choose between joining a study group, playing video games in a recreation center or visiting the campus "quad" at the nearby Mike Morgan Park.

"I absolutely love this," said sophomore Claudia Montes, 17. "You have a lot more freedom, but you have to teach yourself how to use that wisely."

"It's hard, but college seems to me mostly about what you put into it," she added.

Time management and personal responsibility were two of the main lessons that Equipo Academy founder and principal Ben Salkowe hoped students would take from the new school's first college simulation event on Tuesday and Wednesday.

Salkowe modeled Equipo Academy, which opened in August, after charter schools in New York and Texas that aim to promote 100 percent of their graduates to a college or university. The problem, however, is how to guarantee that the students actually succeed and complete a degree program once they move away from home and lose the immediate support of teachers, friends and family.

"We're not just teaching our students math, reading and writing, and how to do them at a college level," Salkowe said.

"We're actually teaching the skills that they'll need to be successful in college," he said. "We don't want to just get every kid a college acceptance letter. We actually want to get them a college diploma."

With that goal in mind, faculty members over the summer brainstormed an immersive experience that replicated nearly every aspect of life at a university.

One teacher designed an online registration form, which capped total enrollment in each class and, much like a university, benefited students who registered early.

Students initially needed to complete an application, including the essay portion, to join the simulation. About 20 students missed a strict deadline and, also like at a university, did not receive an acceptance letter.

"We tried to be almost robotic," Salkowe said. "We tell them, 'We love you, but realistically you wouldn't be in college if you missed that deadline.'"

On Wednesday, ninth-grader Damaris Lemus stood in front of her peers during a simulated college of education class and presented a lesson she developed to teach elementary students how to write in cursive.

Students in the engineering course defended their designs for a parking garage, while another classroom broke into groups to discuss social inequality.

With two additional simulations planned for next semester, teachers throughout the events will observe which students seem to be more responsible compared to those who may need more support.

Ultimately, Salkowe plans to share the classroom-level data with the school's governing board and community donors, hoping to persuade them to provide more resources so he can prepare each student to get into and through college.

"It's kind of a new idea for a public school, because you're basically investing money into people who are not necessarily supporting your day-to-day students but supporting your graduates," Salkowe said.

"But we didn't want this to be a crap shoot," he added. "We didn't want to throw everything at these kids and just hope they're successful in college."

Montes already feels prepared to attend her dream school, the University of Southern California, where the 17-year-old wants to study education before one day replacing Salkowe as principal of Equipo Academy.

She recalled her time in middle school, where she said the principal called her "the devil's child" and suspended her for behavioral problems.

"I didn't have a reason to be in school. I didn't really have a goal," Montes said. "I didn't know there was something else beyond school or, I guess, only thought college was for privileged people. I've never had anyone care for me before here. Now I want to be a teacher. I want to come back here and give the same opportunity to other kids who don't think they have it."

Contact Neal Morton at nmorton@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0279. Find him on Twitter: @nealtmorton