Lawmakers avoid showdown over Clark County school system breakup plan

Lawmakers have avoided a showdown of sorts that threatened to stall a plan to reorganize the Clark County School District by agreeing to a last-minute list of compromises forged to build greater support.

Among the winners: Parents who demanded more representation on campus-level teams that will guide the hiring of principals and budget, instructional and staffing decisions at each school.

Residents from Henderson and Moapa Valley, who long have clamored for a clean split from the nation’s fifth-largest school system, also lobbied for a more direct role in the reorganized district. They got it and now will help select area supervisors and receive regular reports from them.

But, as expected, not everyone’s happy with the final plan and a revised set of regulations that would set the reorganization in place by August 2017. Critics include the Clark County School Board, minority rights advocates, school support staff and more.

They will have a chance to air their grievances Tuesday, when an advisory committee charged with approving a final plan considers the regulations for approval.

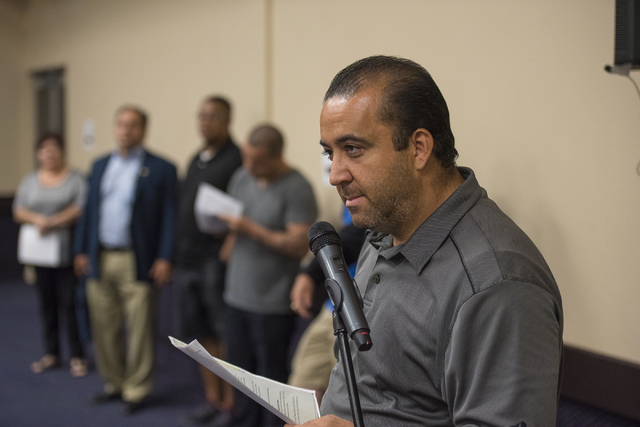

“The reality is I have to count votes,” said Sen. Michael Roberson, R-Henderson.

He chairs both the advisory committee and the Legislative Commission, a panel of 12 lawmakers that also must grant its approval before the plan becomes law.

He chairs both the advisory committee and the Legislative Commission, a panel of 12 lawmakers that also must grant its approval before the plan becomes law.

“That’s six Republicans and six Democrats,” Roberson said Thursday. “So for me to be able to get this reorganization plan, which is more than just one issue … I have to keep this bipartisan.”

The advisory committee meets 9 a.m. at the Grant Sawyer state office building, 555 E. Washington Avenue, to vote on the final set of regulations.

QUESTIONS LINGER

On July 1, the advisory committee gave its tentative blessing to a plan that would strip power away from central administration and grant more autonomy, in return for greater accountability, to individual schools.

Draft regulations since then have grown from eight to 24 pages, reflecting how successfully — or not — various interest groups have persuaded lawmakers to include their wish list in the final product.

The compromises include keeping some services, such as equity and diversity training and English language learner support, with central administration. One citizen, Roberson said, also persuaded him to add a nonvoting member to the campus-level teams as a representative of the wider school community.

Many of the regulatory changes were secured by the loudest voices at a series of town halls held over the last three weeks to gather public feedback on the plan.

At those meetings, Sylvia Lazos, policy director of the education reform group Educate Nevada Now, said she heard “continued confusion by parents still trying to understand the process and what I’ll call palpable fear” from school employees.

“Given that, we are where we are, and I think that we have to move forward,” Lazos said Thursday at a Clark County School Board meeting.

"We think this is the best thing for families, the best thing for students"

- Break Free CCSD#CCSDReorg #nved #nvleg #ccsd— Nevada Succeeds (@NevadaSucceeds) August 12, 2016

Also at that meeting, school support workers railed against their decreased representation on campus-level teams and continued to press for protections to prevent principals from outsourcing jobs.

Meanwhile, civil rights activists worry that the achievement gaps between white students and their peers from other socioeconomic backgrounds will widen.

“I’d like to see that change, so that those kids are protected as well,” said Yvette Williams, chair of the Clark County Black Caucus.

“That would be my main concern with this plan,” she added. “Our students, again, are being stuffed up in the attic where no one can see them.”

Education policy wonks, some of whom have the power to derail the plan, also remained concerned about its real-world impact. They question whether the regulations will codify existing policies that subsidize teacher salaries at schools in affluent neighborhoods by diverting money meant to help at-risk students.

“Everyone I’ve heard from is concerned that the financial model for staffing perpetuates inequity, runs counter to the goal of student-weighted funding, and limits ability to measure” return on investment, said Victor Wakefield, a member of the State Board of Education.

“I’m not sure how to solve this, but the conversation seems worth having.”

PERPETUAL INEQUITY

Last week, Wakefield and fellow board members Felicia Ortiz and Mark Newburn — all three represent Southern Nevada — met with the Las Vegas Review-Journal to share their reservations over endorsing the regulations. The full board meets Sept. 1 to approve or reject them.

Their concern centers on how the district calculates teacher salaries for every school.

Under the rules, schools would pay a district-wide average for the cost of salaries plus benefits of all 18,000-plus teachers. That’s regardless if the actual salaries paid at a given campus are above or below that rate.

“Think of it this way,” Ortiz said. “Let’s say, for example, we all use NV Energy to get our electricity. What if NV Energy charged us the average that everybody used?

“We will be billed the average, even though my house is 1,200 square feet and (another) house is 5,000 square feet,” she said.

In practice, the board members fear, the average salary model would transfer money away from schools in low-income and high-minority areas. Long-term substitutes and beginning teachers, who come with low salaries, often fill classrooms at such schools.

State resources meant to support students in those schools, however, would flow instead to Henderson, Summerlin and wealthy communities, where principals easily recruit highly paid and more experienced educators.

“The kids (attending schools) that we’re staffing with the least experienced teachers, these are the kids who get the least support at home,” Newburn said. “These are the kids where a string of really effective teachers means the difference between graduating or not.”

It appears Roberson shares their concerns, as the updated rules include language that in July 2019 would trigger a review of the average salary model’s impact on equity in the classroom.

Roberson acknowledged that other issues may arise if the plan is approved and implemented over the next year, and he has committed the advisory committee to staying involved in that process for at least two years.

“We have statutory authority, at a minimum, to the beginning of the 2018-19 school year,” Roberson said.

“The work doesn’t stop here,” he added.

Contact Neal Morton at nmorton@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0279. Find him on Twitter: @nealtmorton