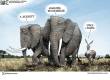

Enforcement no success story

Since its creation in 2003, Immigration and Customs Enforcement has had a hard time pleasing anybody.

Some critics accuse the agency of token enforcement. Others see its goals carried out only in fits and bursts. A vocal minority decries ICE's entire effort as a sham.

Mark Krikorian, executive director of the Center for Immigration Studies, a group that supports tighter controls on immigration, said enforcement has become "theater, a show."

In Southern Nevada, the federal government's track record of nabbing illegal immigrants almost has been preordained to fail.

Nevada is estimated by the Department of Homeland Security to have the 10th largest population of illegal immigrants in the country. But the number of full-time ICE employees in the state recently ranked 30th.

The Las Vegas area is not among 61 places in the country with a permanent team that chases a fast-growing group of illegal immigrants: foreign nationals who have ignored deportation orders. Such a team is expected to be in place by the end of this year.

Nevada also has had a dramatic drop in referrals for federal criminal prosecutions. Such charges are seen as a deterrent to illegal entry because of the stiff prison sentences they carry. The decrease in Nevada bucks a nationwide trend.

Workplace enforcement has been spotty in this region, which is estimated to have at least 100,000 illegal workers. These efforts have focused on a handful of job sites deemed by the government as important to national security, not on sectors that employ the most undocumented workers.

As the country debates the immigration law of tomorrow, the federal government is mired in an uphill battle to nab the illegal immigrants of today.

Despite a record number of deportations last year nationally and a stated goal of the "removal of all removable aliens," ICE has been able to expel only a small percentage of illegal immigrants.

The story of immigration enforcement here and elsewhere is one of limited successes and predictable failures, and of pledges to do better as the national debate creeps forward.

ICE, the successor agency to the Immigration and Naturalization Service, is using its limited resources in nonborder states to focus on illegal immigrants who have criminal records, have ignored orders to leave the country or both.

The agency, one of 22 within the Department of Homeland Security, has given both groups official-sounding names: "criminal aliens" and "immigration fugitives," also known as "alien absconders."

ICE spokeswoman Virginia Kice said her agency has a well-defined wish list.

"I would certainly acknowledge we prioritize cases that deal with national security or public safety, but anybody who's in this country illegally is subject to arrest," she said.

But immigration enforcement is only one of ICE's pursuits. Others include investigating drug smuggling, Internet crimes and gang activity, a broad mandate for an agency that got $4.7 billion this fiscal year.

The Homeland Security Department estimates that Nevada has as many as 240,000 illegal immigrants, but this state is treated like all other nonborder states when it comes to enforcement, Kice said.

In overall staffing, Nevada's ICE office lags behind other states, according to an analysis of data from the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University, a privately funded organization that collects data from government agencies.

Similar problems also have plagued Customs and Border Protection, the Homeland Security Department's other lead investigative agency. The agency recently beefed up its presence at McCarran International Airport out of fear the airport had become a hub for immigrant smuggling.

In 2003, Nebraska and Missouri each had more than four times the number of full-time ICE employees Nevada had, though the illegal populations of those states are dwarfed by Nevada's.

Nebraska and Missouri are home to meat processing plants that have been raided by the federal government.

ICE does not comment on staffing issues.

Only about 2,000 ICE agents are assigned to the interior of the country, a fraction of the number assigned to the border, according to the Center for Immigration Studies.

Former Immigration and Naturalization Service agent Mike Cutler told a congressional committee in 2005 that interior and border enforcement deserve the same attention: "We need to have legs of equal length. ... They need to be coordinated and understand they all work in the same program to accomplish a common goal."

On occasion, ICE has sent agents from other states to help round up people with outstanding deportation orders from an immigration judge.

In the spring of 2006, ICE officers from three states conducted a six-day operation that netted 179 illegal immigrants in Las Vegas. Another 100 fugitives were picked up in a sweep here in August.

But a March report by the inspector general of the Homeland Security Department concluded that insufficient detention space, limitations of an immigration database and inadequate working space have hampered ICE's efforts nationwide.

KNOCKS ON THE DOOR

On a pre-dawn April morning, a group of ICE agents set out to find three immigration fugitives here. On occasion, these house calls lead to "collateral arrests" of others on the premises. It was the type of targeted sweep the agency conducts a few times a month in the absence of a permanent fugitive operations team.

Marco Flores-Cortez, 28, a Filipino national, was in the shower when his stepfather opened the door of his Henderson home to agents.

Ten minutes later, Cortez was dressed and on his way to a temporary detention center at ICE's local headquarters near Pecos and Sunset roads.

Cortez, who lost his status as a legal permanent resident after pleading guilty in state court in 1999 to attempted grand larceny, had avoided immigration authorities for about four years.

During that time, he worked at a fast food restaurant and an Internet cafe and cared part-time for his 8-year-old daughter, who was born two years after Cortez arrived in the United States.

ICE agents earlier this day had booked two fugitives from Peru and Mexico at their homes. They and Cortez were fingerprinted, processed and told they could take up to 40 pounds of luggage and $10,000 with them on their return trips home.

The agents went three-for-three that day, but the government's track record of capturing immigration fugitives has not kept pace with the annual increase in their numbers.

Typically, an immigrant with questionable legal status will be taken before a judge in a civil court administered by the Department of Justice. In some cases, the immigrant will be ordered to leave the country. Some obey, but many don't. Those who don't or who don't appear for hearings are considered immigration fugitives.

ICE estimates there are about 630,000 such fugitives, about 5 percent of the entire illegal immigrant population of 12 million. The number of fugitives has increased at an annual rate of up to 87,000 nationally, but fewer than 18,000 fugitives were removed last year, creating a backlog.

ICE reports that the size of the backlog has decreased this year, and the agency expects to remove twice as many fugitives as last year.

ICE did not make available local data on the number of fugitive arrests.

Last year, the federal immigration court in Las Vegas handled 3,138 cases, 500 fewer than the year before, according to the Justice Department's Executive Office of Immigration Review.

During the April raids, Frank Galvan, the chief of ICE's local detention and removal operations, gave a sober view of his agency's performance: "We haven't been able to keep up."

Galvan hopes that will change with additional staffing and the creation of a permanent fugitive operations team in Las Vegas later this year.

Said Galvan: "We'll be able to do sweeps daily, not just once or twice per month."

LITTLE PRAISE FOR AGENCY

ICE is viewed warily by advocates on both sides of the immigration divide.

"It's encouraging to see any enforcement of the immigration laws because they were essentially abandoned for years," Krikorian said. "Token enforcement is a fair description of what is happening now."

Angela Kelley, deputy director of the National Immigration Forum, puts it another way.

"They're (ICE) clearly trying to step up their efforts so they can't be accused of failing to enforce the law," said Kelley, whose group favors fewer restrictions on immigration.

Impartial observers view ICE with a degree of sympathy.

John Booth, a political science professor at the University of North Texas, said the agency has a "virtually impossible job."

"They're underresourced and overmandated," he said. "Everything they do is going to irritate somebody."

ICE has been enforcing laws that many, including Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff, believe need to be changed.

In an April speech, Chertoff spoke of the importance of border and interior enforcement, explaining that "being tough is part of the commitment to the American people to prove to them that this time we are really serious."

Chertoff continued, "We also have to be smart. And that's where I think that the work that we're doing now to try to produce immigration reform is very important."

Chertoff lobbied unsuccessfully for a sweeping immigration reform bill that died in the Senate last week. He said in a June speech that the bill would bring "a change in enforcement posture" more focused on determining who's legal than who's illegal.

THINKING OF COMING BACK

The other main thrust of ICE's enforcement efforts centers on felons such as Jose Fierro-Calderon.

Calderon, 42, a Mexican national, was serving six years on drug charges in the Southern Desert Correctional Center when he was told to leave. Less than 24 hours later, he was on a government jet en route home.

Calderon was among the first batch of 45 illegal immigrants serving time in Nevada who were turned over to ICE in April after getting sentence reductions, an attempt to help ease overcrowding at state prisons.

Asked about his future, Calderon thought for a moment.

"The goal for everybody is to come back," he said in nearly flawless English. "I'm thinking of coming back, but not right away."

"If immigration got me, they could give me time. That's my big concern."

If Calderon returns and is caught, he could be charged federally with illegal re-entry, which is used by federal prosecutors to discourage deported immigrants from trying to cross the border again.

Depending on a defendant's criminal past, the charge can carry a prison sentence of up to 10 years.

In 2003, about 21,000 people nationwide were prosecuted on immigration charges, including illegal re-entry, according to TRAC, the records clearinghouse. Last year, that number jumped to more than 36,000.

In border states, immigration-related criminal prosecutions have skyrocketed. Federal prosecutors in Arizona last year filed 9,565 cases, four times as many cases as in 2003.

The data show an opposite trend in Nevada, where between 2003 and 2006, prosecutions fell from 240 to 112. Immigration prosecutions in neighboring Utah jumped from 233 to 283.

Steven W. Myhre, acting U.S. Attorney in Nevada, points the finger at ICE and other Department of Homeland Security agencies for making fewer referrals for prosecution.

"The policy of this Office has been to prosecute all immigration violations ... where there is sufficient evidence to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that a crime occurred," Myhre said in an e-mailed statement.

Russ Knocke, a spokesman for the Homeland Security Department, attributes fewer prosecutions in some places to the type of defendants being charged.

"We're not doing nickel-and-dime cases," Knocke said. "We do not want your immigration enforcement agents wasting their precious time tracking down landscapers and maids. We want them to focus on high-impact cases," he said.

Knocke cites examples dealing with human smuggling and national security. But that strategy has not been on display in Nevada, where such cases have been few and far between.

Of the 112 cases prosecuted by the U.S. attorney's office here last year, three dealt with human smuggling, all stemming from activities in Northern Nevada. None of the immigration cases appeared to deal with national security.

'WHAT DO YOU NEED?'

Most illegal immigrants come to this country to work.

Some go to the Bonanza Indoor Swap Meet on Eastern and Bonanza roads to make that possible.

Visitors to the market are still unbuckling their seat belts when document peddlers descend.

The questions, in Spanish, come rapid-fire: "You need a green card? Social Security number? What do you need?"

In 2002, ICE arrested more than a dozen members of a group that manufactured and sold bogus documents. But arrests have hardly made a dent in the practice.

Such papers allow scores of undocumented workers to hold down jobs in the region, but workplace raids in Southern Nevada largely have been limited to sites the government classifies as critical infrastructure: McCarran International Airport, Creech Air Force Base and Hoover Dam.

Resources are again an issue, according to a report last year by the U.S. Congressional Research Service: "In the aftermath of the 2001 terrorist attacks, resources available for work site enforcement further dwindled, as interior enforcement increasingly focused on national security investigations."

Largely absent have been enforcement sweeps among Southern Nevada's largest employers of undocumented workers, the hospitality and construction industries.

Several raids took place earlier this year: at the Harley-Davidson Cafe, the Red, White and Blue at Mandalay Bay, and ESPN Zone, area restaurants whose cleaning staffs were provided by a company ICE investigated for harboring illegal immigrants. The sweeps led to several arrests.

Stephen Usiak, the director of investigations for ICE in Las Vegas, doesn't think that many illegal immigrants work along the Strip.

"The gaming industry to a degree will police itself because you need a sheriff's card to work there," he said. "I'm not going to say the gaming industry as a whole is 100 percent clean, but it's close."

Still, Usiak admits that it is difficult to keep up with the document counterfeiters:

"Every time we go one step further to make something more fraud-proof, they see it as a challenge for them to catch up."

HERE TO STAY?

Jose Cruces was among a group of 20 Mexicans who trudged five days through the Arizona desert last year to get to the United States illegally.

Since coming to Las Vegas a couple months later, the 33-year-old Cruces has earned as much as $500 per week as a day laborer, hiding in plain sight from authorities.

A clean record and a little luck might be enough to keep Cruces out of trouble as he stands on a street corner each morning, looking for work.

Usiak's Office of Investigations handles community complaints against companies and laborers such as Cruces, who have become an increasingly visible presence here.

But complaints against them have gone unaddressed, some local residents said. The most critical claim Las Vegas has become a "sanctuary city" for illegal immigrants.

On its Web site, the Las Vegas-based group Americans4America outs companies it alleges hire undocumented workers.

"We are losing what our country is made of," said Kricket Telfer, the group's founder. "Is our government trying to make us a Third World country?"

The government's top security official doesn't think so.

Chertoff, in a December speech, said laws need to be enforced with economic realities in mind:

"Only a temporary worker program will give us the ability to deal with that tremendous economic draw which has time and again over the years defeated all the enforcement measures that the government has placed on the border to try to get security for this country."

ILLEGAL IMMIGRATION: Counting The CostMore News Stories

Guatemalan goes it alone before judge By ALAN MAIMON REVIEW-JOURNAL Alberto Lenus-Garza stands alone in his fight against deportation. Convicted of assault in a 2001 incident on a Los Angeles-area soccer field, Garza is trying to persuade an immigration judge from the Department of Justice to let him stay in the United States. Such proceedings are civil, not criminal, and Garza has no right to a jury trial or a government-paid attorney. Garza, 28, a native of Guatemala, legally entered the country on a tourist visa in 2000. The sales assistant at a local sneaker store is representing himself in court: "I make $8.25 an hour. I can't afford lawyer fees." Garza recently took a second job at a Las Vegas fitness center to help support his mother and 10-year-old brother. He is seeking asylum to stay in the United States and is claiming that he has been threatened by people in his home country for taking part in anti-government protests while a university student. At a May hearing, Immigration Judge Ronald Mullins grew impatient with Garza after he said he wanted to go to Canada if deported. "You can only select Canada if you're from Canada. You can only select Mexico if you're from Mexico," Mullins explained. The judge continued: "I take this very seriously, but I question at some point if you take it seriously." Garza said that he plans to better prepare for his next hearing before Mullins in July. "I don't want to go back to Guatemala," he said. "I just have to convince the judge to let me stay."