John C. Mowbray

John Code Mowbray once found himself the military governor of a province of Korea, recently liberated from the Japanese.

In the first growing season, he forced peasant farmers to withhold from market for storage enough rice to keep themselves until another harvest. The farmers gave it up only reluctantly, for any rice "stored" by the Japanese had never been returned.

That winter, another province, where nobody had mandated food storage, was running out. One of Maj. Mowbray's superiors, a colonel, ordered rice to be seized from Mowbray's province and redistributed to the other.

"I can't do that," Mowbray protested. "I got this rice at the point of a bayonet with my solemn promise it would be returned to them. My people will starve."

The colonel was unmoved.

Mowbray was even prepared to defy orders and hide the rice.

But he went over the colonel's head to a general, arguing the military government ought to keep its promise.

Mowbray prevailed, but the experience left a bitter memory. He saw the farmers at the mercy of a military with godlike powers. The farmers never got to present their own arguments, never chose him to present them, could not have appealed had they lost.

Mowbray spent the rest of his life, 25 years of it on the Nevada Supreme Court, seeing that any citizen of Nevada could have his day in court. Along the way, he helped build Southern Nevada's social safety net of privately funded charities and its best-known parochial school.

Mowbray was born Sept. 20, 1918, in Bradford, Ill. A good student, he had the bad luck to graduate from high school in mid-Depression, and there was no money for college.

"Let me try to put myself through," he told his father. "I'll never know if I could have done it, unless I try." And he did, waiting tables and doing odd jobs while earning a teaching credential, then teaching school while studying for a law degree.

World War II intervened; he enlisted in the Army Air Corps and became a pilot, but was tapped to run a photo reconnaissance school in the United States, and never saw combat.

After post-war service in Korea he went to Notre Dame law school. Students there weren't permitted automobiles, and he was hitchhiking the day Kathlyn "Kax" Hammes gave him a ride. They later married and moved to Las Vegas in 1949.

Kax' father, Romy Hammes of Kankakee, Ill., was an American success story so spectacular that Life magazine did articles on him -- twice -- in 1938 and 1946.

Hammes started his career as an auto mechanic, didn't like it, and in 1917 -- at age 17 -- got himself transferred to a clerical position with the opportunity to sell Model-T Fords in the evenings. By 1926 he was named the best Ford salesman in the United States; in 1929 he bought the first of five Ford dealerships he would own.

Hammes' other ventures included real estate development in Illinois, Indiana, Hawaii, New Jersey -- and Las Vegas. One of the Mowbrays' first roles was developing the Marycrest neighborhood, which generally surrounds Bishop Gorman High School and St. Anne's Elementary School off Maryland Parkway.

Both schools were part of the neighborhood plan. Las Vegas attorney John Hammes Mowbray researched the role of his parents and grandparents in Gorman's founding for a 40th anniversary program at the school. "As my grandparents financial success grew following World War II, and the need for more churches and schools became apparent with the birth of the 'baby boomer' generation, my grandparents answered the call," he wrote.

Gorman became the preferred high school not only for Las Vegas' Catholic youth but also for the elite of other faiths.

Mowbray also helped found the Home of the Good Shepherd, a charity that served as a sort of halfway house for girls with discipline problems. He was active in Knights of Columbus and in Catholic Community Services.

Meanwhile, Mowbray had begun his legal career as one of two deputies in the Clark County district attorney's office.

Decades later, he still carried haunting memories of children harmed by adults, and the helplessness of being unable to prosecute successfully because Nevada lacked a child abuse law. In one case, a Searchlight child was being treated badly. "His teacher told us the child came in with his face green from being beaten," Mowbray recalled years later. The boy was forced to do adult chores, said Mowbray, and was severely punished when they proved beyond his ability.

Mowbray said he warned the judge that if the boy were left in that environment, he would not survive.

"Sure enough, in about six months, this boy was trying to start a fire with kerosene and was burned all over his body." The boy died.

Mowbray lobbied the Nevada Legislature and won the state's first child abuse law.

In 1959, Gov. Grant Sawyer tapped Mowbray to fill a vacancy on the bench of Clark County District Court. At the time, there was such a backlog the court actually refused to accept new civil cases. Mowbray cleared the logjam by devising a "master calendar system," which his son describes as "similar to having airplanes stacked up in a holding pattern over an airport." Since many cases are settled or dropped on the day of trial, the plaintiffs and lawyers in several tentatively scheduled cases would wait in the courthouse hallways in case a courtroom would be vacated by settlement.

Mowbray was also dissatisfied with the system used to provide lawyers for indigent defendants. William Morse, who began practicing law here in 1950, remembers that each judge had a calendar call on Fridays. "If they needed an appointment for an indigent, the judge would look out over the courtroom and pick somebody and say, `You're it.' If it was a capital case they usually appointed two.

"You did this basically for free. I remember that George Dickerson spent literally years defending one guy, and I think he got $500."

Mowbray applied to the Ford Foundation for a grant to set up a public defender system, and appointed young Richard Bryan, who would eventually become a U.S. Senator, as the first public defender.

The judge spent many of his weekends as one of the adult escorts for Boy Scout Troop 108, sponsored by St. Anne's Catholic Church. "We would camp at Willow Beach, Red Rock, Mount Charleston," said son John.

"I didn't realize at the time how hard it was for him to do this, but now I know he was doing it at the same time he was clearing up that huge backlog of cases and establishing the master calendar system. Sometimes we would be gathered on Friday night, and a bailiff would show up and say, `He's still on the bench but he's still coming.' And he always did show up, coming straight from court."

He remembers an incident when he, as a patrol leader, chewed out a patrol member in front of the others. "My dad came over and said, `You better never do that again! You have something to say to a guy, you tell him in private.' And he said that about four times," just to let John the Younger know how it felt to be corrected in front of his peers.

John H. and his brothers Romy and Jerry all became Eagle Scouts. The judge received the Silver Beaver Award. He also served as president of City of Hope and the National Conference of Christians and Jews, and as a board member of the local YMCA. He was intensely interested in American history and was a national trustee of the Sons of the American Revolution and the Freedoms Foundation.

In 1967 the Nevada Supreme Court was expanded from three to five members, and Gov. Paul Laxalt appointed not only a fellow Republican, Cameron Batjer, but Mowbray, a Democrat.

At the time, Laxalt said he chose men with conservative legal philosophies.

One of the few justices of his time who had previously been a trial judge, Mowbray was reluctant to second-guess juries. He would rarely vote to overturn death sentences, and often railed against delays in execution.

Justice Cliff Young, who served many years with him, said Mowbray rarely let a technicality overturn a just verdict. Once, Young related, an attorney wanted to argue such a point. Mowbray responded, "Counselor, you know what that man did? He raped that little 2-year-old! Why, he oughta be taken out and shot! But let's give him a fair hearing first."

In 1991, he was one of the majority who ruled that even though Nevada companies might fire employees "at will," whatever disciplinary procedures they announced in employee handbooks were binding on employers as well.

He was largely responsible for the change in rules permitting Nevada judges to allow news photography and television coverage in trial courtrooms.

The years Mowbray served saw bitter factionalism in the court, mostly about the autocratic style of sometime Chief Justice E.M. "Al" Gunderson. Mowbray usually disagreed with Gunderson.

About 1989, Mowbray had eye surgery for glaucoma, and by 1991 he no longer felt competent to drive his own car. His vision deteriorated to almost complete blindness. Even so, he accepted the post of chief justice for 1991 and 1992, but delegated liaison with the Legislature, one of the job's important duties, to Young. When he was assigned to write a legal opinion, assistants who were also attorneys looked up citations and wrote the draft under his supervision and oral editing.

Other justices began to question whether he was still carrying his load. Yet they tolerated his handicaps until November 1991, when Mowbray proposed a rule limiting the length of time a justice could retain a case without rendering an opinion, and announced the proposal without consulting other justices.

Three of the other four justices -- Charles Springer, Thomas Steffen and Robert Rose -- hit the ceiling. Steffen said, "This was in effect a press release designed to kick off his campaign for re-election."

The three justices responded by stripping him of his personal staff and urging him to retire. The dispute turned bitter, with Mowbray revealing telephone records that tended to confirm reports E.M. "Al" Gunderson, though retired, continued to influence court business. Justices Steffen, Springer and Rose retaliated by auditing Mowbray's telephone records, showing thousands of dollars worth of calls that had nothing to do with court business.

Mowbray's main defense was that while he made some personal calls, he never charged the state per diem for the two weeks a year the court met in Las Vegas, where he maintained a home. Also, he noted, the phones in his office were accessible to many people, and some of the calls -- such as one to a gynecologist -- were likely made by somebody else.

An investigation by the attorney general indicated no criminal wrongdoing but recommended Mowbray repay $2,805 for some of the calls. Mowbray did.

Pressure to resign made Mowbray determined to seek re-election. His sonswanted him to begin a peaceful retirement. He had planned to file for re-election on the last possible day; his son Jerry spent the day driving around with his father, purposely dawdling until he missed the deadline.

When his term expired at the end of 1992, Mowbray retired to Las Vegas, where he died on March 5, 1997. Not long before his death, his son John got him to speak, however obliquely, about the fights he had weathered on the Supreme Court.

"As we came to the end of it," recalled John, "he said, `Don't ever be afraid to do the right thing. I always tried to do that, and no matter how many cases I decided, I've always been able to go to sleep at night.' "

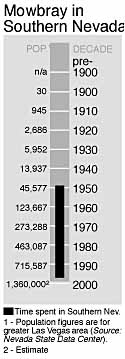

Part III: A City In Full