Salt used to remove road ice on Mount Charleston may kill trees, advocates say

The ice melted months ago from the roads on Mount Charleston, but its impact is easy to see.

High in Kyle and Lee canyons, brown patches of dead and dying trees bracket the highways, some of them 100-foot Ponderosa pines older than the Declaration of Independence.

It isn’t the cold that’s killing the trees. It’s the salt that gets scattered on the roads each winter to melt away snow and ice.

Workers from Clark County and the Nevada Department of Transportation apply roughly 300 tons of salt-based de-icing agent annually to the roads and parking lots within the popular Spring Mountains National Recreation Area.

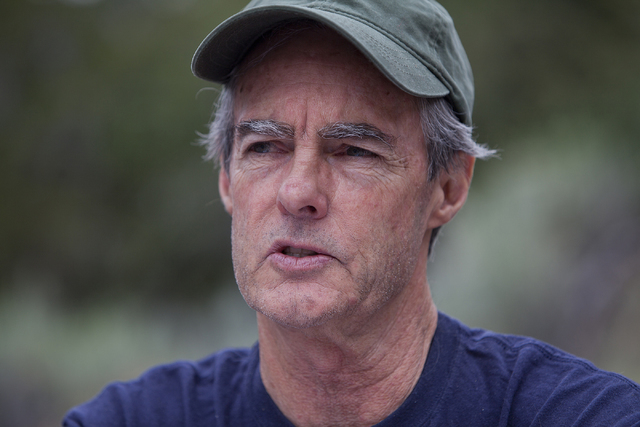

UNLV researcher Dale Devitt said those chemicals inevitably wash off the pavement and into the root zones of plants that are poorly adapted to process salts. If the sodium chloride doesn’t kill them outright, it weakens the trees, leaving them vulnerable to drought, disease and infestation by bark beetles.

Devitt collected soil samples and published a paper on the impact of de-icing salts on Mount Charleston in 2014.

“We had places where the salinity was higher than what you’d find in seawater,” the soil and water scientist said. “That shouldn’t happen.”

Devitt is part of a growing chorus of researchers and mountain residents who want forest managers and transportation officials to find a new way to keep the roads clear, one that doesn’t hurt the environment. At the very least, Devitt would like to see additional testing of ice treatments that are less likely to foul groundwater and damage trees.

“Everyone uses sodium chloride, of course, because it’s cheap,” he said, but there’s another cost to consider: the sudden loss of Ponderosa pines that have towered over the landscape for hundreds of years.

“They were saplings long before any white men climbed up into those mountains. It begs the question: What’s the value of a tree?” Devitt said. “If you discount the value of a single tree, pretty soon you’re devaluing the entire forest.”

CHAIN SAWS AND ICE SLICER

But the answer might not be as simple as spending more money on a new mix of de-icing materials.

Kevin Killian is the state transportation department’s highway maintenance supervisor for the Mount Charleston area. For decades, he said, icy roads on the mountain were treated with a mixture of sand and salt, leaving behind a layer of grit and dust that eventually ran afoul of air quality rules.

Killian said they solved that problem about four years ago by switching to a product called Ice Slicer, which dissolves completely in water and doesn’t need to be mixed with sand or cinders. It’s still mostly sodium chloride, but it works so well they don’t have to use nearly as much of it. He said “a quart pickle jar” of the stuff will melt as much ice as a 5-gallon bucket of the old salt-sand mixture.

They’ve tried other products, including a magnesium sulfate mix Devitt recommended in his study, but Killian said they haven’t found anything that works as efficiently in the unique conditions on Mount Charleston.

“If anybody comes up with one, we’d be willing to try it. We’re absolutely willing to try anything anyone’s willing to bring to us,” he said.

Killian isn’t convinced that salt is what’s killing the trees anyway. He’s not even convinced that trees are dying at a significantly higher rate than before.

He said road crews used to routinely remove between 20 and 50 dead trees a year from the highway right-of-way, but the U.S. Forest Service put a stop to the practice about a decade ago. The brown trees that line the roadways today are the result of that 10-year lull in cutting, Killian said.

Others insist there has been an increase in dead trees, a dramatic one that began right around the time NDOT switched to its new de-icing agent.

“What we saw in 2012 was something we had never seen before,” said John Guyon, a Forest Service plant pathologist who has conducted yearly assessments of the Spring Mountains since the early 1990s. “There was a very definite increase in tree damage. We saw a lot of freshly salt-damaged trees.”

Guyon can’t say for sure if Ice Slicer is to blame, but what he has documented is consistent with exposure to salt both in the soil and in “spray drift” stirred up by passing vehicles.

“Direct causality is really hard to prove in biology,” he said. What he can say with certainty is that roadside trees on Mount Charleston experienced a “pulse in mortality” in 2012 and 2013, and the damage is ongoing.

Much of that dead timber is now being cut down down as part of a massive hazard tree removal project, which is exactly what it sounds like.

Last year, Guyon helped identify at least 700 dead, dying or beetle-ridden trees at risk of falling across roadways, onto structures or power lines on the mountain. State forestry and transportation crews began cutting down those trees and hauling them away in the fall.

Killian said about 150 trees have been removed so far. He expects the job to take another three years or so and wind up costing about $750,000.

The work has been on hold since late April to allow for bird migration and nesting in the area. The chain saws should start back up in a month or two, once biologists give the all-clear.

PERILS OF ROADSIDE LIFE

The project seems like a tragic waste to mountain resident Tom Padden. As far as he is concerned, those trees didn’t have to die.

“It’s so obvious that it’s the salt that’s doing it,” he said. “Salt should never have been used in this environment at all. Ever. This isn’t the same as a commuter route out on the East Coast.”

Padden has spent most of his life on Mount Charleston, where he lives with his 96-year-old father in the same house the old man built in 1956 using some of the last boards produced by the sawmill there.

“If you wanted to live up here back then, you had to have 4-wheel drive and shovel a pile of snow. You had to adapt to the mountain, because there wasn’t much chance of the mountain adapting to you,” he said.

Today, though, the area serves as an overburdened playground, crowded on winter weekends with visitors who expect clear roads and easy access to the ski hills and snow play areas high in the canyons, Padden said. People flock to enjoy the unique and fragile ecosystem, never realizing they are contributing to its destruction.

“I’ve seen the transition from what it was before to what it is now, almost all the result of human influence, unfortunately,” he said. “The mountain is in a very precarious state.”

Forester Eric Roussel from the Nevada Division of Forestry said short of closing the highways for good and tearing out the pavement, there’s not much to be done to prevent tree mortality along the mountain’s transportation corridors.

“Salt is part of the problem; it’s not the entire problem,” Roussel said. Drought, disease, bark beetles and other unhealthy forest conditions are also taking a toll, as are the inherent hardships of living right next to a road.

Even if the use of salt were halted tomorrow, he said, “we’d still see trees dying on Mount Charleston.”

It’s sad to see majestic old pines turn brown and die, said Roussel’s boss, John Christopherson, natural resource program manager for the state forestry division, but the safety of people on the road will always trump the health of the forest right next to it.

“There are some beautiful old-growth trees up there within the (road’s) zone of influence,” Christopherson said. “Whether it’s salt or road oil or exhaust, trees along the roadside suffer a lot of indignities that trees out in the forest do not.”

Contact Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350. Find @RefriedBrean on Twitter.