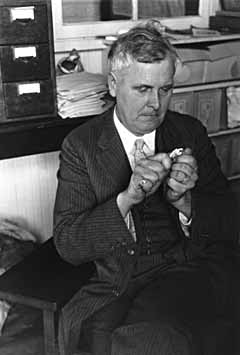

Mark Harrington

Mark Harrington knew within minutes that he was standing on something of monumental scientific importance.

The famed archaeologist was on the bank of the Muddy River in the Moapa Valley on a fall day in 1924. With him were James Scrugham, the governor of Nevada, and two brothers, John and Fay Perkins, members of a local pioneer Mormon family. Fay Perkins had found odd Indian artifacts along the river, sent them to Scrugham, who sent for Harrington.

"We had not been there two minutes," Harrington recalled, "when my eyes rested upon a scrap of painted pottery lying on the sand beside a prickly mesquite bush. It was our first clue!"

Harrington examined the piece. It was a neat pattern in black on white, which Harrington's trained eye quickly identified as an early example of Pueblo craft, made at a time when they were just beginning to develop their characteristic pottery. In New Mexico and Arizona such a find might possibly be expected. But not west of the Colorado River in Nevada.

"Look at this pottery, it's early Pueblo," he said excitedly, and handed the shard to Fay Perkins, who tossed it back casually.

"I wouldn't get all worked up and excited over just one piece," Perkins advised. "You'll find that kind of stuff scattered all along the river here for five or six miles."

"If that's true," said Harrington, "and you really saw all those old foundations you've been telling about, I'll bet we've found a regular buried city."

Harrington left the Moapa Valley the next day. He would return, and what he would find would exceed his wildest expectations.

"Even then," he wrote, "with all our enthusiasm over the new find, we did not realize just how old it was; that we had struck the trail of some of the very first Pueblos."

Many of Harrington's conclusions came into question in later years and many were disproved. Dr. Margaret Lyneis, professor of anthropology at UNLV, says his initial findings were "fundamentally right" and his chronology, with a few exceptions, was good.

"While many of his results got changed in later studies, he drew attention to the importance of the sites he excavated, and that resulted in further studies. All three of his excavations -- the Lost City, Gypsum Cave and Tule Springs -- were pioneering pieces of work."

Harrington knew Indian ways. In his career, he lived with or visited 43 Indian tribes and bands in North America and was adopted into several. He wrote fanciful adventure stories, usually set among pre-Columbian Indians, and always ethnologically accurate. These were published under his pen name, Ramon de la Cuevas (Raymond of the Caves). In later years, he would even try peyote, a powerful hallucinogenic drug used by some tribes to attain spiritual enlightenment. It is hard to determine from his cryptic account whether he was enlightened, but he was definitely impressed.

Mark Raymond Harrington was born on the campus of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor on July 6, 1882. His father, Mark W. Harrington, was curator of the university museum and taught geology, mathematics, botany and French.

From his earliest years, Raymond, as he preferred to be called, was fascinated by native American culture, and local Indian friends helped him learn some of their language.

When his family moved to Mount Vernon, N.Y., there were no Indians, but there was plenty of physical evidence that there once had been. Harrington dug up pot shards and arrowheads, which he eventually took to F.W. Putnam, head of the anthropology department at the American Museum in New York City. Putnam would become his mentor and lifelong friend. When his father's illness forced Harrington to quit high school, Putnam hired him as an apprentice field archaeologist and trained him on the job. He saved enough money to finish his education, culminating in 1908 with a master's degree in anthropology from Columbia University.

Harrington and a friend, Frank Covert, organized "Covert & Harrington, Commercial Ethnologists." Their business was arranging exhibits of Indian artifacts at schools, colleges and museums. He met George Gustav Heye, a banker who had made a fortune in Standard Oil stock and was fascinated with Indian lore. He hired Harrington to collect materials that would make up the inventory of the Museum of the American Indian in New York City. The young archaeologist's travels would take him to Cuba, the Ozarks and into the Southwest.

The chain of events that resulted in Harrington coming to Nevada began in 1911. In that year, James Hart and Samuel Pugh discovered a shallow cave in the west Humboldt Range, near Lovelock. Inside the cave was a fecal fortune in bat guano, prized as fertilizer. Hart and Pugh filed a mining claim on the cave and began to excavate. To their chagrin, the poop wasn't pure. It was contaminated with all manner of bows, arrows, baskets, pottery, clothing. So thick were the relics, they abandoned the claim.

The men kept the showiest goodies, and donated some to the Nevada Historical Society, which contacted the University of California, Berkeley. Between April and August of 1912, Dr. Llewellyn Loud took 10,000 specimens from the cave.

George Heye obtained a rabbit net and some other artifacts from the cave and showed them to Harrington in 1924. Heye sent Harrington to see if there was anything worth saving from the ravaged site, and Harrington invited Loud to join him.

The cave was a jumbled mass of bat guano, artifacts and dirt. In those days before carbon dating, the way an archaeologist usually determined the age of a site was by studying the layers of dirt and relics. Loud had not done this, simply cataloging the artifacts in "lots." Harrington found one tiny area of the cave floor undisturbed and was able to make an educated guess as to the antiquity of the site. By his reckoning, the earliest inhabitants moved in sometime around 2,000 B.C.; the last, about 900 A.D. His estimates were remarkably close. Modern studies have shown that the cave was occupied or used between 2,600 B.C. and 1850 A.D.

Among Harrington's findings was a bundle of very well preserved duck decoys. These had been fashioned from bundles of reeds, then decorated with the feathers of the birds being hunted. Harrington's find proved people had hunted and fished on the shores of ancient Lake Lahontan. When the lake dried up, the people departed.

While at work in the Lovelock Cave, Harrington was contacted by Gov. Scrugham concerning the mysterious relics and ruins along the Muddy River.

By 1925, Harrington was eager to tackle the excavation of the place Scrugham had named "El Pueblo Grande de Nevada."

When Harrington arrived, he was met by newspaper and magazine reporters, film crews and an astonishing number of private citizens.

To raise money for the project -- and to get favorable publicity for his state -- Scrugham threw a pageant, depicting the valley's prehistory and history. It was held May 23, 1925, at the end of the digging season. A replica of a Pueblo was constructed for a stage.

It is hard to imagine that such a home-grown spectacle would entice many people to travel so far on mostly dirt roads. But it did.

The Las Vegas Age played the story front page and wrote, "According to Mr. John Perkins, who caused a count of passing machines to be made at St. Thomas, there were more than 1,200 automobiles at the pageant. If each brought five people, an estimate that seems conservative, there were six thousand people at the pageant."

Harrington's right-hand men -- and close friends -- were George and Willis Evans, members of the Pitt River Tribe. A group of Zunis from New Mexico showed up and went to work, along with Indians of several other tribes.

"I always had a partiality for Indians and employ them in archaeological work whenever I can ... " said Harrington. "It is only right that they should have a hand in uncovering the ancient history of their ancestors."

On his initial expedition, 1925-26, Harrington's party excavated 46 prehistoric structures, the largest of which had nearly 100 rooms.

He determined almost immediately different cultures had occupied the site, the first a culture known as Basketmakers. He dated their time at around 1500 B.C. Modern studies, however, have indicated that Basketmakers lived in this area about 300-500 B.C.

The Basketmakers found at the site were characterized by long, rather than round skulls. These people practiced agriculture, wove fine baskets and cloth, but made no pottery. They did not use the bow and arrow, relying on the atlatl, a special stick used to hurl light spears called "darts."

"Fortunately for archaeologists," wrote Harrington, "these people had the custom of burying their dead and storing their belongings in caves so dry that specimens of practically everything they owned, even highly perishable articles made of fur and feathers, have come down to us in a remarkable state of preservation."

But to Harrington, the most exciting finds were those of the Pueblos. These were the people who built houses of stone and adobe. They were entirely dependent upon agriculture and grew cotton, which they wove into fine cloth. They seem to have mastered irrigation, since early settlers recorded finding many ditches running from the Muddy River. Harrington overestimated the antiquity of this culture, and later archaeologists set it at about 700-1150 A.D.

In 1928, Harrington became curator of the Southwest Museum in Los Angeles.

He represented the museum when he returned to Southern Nevada in 1929. The objective this time was to do a complete survey of the Moapa Valley, and to excavate a few of the more intriguing ruins not explored on the first expedition.

Harrington's survey recorded 77 ruins on a 16-mile stretch of the Muddy River. Meanwhile, a colleague, Irwin Hayden, began digging Mesa House, a large pueblo arranged in a courtyard fashion. He unearthed 84 rooms and single-family dwellings, most of them from the last period of the Pueblo occupation. Harrington believed that these single-story adobe structures were the precursors to the gigantic multistory pueblos that these people built in New Mexico and Arizona, after they left the valley sometime after 1100 A.D.

In 1930, Harrington began work in Gypsum Cave, which John Perkins had told him about in 1924. The cave is in a limestone spur of the Frenchman Mountain Range east of Las Vegas.

Harrington and his crew dug 8 feet into the floor of the cave. They found atlatl darts, indicating the presence of Basketmaker people, and they found huge deposits of dung, which Harrington surmised had come from a large animal. Further digging turned up the bones and a skull from a species of extinct ground sloth, (Nothrotheriops shastensis.) Then, at a deeper level, beneath the dung of the ice age creature, were more atlatl points, the remains of cooking fires, and evidence of vegetation that does not exist in the area today.

This raised an important question. Did these people live at the same time as the ice age sloth? Harrington produced bones that he believed had been split for their marrow, since they bore the marks of what seemed to be a stone knife. He concluded that the Basketmakers had indeed met the sloths, and he placed the time at 8,500 B.C. This was a revolutionary and controversial finding. And it was wrong. Recent radiometric tests have shown that the sloth leavings dated to 9,700-6,500 B.C., and the human artifacts went back to 900-400 B.C. This by no means settled the controversy among archaeologists, which continues today.

Equally controversial was Harrington's dating of bones and weapon points at Tule Springs. Amateurs had been turning up bones and artifacts there since the turn of the century. The site had first been excavated by scholars in 1932, when Fernley Hunter and Dr. Albert Silberling, under the auspices of the American Museum of Natural History, unearthed the bones of two ground sloths, a camelops, the largest of the American camels, and a partial skeleton of a mammoth. Among the bones, in an ancient campfire pit, they found an obsidian weapon point. So astonishing was this find that they unearthed the fire pit intact and shipped it to Dr. George G. Simpson at the American Museum of Natural History. Simpson was excited by the find, but hesitant to go against the prevailing wisdom that ice age beasts and man had never met. In 1933, he published a paper with the cautious title "A Nevada Fauna of Pleistocene Type and Its Probable Association with Man," which stopped short of stating that the ancient bones and human relics were from the same time period.

A few months later, Hunter turned the site over to the Southwest Museum and Harrington, along with Fay Perkins, went to Tule Springs. Harrington was overcome when he saw bones of the long extinct animals strewn among the black charcoal of the fireplaces.

"I think if I had been wearing a hat, I would have taken it off," he wrote.

In his opinion, the Tule Springs site was a camel hunter's camp and was "considerably more than 10,000 years old, more like 25,000 years old." He published his conclusions in an unequivocal piece titled "Man's Oldest Date in America."

Unfortunately, his dates have not stood up to the scrutiny of more recent examinations. It is now generally agreed that the shortage of human artifacts at Tule Springs does not yet allow scientists to make a solid connection between prehistoric man and animals.

In 1933, Harrington was summoned by the National Park Service, to direct the Civilian Conservation Corps in salvaging what could be found before the entire Lost City site disappeared under the new lake formed by Hoover Dam. The CCC excavated 17 more pueblos, laboring until water literally lapped at their feet. At the same time, Harrington directed construction of the Lost City Museum near Overton and restoration of ruins above the high water line.

His work for the government ended in 1935, and except for sporadic work in Southern Nevada, he spent the rest of his career exploring the antiquities of Southern California. He died on June 30, 1971, well established as a legend in his profession.

In a 1927 magazine article, Mark Raymond Harrington explained why he chose such a dusty, difficult and often frustrating career. He wrote:

"To follow the trail of a forgotten people, to play detective upon the doings of a man who has been dead 10,000 years or so is a thrilling pastime to an explorer under any circumstances. But when the trail leads into a rich virgin field never disturbed by the spade of the relic hunter, THEN your sunburned desert rat of an archaeologist thinks he has discovered a real paradise."

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full