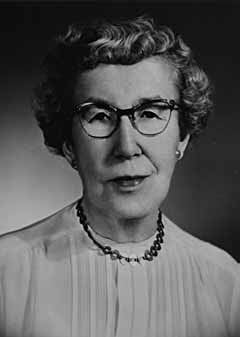

Maude Frazier

Maude Frazier was a lady to her toenails, but she wouldn't run from a fight, and she had no problem calling a spade a doggone shovel. She spent a long life making liars of those who said some job or another was no calling for a woman.

Arriving in 1921 to the whistle-stop town of Las Vegas, she stayed to build a good school system and even a university. She served repeatedly in the Nevada Assembly and was the first woman to serve as lieutenant governor.

"I was well aware that when a woman takes over work done by a man, she has to do it better, has more of it to do, and usually for less pay," Frazier wrote once. She was not happy about any of those conditions, but accepted them as realities. And if those rules have been softened, Frazier gets some of the credit.

People say that in her prime she was nearly 6 feet tall and straight as a teacher's ruler. She dressed in lace collars and wire-rimmed glasses, pursed her lips and sucked her teeth. But the schoolmarmish appearance belied the spirited personality within.

Frazier was born in 1881 and reared on a farm in Sauk County, Wis. Her family pressed her to become a teacher, as others in her family had done. But she questioned the choice in the opening paragraphs of her unpublished memoirs.

"It is quite possible that it was never intended by the good Lord that I should be a schoolteacher. At least not so soon after the turn of the Twentieth Century, when they were definitely a distinct species ...

"Early in the 1900s, women teachers suffered most of the restrictions of nuns, with none of the advantages they enjoyed. The members of the school board not only hired a teacher to teach, they made the rules for her private life and worked overtime enforcing them. She should keep her place as a teacher. How often this was heard! Nobody defined exactly what a teacher's place was, but everyone knew she should keep it."

She added, "I was cast in the wrong mold to fit comfortably as a teacher of that period. I was not able to understand why a teacher should not enjoy a ball game, skate on the pond in the winter and swim there in the summer. Why couldn't she have beaux just as the other girls did, wear dresses of gypsy red if they looked well on her, and dress her hair in the prevailing pompadour style?"

Even though her parents wanted her to teach, they did not believe in educating women beyond high school. It was still possible to get a teaching credential by passing an examination, so Frazier did, starting her career in the mining and timber camps of the region.

"Memories of my early mistakes because of lack of training haunt me to this day," she wrote, "but these errors which torment me yet were not the errors so evident to the school board. The board criticized me because I wore a dress with too many ruffles. They called them flounces.

"I rode a bicycle too, something which no nice girl would think of doing. Their objection to such a means of getting about always appeared incongruous to me, since the board members expect this same dignified teacher to perform all the undignified tasks of janitor work."

Frazier decided, "If I was going to be a teacher I was going to be a good one." On a salary of $22 a month, Frazier saved what she could and augmented it by working in the summer as a storekeeper and seamstress, until she had enough to start two years at a teachers college. She worked her way through, on finances so thin she owned but one winter skirt.

"There were plenty of girls better dressed at graduation, but all the diplomas were the same size, " she wrote later.

But her diploma won no more respect from the region's school boards. The next time she and her associates were asked to sign contracts, they "found that something new had been added. We must promise not to dance. Neither were we to play cards. This was to apply, not only in the town where we were teaching, but everywhere else."

"Of course as a group, we were scarcely what could be considered riotous livers, but as soon as we read these restrictions, our comments could have burned holes in asbestos."

Frazier refused to sign. Having met mining engineers who were enthusiastic about the emerging West, in 1906 she took a job as a teaching principal in Genoa.

The pride she must have felt in being hired was soon taken down a peg, when the superintendent explained that the vacancy she filled was created after a big fight on the school board. "Most of the board members blamed the principal, who was from a nearby town ... One member had moved that they elect their next principal from as far away as possible.

"So that was it," she wrote. "Distance rather than qualifications had gotten me this position. I might have been the best teacher in the world, or the worst."

But out here, a teacher's life was her own. The energetic Frazier throve on hard work and freedom. In Nevada, she learned to ride with cowboys and sometimes rode 12 miles to dance Virginia reels.

Over the next 15 years her resume would read like the itinerary of a politician running for governor. She taught at Lovelock, even then a stable agricultural community. Seven Troughs, a new mining camp, hired her to start a new school in a tent, and moved a brothel to make way for a schoolhouse. There were jobs in Beatty, Goldfield and Sparks.

Conditions varied wildly. Goldfield, prosperous in those days, could afford a fine modern school and a piano for every classroom. At Genoa, not even books were furnished, so students brought what they could find. These pupils weren't on the same page; they weren't even using the same books.

At Seven Troughs, coal had to be hauled so far that it cost $36 a ton, more than twice the price in cities served by railroads, so students and teachers wore multiple coats, fur-lined boots, and on windy days, wrapped themselves in blankets. So roughly constructed was the new building that "Every pencil dropped on the floor rolled through the cracks. When the supply ran low, a boy would crawl under the tent and retrieve them."

Yet it was blessed with miners' children, who knew what it was to be uneducated, and feared it. "There was never a complaint about too much home work. There was no playing hooky." The shack schoolhouse had what she called "the two essentials important to any good school -- pupils who wanted to learn, and an teacher who wanted to teach."

"A good school is a thing of the mind and spirit, and not a thing of gadgets," she wrote in her memoirs.

In 1921 she applied for a position as deputy superintendent in the State Department of Education. The vacancy involved supervising all public schools in Clark, Lincoln, Esmeralda, and Nye counties. "Four men had given up on that particular territory, saying nobody on earth could get over that desert country," she wrote.

No roads. Wild coyotes. Long stretches without water. She was warned of hostile denizens who would refuse her food or a place to sleep.

Frazier bought a used Dodge roadster she named Teddy "because he was such a rough rider."

"Teddy and I became a team as we covered the trail. Garage men were our friends. They drew crude maps on any scrap of material available ... made lists of supplies I must carry. I would need a shovel, an ax, tow ropes, two jacks, good tire pump, canteens of water, gas and oil. Neither must I ever be without an abundance of canned goods, which in turn necessitated a can opener."

She also carried two flashlights, plenty of magazines, and a deck of cards.

Her headquarters were at Las Vegas, then a town of 2,500, and at the time the best route to Goldfield and Tonopah was along the abandoned bed of the Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad, which the federal government had forced to close, during World War I, as a superfluous route. "The rails had been removed because Uncle Sam wanted the steel. Most of the ties had been taken out and used by desert dwellers in building their houses." This made a bumpy road indeed, and at some points autos had to drive in the ditch alongside the roadbed. "This ditch was filled with fine silt, which, at times, caused visibility to be zero. Often I had to stop and let the dust settle before I could see ahead of me at all."

Back when intercity speeds were limited by such conditions, rather than by state troopers, new speed records were announced by local newspapers as signs of progress. Frazier set one on this difficult route; The Las Vegas Age hailed her as first to drive the 180 miles to Goldfield in a single day.

She met teachers who made do even as she had. One young woman had jars full of scorpions and spiders to teach biology, and a free-roaming snake was the classroom mouser. "To me she was a perfect example of making teaching fit the community," wrote Frazier.

In 1927 she took a job as superintendent of the Las Vegas Union School District, consisting of two local elementary schools and the high school. (She was also principal of the high school.) This put her in charge during the population boom brought about by the construction of Hoover Dam.

She found a local high school so old and unsuitably built that she feared it would explode in flames, burning students alive. Fire did destroy the building, but not during school hours, so nobody was seriously hurt. Frazier and others worked all night salvaging desks and other equipment, and convened school the next day in temporary classrooms all over town.

Fortunately, Frazier had already persuaded the public to pass a $350,000 bond issue to build Las Vegas High School (now Las Vegas Academy), a school so architecturally memorable that it is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. She was criticized for building "rooms which will never be used."

Many wondered if the busy and stern Frazier ever had time for romance. Eva Adams, a pretty young teacher at Las Vegas High School who eventually rose to become director of the U.S. Mint, recalled in an oral history that Frazier did.

"There was a man who had a ranch outside of Beatty, and poor Miss Frazier had great struggles about whether or not to marry this farmer. And when she found out that he, and I'm quoting, 'hadn't the gumption to run a pipe from the well into the house,' she decided that she wasn't going to marry him," said Adams.

Frazier retired from the school district in 1946, but couldn't bring herself to take it easy. She ran for the Nevada Assembly in 1948, lost, then won in 1950. She served in the Legislature for 12 years.

Harley E. Harmon, who began his long career in public life about the same time, remembers her as an effective legislator. Legislation can be passed in Nevada by horsetrading, gladhanding, and a variety of other methods. "Her method was to do her homework," said Harmon. "She knew to the penny how much money was available, knew by heart how many students would be affected by a bill."

Her most popular issue was getting a college of some sort in Southern Nevada.

"Getting the college was hard, because Washoe County outnumbered us in the Legislature," said Harmon. Washoe, home of the University of Nevada, foresaw that a college in Southern Nevada would compete for funds, students, prestige and the loyalty of Nevadans.

In 1955 Frazier persuaded legislators to appropriate $200,000 for a Southern Nevada campus, but they attached a big, fat string. The money would be forthcoming only if Las Vegas raised $100,000 from private sources. R. Guild Gray, the superintendent of schools at that time, chaired the fund-raising effort, with the help of Frazier and Archie Grant. They kicked off the campaign on May 24, 1955, with a one-hour telecast featuring Strip entertainers as well as civic leaders and educators. They exceeded the goal by $35,000, and in April 1956, Frazier was allowed the honor of shoveling out the first spadeful of soil in what would become a junior college and, eventually, UNLV.

During her last term in the Legislature, Frazier fell and broke her hip while touring Hyde Park Junior High School. It wouldn't stop Maude Frazier. That same year, when Lt. Gov. Rex Bell died suddenly in office, Gov. Grant Sawyer appointed Frazier as a replacement. She was the first woman to hold the office.

Brent Adams, a Washoe County district judge who grew up in Las Vegas, knew her in those days. "She was up in the Legislature, coming back to testify on an education bill, and Floyd Lamb opposed it. She was hobbling out on crutches and Floyd spoke to her. He said, 'Sometimes you have to act like a politician.'

"She just whirled around on those crutches, glared at him, and snapped, 'I didn't expect you to act like a politician, I expected you to act like a senator.' "

Later, she was confined for a time to a wheelchair, and Adams visited her home. "She was frying chicken in her kitchen. She had this bowl of flour set on the floor. She would drop each piece of chicken into the flour, pick it out, and then she would throw it all the way across the room and see if she could hit the frying pan."

Interviewed by a local newspaper in April 1963, she asked the photographer to let her pose without crutches and asked the reporter not to mention them. "If you ever write about me don't associate me with these crutches," she said. "They're not typical of me and I don't intend to wear them forever."

Six weeks later, she died in her sleep. She never liked long speeches, and the Rev. Walter Hanne, presiding over her funeral at First Presbyterian Church, kept it to 15 minutes. Every newspaper columnist and editor in Nevada offered some tribute, but if Maude Frazier can be summed up in words, let them be her own:

"Our schools tend too much to uniformity. We turn out people who know the same things, do the same things, think the same way. Yet it has been the nonconformists, the people who dared to be different ... who have contributed most to the world -- the Edisons, the Wrights, the Marconis.

"Instead of trying to make people to fit into a certain mold, we should encourage them to furnish their own mold."

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full