Air Force memo: Creech, other drone operations spread thin

Crews such as those at Creech Air Force Base who operate drones for overseas combat missions are spread so thin that strain from increased demands for more Predator and Reaper patrols will cause long-lasting damage to the armed spy plane program.

That’s according to an internal Air Force memo from a commanding general reported Sunday by a New York-based website, The Daily Beast. The story quotes an unnamed intelligence service official saying, “It’s at the breaking point, and has been for a long time.”

The memo to Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Welsh from Air Combat Command Gen. Herbert “Hawk” Carlisle says leadership at the command’s Joint Base Langley-Eustis, Va., headquarters “believes we are about to see a perfect storm of increased (combat commander) demand, accession reductions, and outflow increases that will damage the readiness and combat capability of the MQ-1/9 enterprise for years to come.”

“MQ-1/9” is shorthand for the MQ-1 Predator and the larger, faster, higher-flying MQ-9 Reaper. Both are remotely piloted aircraft that are flown over trouble spots in the Middle East and Afghanistan to hunt “high-value” terrorist targets and kill or destroy them using laser-guided Hellfire missiles, or a mix of 500-pound smart-bombs and missiles in the case of the Reaper.

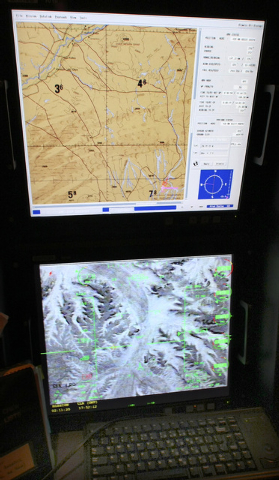

The operations are controlled via satellite links by pilots and sensor operators who sit at computer consoles in ground stations at Creech, 45 miles northwest of Las Vegas, and elsewhere in the United States and abroad.

Late Monday, an Air Force spokesman said he couldn’t release the Air Combat Command memo but provided an email response to a Review-Journal query.

“We’re mindful of the toll this has had on the force and recognize Airmen remain the service’s most vital resource,” wrote Lt. Col. Christopher P. Karns, chief of media operations for the Secretary of Air Force Public Affairs Office. “Continued sustainment of surge operations will have potential long-term impacts on training, safety, retention, manning, sustainment and combat capability.”

Karns said using Predator and Reaper drones to conduct intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) missions “is a top combatant commander requirement and will remain so for the foreseeable future.”

“Balancing ISR capability across the range of military operations with finite resources remains a challenge,” Karns’ statement says. “The Air Force continues to meet the growing needs of warfighting combatant commanders while building a right-sized capability.”

In order to meet those demands with direction from defense secretaries, combat air patrols have surged nine times in the past eight years, and the Air Force “has successfully sustained those operations to date,” Karns wrote.

The demand to spy on and attack Islamic State strongholds in Iraq and Syria has surged to the point that Pentagon leaders are calling for 65 combat air patrols (CAP) by April. A CAP, also known as an “orbit,” provides round-the-clock surveillance involving four drones. This has caused increased workloads for pilots, sensor operators, intelligence analysts, and ground crews who launch and maintain drones. As a result of the strain, training is short-changed and pilots are leaving the Air Force “in droves,” according to The Daily Beast story.

For comparison, the Air Force announced in May 2008 that it had reached a milestone by launching its 24th CAP two years ahead of its goal to have 21 Predator combat air patrols by 2010. At the time, the Air Force had 76 Predators deployed for combat out of its fleet of some 100, plus about a half-dozen operational MQ-9 Reapers.

A year after the 2008 milestone, the Air Force chalked up another Predator milestone on Feb. 18, 2009: flying 500,000 hours.

That achievement came at a breakneck pace because it took 12 years to reach 250,000 flying hours but only another two years to reach 500,000 hours — flying approximately 100,000 hours every six months.

As use of armed, unmanned spy planes spiraled upward after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the Indian Springs airfield, later dubbed Creech Air Force Base, became a hub not only for conducting overseas drone missions but also for training pilots and sensor operators.

Creech also hosted the Joint Unmanned Aircraft Systems Center of Excellence after it was established in 2005 to coordinate development and integration of drones such as Predators, Reapers and Ravens in the military. The center was dissolved six years later when the Pentagon eliminated the U.S. Joint Forces Command as part of budget cuts to save $430 million per year.

Meanwhile, to meet the demand and augment the supply of pilots and sensor operators, the Air Force expanded drone facilities to several other U.S. locations including California, North Dakota, Arizona and Texas.

Stephens Washington Bureau Chief Steve Tetreault contributed to this report. Contact Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308. Find him on Twitter: @KeithRogers2.