Nuclear workers fear new federal policy will make it harder to win compensation

WASHINGTON — Abelardo Garza was working near tanks full of toxic sludge at Hanford nuclear reservation in Washington state last Aug. 14 when one of his co-workers noticed a strange smell.

Within minutes, Garza's nose started bleeding. The next morning, he awoke gasping for breath.

It was the fourth time in five years that Garza would end up in the hospital after suspected exposure to chemical vapors at Hanford, a 586-square-mile site where workers once made plutonium for the bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan.

Now Garza, 65, worries that a new federal directive the government says was intended to speed up compensation claims by sick and dying nuclear workers could harm his chances of qualifying for benefits if his health worsens.

The directive, which became effective in December 2014, orders claims examiners to conclude that workers at Department of Energy nuclear facilities have not had any significant exposure to toxins since 1995 "in the absence of compelling data to the contrary."

To Garza, the wording of the government's directive feels like a dismissal.

"It's like telling me that this incident didn't happen to me," he said.

Workers at the former Nevada Test Site, now known as the Nevada National Security Site, fought a similar uphill battle eight years ago when flaws were found in methods the government to reconstruct exposures to radioactive materials.

Relief came in 2010, when the Advisory Board on Radiation Worker Health voted unanimously to grant them "special exposure cohort" status that allowed them to receive at least $150,000 in compensation without enduring tedious reconstructions of their exposures.

Since the directive was introduced, nuclear workers and their advocates have been fighting it. Some say it's time for Congress to intervene, fearing the directive signals an initial step toward trying to dismantle or rein in a $12 billion compensation program that has made payments to more than 53,000 sickened workers or their survivors since 2001.

Workers exposed to toxins after 1995 "will have to jump through a higher hurdle to prove that they are sick from exposure," said Terrie Barrie, founding member of the Alliance of Nuclear Worker Advocacy Groups.

"My own personal opinion," she said, "is they're trying to control the costs because it is expensive."

In an investigation published Dec. 11, McClatchy reported that 107,394 nuclear workers or their relatives have applied for compensation from a fund set up in 2001 to help those suffering from cancers and other diseases. More than 33,000 of those workers who received compensation are dead. In many cases, the money went to survivors.

Despite stronger standards, safety lapses continue to plague the nation's nuclear weapons and research sites.

A McClatchy examination of government records shows that 25 contractors have paid more than $106 million in fines for 75 incidents of safety-related misconduct at Department of Energy nuclear sites since 1995.

The records also reveal that at least 15 of those contractors paid $2.4 million worth of fines for 19 instances of misconduct related to toxic substance exposure.

The Department of Labor says the directive is aimed only at increasing efficiency and delivering workers faster answers on their claims, not at saving money.

In a 2015 memo explaining the directive, Rachel Leiton, director of the compensation program, stressed that claims examiners don't rely only on evidence provided by workers. They also consult industrial hygienists, a database on toxic substances at the nation's nuclear facilities and information supplied by the Department of Energy and its contractors.

Data inconclusive

McClatchy's analysis of compensation data obtained from the Department of Labor through the Freedom of Information Act was inconclusive about the effects of the directive.

The Department of Labor says it has no way to tell whether the directive came into play in any cases decided in the past year, short of reviewing each one individually.

At McClatchy's request, the agency analyzed cases that could have been affected by the directive. The low approval rate ticked up slightly, from just 23 approvals out of 200 such cases in 2014 to 21 approvals out of 169 last year.

The Department of Labor suggests that the low number of approvals for post-1995 workers' claims supports the agency's stance that improvements in safety and health programs, engineering controls and regulatory enforcement at nuclear facilities after 1995 have resulted in fewer workers falling ill — a conclusion that workers and their advocates reject.

Labor's own analysis also showed no evidence that the government's goal of speeding up claims adjudication is working.

The average time to reach a final decision on claims under the purview of the directive increased slightly from 2014 to 2015.

The average number of days to approve a claim went from 150 days to 191, while the average number of days to deny a claim jumped from 205 days to 213.

Most claims filed for toxin exposure by nuclear workers hired after 1995 — about 20 percent — come from employees, like Garza, who work at Hanford, which employs about 9,300 workers.

Since at least 1987, vapors from a toxic brew of more than 1,500 chemicals have been sickening workers at underground waste storage tanks at the site. The tanks hold 53 million gallons of concentrated radioactive and chemical sludge generated in producing nuclear materials for U.S. weapons. Gases that collect in the head spaces of the tanks can escape into the air.

'It's an outrage'

Studies over the years have documented the failure of the government and its contractors at Hanford to protect workers from the vapors.

The latest federally funded study, issued in October 2014, found that "ongoing emission of tank vapors … is inconsistent with the provisions of a safe and healthful workplace free from recognized hazards."

In the past two years, fears of exposure led at least 72 workers at Hanford's tank farms to seek medical exams after being in areas where vapors from chemical waste were suspected. Many smelled odors or experienced symptoms such as headaches, nausea, coughing, nosebleeds and dizziness.

In September, the state of Washington filed a lawsuit over the vapors, seeking better protection for workers from the federal government. That was followed by a separate lawsuit by Local Union 598 and Hanford Challenge, a Seattle-based watchdog group.

Hanford's toxic vapors undercut the government's assertion that exposure to toxic substances after 1995 occurred within existing regulatory standards, said Tom Carpenter, executive director at Hanford Challenge, a watchdog group in Washington state.

"It's an outrage," Carpenter said. "It's based on a fairy tale that the government likes to tell itself, and it's totally contrary to the studies and facts and oblivious to the studies the Department of Energy's expert panels and contractors have conducted."

Guidelines called insufficient

For workers at Hanford, the directive's assertion that stronger safety measures since 1995 have limited nuclear employees' exposure to toxic materials seems out of step with reality.

No guidelines, Garza said, required him or his colleagues to wear respiratory equipment at the Hanford tank farm that day in August when he became sick.

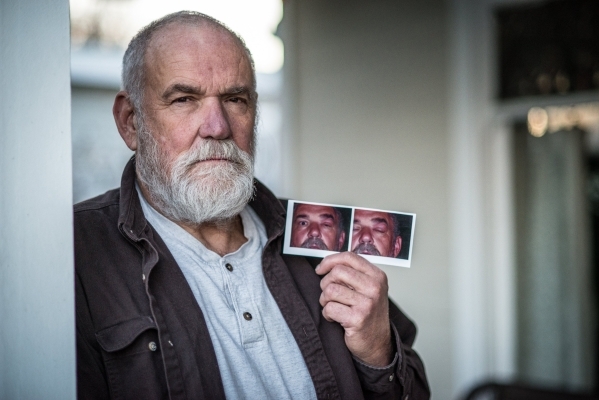

John Swain also was working in the tank farm at Hanford when he began feeling ill on Aug. 17, 2003.

"All of sudden there was something in the air that just made me shake my head," he said. He became nauseated and ended up in the hospital.

The next day, his eyes swelled up.

Swain returned to work but was plagued by trouble breathing and episodes of nausea. Sometimes his heart rate would spike, his thoughts became scrambled and he felt as if he would black out.

"I couldn't walk 40 feet and not be tired," he said.

Swain was diagnosed with reactive airways disease syndrome, or a respiratory condition, as well as toxic encephalopathy, a degenerative neurologic disorder, and peripheral neuropathy, a form of nerve damage. But Swain says it was a hard-fought battle to win any compensation from the federal government.

"The people that are making these decisions (in Washington), they need to have them fumes pumped into their office," Swain said. "Then they may say, 'Hey, wait a minute, it IS happening.'"

— Las Vegas Review-Journal writer Keith Rogers contributed to this report.