Bay Area fans still remember long-gone Golden Seals

SAN JOSE, Calif. — The line inside the SAP Center snaked around the concourse and seemed endless as fans patiently waited to take their trip down memory lane.

At the other end, at a long table, guys in their late 60s and early 70s sat and looked at one another in between greeting those who had waited to see them. One of them, Gary Simmons, said to another, Dennis Maruk, “I can’t believe they remembered us.”

Oh, they remember.

As the NHL celebrates its 50th year of expansion and special events are held in Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and St. Louis, one team had its own private memorial, as the San Jose Sharks paid homage last month to their departed cousins, the Oakland/California Golden Seals.

The Seals were part of the NHL’s “Expansion Six” in 1967 but lasted less than 10 years, bowing out unceremoniously in 1976 and relocating in Cleveland. Eventually, there was a merger with another expansion team, the Minnesota North Stars. The North Stars eventually moved to Dallas, where they dropped the “North” from the name and simply became the Stars.

The Seals? They are the franchise that expansion forgot. And as the NHL prepares to welcome Las Vegas to the league as its 31st team next season, it would be wise for the Golden Knights to remember the Seals’ sad story, if for no other reason than using it as a blueprint for how not to run a pro sports team.

DOOMED TO FAIL

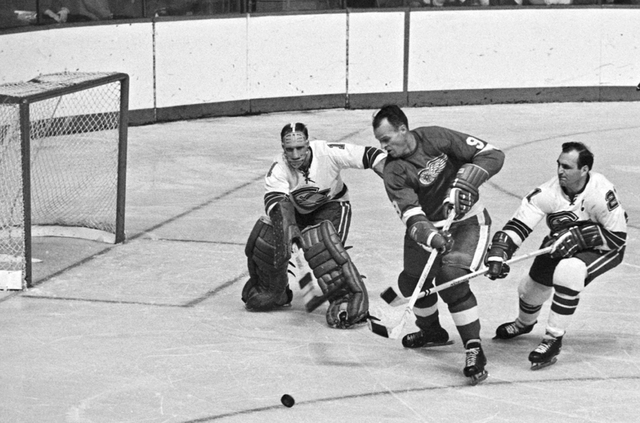

In their nine-year existence, the Seals went through five ownership groups. The team never posted a winning record, though it made the playoffs in 1969 and 1970. The franchise averaged fewer than 6,000 fans throughout its Bay Area stay, and because of constant unstable ownership, it never had a chance to succeed.

“It was doomed to fail from the start,” said Tim Ryan, the Hall of Fame broadcaster who was the team’s first public relations person in 1967. “Originally, they wanted the team to play in San Francisco, and the mayor at the time, Joe Alioto, was in favor of a new arena the city would build downtown.

“But the project got tangled up in political red tape and never got approved, so the team moved away from its fan base on the peninsula to the East Bay in Oakland, which had a brand new building opening up. The trouble was nobody wanted to go there. If they had built the arena in San Francisco, I think it would have had a chance to make it.”

Burt Marshall, a defenseman for the Seals from 1968 to 1971, said: “The fans didn’t want to drive across the (Bay) Bridge. It was like being the visiting team every night.”

OH NO, CHARLIE O

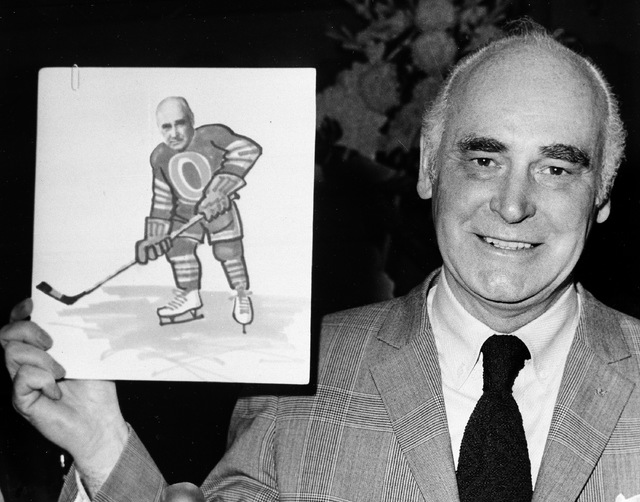

The original ownership group headed by Barry Van Gerbig ran out of money, and the NHL scrambled to find new owners to keep the team in the Bay Area. Eventually, Oakland Athletics owner Charles O. Finley bought the team in 1970 and tried to make the Seals a hockey version of the A’s. The colors changed to green, white and gold. He changed the name to California Golden Seals, eschewing the name Oakland. He didn’t spend money on salaries.

And then there were the white skates.

The A’s wore white cleats, and Finley thought the Seals should do the same with their skates. It wasn’t a good look, and the skates required lots of maintenance to stay white.

“I wasn’t fast to begin with,” Marshall said. “But those white skates were so heavy from all the paint, it made me feel even slower.”

But it was Finley’s unwillingness to pay his players that led to the Seals bottoming out as a franchise.

“Charlie Finley ruined the team,” said forward Norm Ferguson, one of several Seals to find refuge in the upstart World Hockey Association in 1972. “He was so cheap. I had a couple of good years in Oakland, but he was a tough guy to negotiate with. So when the WHA made me an offer to play in New York for a lot more money, I took it and ran.”

Finley didn’t just run off players. He lost his general manager, Bill Torrey, who had made the Seals competitive in 1969 through several shrewd moves. In 1972, Torrey took a job as GM of the expansion New York Islanders and built a franchise that dominated in the early 1980s with four consecutive Stanley Cup championships.

“It was no fun working for him,” Torrey said. “He was so stubborn, and it got to the point where your hands were tied and you couldn’t do anything.”

By the time Finley got out of the hockey business in 1975, the Seals were in such disarray that it would have taken a miracle to turn around the franchise.

GUILT AND GAFFES

The Seals were around for only nine years, but they were party to some strange and sad occurrences.

On Jan. 13, 1968, Minnesota’s Bill Masterton was checked by Oakland’s Ron Harris and Larry Cahan and hit his head on the ice. He died two days later.

On March 3, 1968, the Seals participated in an NHL doubleheader when they played Philadelphia in New York at Madison Square Garden after a storm had put a hole in the roof of the Spectrum, the Flyers’ home. The Seals and Flyers played in the afternoon, followed by the Blackhawks and Rangers at night.

The Montreal Canadiens took advantage of Finley’s ineptitude to land the team’s No. 1 draft pick with the option of using it in either 1970 or 1971. They chose 1971 and drafted Guy Lafleur, who had a Hall of Fame career with 560 goals, 1,353 points and four Stanley Cup rings.

Ernie Hicke, one of the players Montreal traded to the Seals for the draft pick, had no idea who Lafleur was.

“Montreal had like 300 guys in their organization; no way was I going to make the NHL with them,” Hicke said. “So when I got traded to Oakland, I was excited. Here was my chance to play in the NHL.”

As a bonus, Hicke played alongside his older brother Bill in his first season in 1970.

“They treated me great,” Ernie Hicke said of his two seasons with the Seals. “Best thing that ever happened to me.”

FROM SEALS TO SHARKS

After the 1975-76 season, the Gund brothers, the fifth ownership group, moved the team to Cleveland and became the Barons. Ironically, the Seals had their best year at the turnstiles that final season, averaging 6,944 a game.

“It was sad when they went to Cleveland,” said longtime fan Lou Rocca of Alameda. “They were great guys, and they always tried hard.”

The few fans of the team stayed loyal even after the Seals bolted the Bay Area. The team’s booster club still exists to this day and meets every other month. Len Shapiro, the team’s head of PR in 1976, has an amazing collection of memorabilia.

“The move to Cleveland was very tough to swallow,” Shapiro said. “I was totally depressed. I finally land my dream job and now it was gone.”

The NHL didn’t forget Oakland. From 1984 to 1991, 13 preseason games were played at the Coliseum-Arena, and nine were sellouts. George and Gordon Gund, who still owned the Barons and had merged the team with the North Stars, sold the North Stars in 1990 with the understanding they would own the expansion rights to a future Bay Area franchise. With San Jose building a new arena, the Gunds cashed in their expansion chip and the Sharks were born in 1991.

The Sharks played their first two seasons at the Cow Palace, the same barn the Seals originally wanted to play in when Van Gerbig owned the team but was deemed unsuitable by the NHL in 1967.

This season, just before the opening faceoff on Jan. 7, the former Seals, clad in Sharks jerseys, were introduced to the SAP Center crowd of 16,856, many wearing Seals jerseys or green T-shirts with the old Oakland Seals logo they received at the turnstiles. The fans rose and gave the Seals players a standing ovation.

“That was wonderful,” Marshall said. “It’s been so long. You wondered if people still remembered us.”

They did. And still do.

Contact Steve Carp at scarp@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2913. Follow @stevecarprj on Twitter.