Las Vegas may be loud but Nevada ranks high for quiet in Park Service analysis

Your typical tourists don’t come to Las Vegas in search of peace and quiet, but it’s all around them if they know where to listen.

Nevada has some of the quietest spaces in the country, according to a National Park Service analysis.

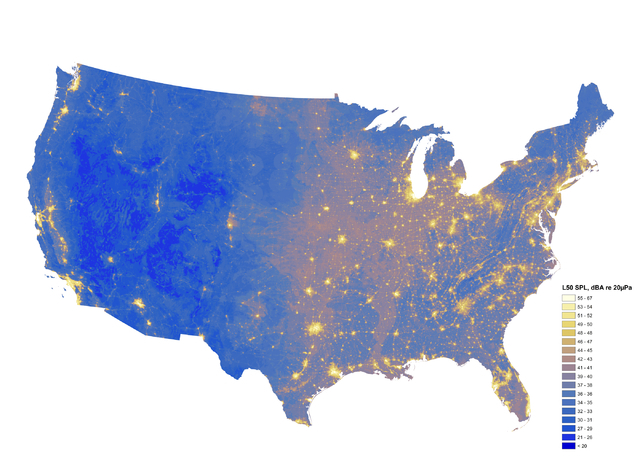

On detailed soundscape maps produced by the agency the Silver State scarcely registers for either human-caused noise or the background buzz of nature.

If not for the big, noisy blob of Las Vegas, Nevada would easily beat out Wyoming as the nation’s capital of quiet.

“We have some of the areas least impacted by human noise,” said Ashley Pipkin, a Nevada-based Park Service acoustic biologist. “It’s the low population that really contributes to that low noise.”

Then there’s the clatter of nature itself. Things such as flowing water, animals, wind in the trees and pelting rain all produce natural sound — except in places with few trees, little water and comparatively low wildlife populations.

“This is why Nevada is naturally quiet,” said Pipkin, who is based at Lake Mead National Recreation Area but travels the West collecting noise levels and assisting with acoustic research for the Park Service’s Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division.

Based on her fieldwork, Great Basin National Park in Eastern Nevada is a terrific place to experience the unspoiled sounds of nature. Lake Mead? Not so much, thanks to all the noisy motorboats, tour helicopters and commercial airliners.

Pipkin’s division produced the soundscape maps — and continues to refine them — as part of an effort to inventory noise levels in park sites across the nation. The maps are based on about 1.5 million hours of actual acoustical measurements taken in almost 500 different parks, cities and rural areas to develop a predictive model for the entire country.

The goal is to call attention to noise pollution. According to the Park Service website, protecting natural sounds is not only “good for both ecosystems and the quality of visitor experience” but is required under the agency’s mandate to conserve special places “unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

“Research into the impacts of noise pollution have only really taken off in the last 15 years,” Pipkin said. “I still talk to people all the time who say, ‘Noise pollution? What’s that?’ But I think it’s becoming more and more common for people to understand the impacts that sound can have.”

For wildlife, those impacts can be substantial. For example, Pipkin said, noise from human activity can limit the range of an owl’s hearing and keep it from catching prey, or it might silence frogs that use calls to attract mates and confuse predators.

But ambient noise can also influence human health, something Pipkin knows from personal experience.

She used to live in Henderson next door to a man who liked to cut his lawn at 6 a.m. The sound of the mower registered inside her bedroom at well above the decibel level recommended by health experts, she said.

“I moved out of that place,” she said.

Fred Bell knows all about escaping the noise to explore Nevada’s silent side.

For the past eight years or so, he has traveled to quiet corners of the state to record nature sounds using high-end listening equipment he assembled himself. His unusual hobby requires him to get up before dawn and sit motionless for minutes or even hours at a time, all while tracking airline flight patterns and other noise that could spoil his recordings.

He isn’t surprised by the Park Service’s assessment of Nevada.

“They don’t call the Great Basin Desert ‘the big empty’ for nothing,” he said. “In a lot of it, there’s nothing to record. It’s open sagebrush desert. There’s no songbirds. There’s no insects.”

But even in places that seem quiet, it’s increasingly difficult to escape the clatter of civilization. Bell said a commercial air route passes directly over the otherwise-pristine Great Basin National Park.

That’s why soundscape maps like the ones the Park Service produced are so important.

“You have to have a baseline of what you’re losing,” he said.

Bell worries that by drowning out and driving away the sounds of nature, we’ll lose an important connection to the world around us.

“Hearing natural sounds without man-made noise might be the most unappreciated extinction of our times,” he said.

Contact Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350. Follow @RefriedBrean on Twitter.