Henderson boy, 8, survives four pediatric strokes

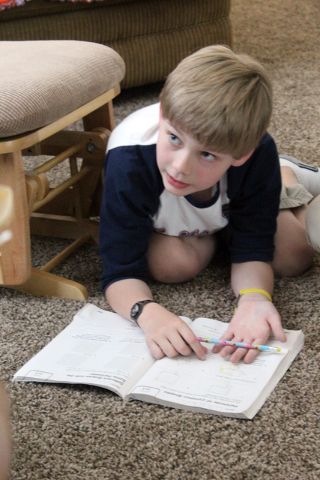

Larson Foster lays on his stomach playing an iPad game.

“I love ‘Plants vs. Zombies,’ ” he says, looking up briefly before returning to the game.

In many ways, he is a typical 8-year-old. But his story sets him apart.

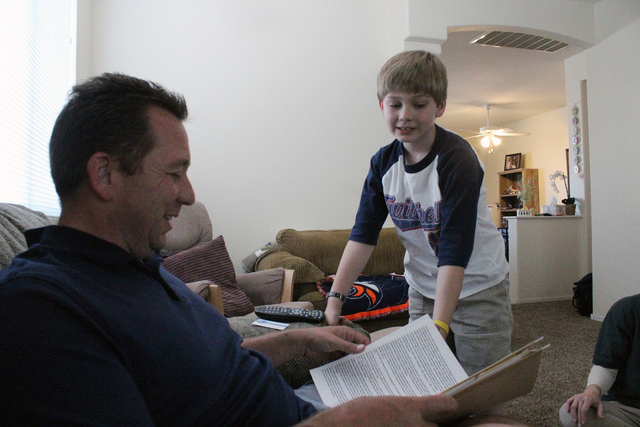

“My name is Larson Foster, and I am a four-time stroke survivor,” he says, reading from his journal — it is a script he uses when he meets politicians, doctors and anyone else who is curious about his story.

STROKES CAN HAPPEN TO ANYONE

Pediatric strokes happen more often than people realize, according to Mary Kay Ballasiotes, founder of the International Alliance for Pediatric Strokes (IAPS). After her daughter suffered a perinatal stroke nearly 20 years ago, she went on a quest for more information, only to discover limited resources were available.

She created the alliance in 2013 to help address the issue, partnering with organizations such as the American Heart and Stroke associations.

According to her nonprofit, strokes in children up to age 15 are estimated to happen to nearly six out of every 100,000 people and affect one in every 2,300 to 5,000 newborns. She said that, due to limited data, it’s hard to isolate the exact number.

Of children who have strokes, between 20 percent and 40 percent have more than one, which is what happened to Larson.

Beyond trying to gather information on pediatric strokes and resources, Ballasiotes has been reaching out to families who have personally dealt with the issue, which is how she found the Fosters.

Larson’s parents, Henderson residents Deanne and Larry Foster, are still trying to piece together what happened to their son. But pediatric strokes are something that even doctors are still trying to understand.

HENDERSON FAMILY SEARCHES FOR ANSWERS

Larson’s strokes started two years ago.

“He woke up really early,” Deanne said. “He was going really fast, doing these karate moves all over the room. Then he just fell.”

He hit the floor and screamed in pain. Every time he would get up, he would vomit.

They took him to urgent care, where a doctor said he was just suffering from migraines.

“I thought something else had to be wrong,” Deanne said. “I had no clue what. I just knew something wasn’t right.”

They took Larson home with prescribed medication. Hours later, he was exhibiting strange, lethargic behavior, provoking concern and nudging the family to bring him to the emergency room.

They received the same diagnosis.

“So they gave us more medicine and sent us home,” Deanne said.

The next morning, Larson woke up screaming and vomiting again. The family returned to the ER.

The doctors ran more tests and not only discovered that Larson had a stroke but that this was his second one in the last few months.

Thinking back, Larry remembered a time when Larson was sick.

“We thought it was the flu,” he said, “or maybe food poisoning. He projectile vomited in the middle of the night.”

But Larson never had any type of injury or situation commonly associated with a stroke.

The family went on a search for answers. They scheduled appointments with doctors — they said there really isn’t a pediatric stroke specialist in Las Vegas — and took to the Internet, trying to find information or other people dealing with the same situation.

It was on a trip to California a few months later that Larson had his third stroke. Once again, he woke up with head pain and slurred speech. Knowing a little more this time around, his parents took him to the doctor.

From there, Larson went on a daily regimen of aspirin and another prescription while he waited to see neurologists and other experts at UCLA. In order to get there, he first had to go through a series of tests in Las Vegas.

On the way to an early morning doctor’s appointment a few months after his third stroke, Larson did something out of character.

“He fell asleep in the car,” Deanne said. “Usually, when he is up in the morning, he is up.”

Larson slept off and on during the ride, in the waiting room and even in the triage area. He would wake up sporadically so nurses could get some stats — his height and weight and to check for vitals.

A nurse went to check his eyes after he fell asleep another time and realized he was unresponsive.

“They started giving him chest rubs and doing everything they could to try and wake him up,” Deanne said.

The doctor rushed him for tests including a CT scan. It was his fourth stroke and sent him to the intensive care unit.

“He slept most of his time there,” Deanne said.

When Larson woke up, he couldn’t talk or move his arms. A specialist discovered he had a vertebral artery dissection (a flap-like tear to the artery’s inner lining) on the back of his neck.

Even though to this day the family doesn’t know how it occurred, they had found what was responsible for the strokes. Finally making their way to UCLA, the Fosters were advised on how proceed, but the only approaches recommended for pediatric strokes are guesses at best.

The tear healed over a few months, but Larson is still on medication since the doctors don’t know if it’s better for him to be on or off of it.

In many aspects, he has made progress: As a first-grader at Twitchell Elementary School, he spends part of his school day in general education and the remainder in special education, getting specialized lesson plans.

WORKING TO CREATE AWARENESS

IAPS is trying to create awareness of the issue with fliers and fact sheets it hopes to distribute.

“We would love to get these (fliers) at every back-to-school type event,” Larry said.

The fliers include information such as risk factors and warning signs for perinatal and pediatric strokes, which affect children ages 1 month to 18 years.

Besides educating the public, the Fosters also want to be a resource for families going through a similar situation. The last two years, they have navigated everything from coping to paying for countless doctors’ visits. They said they have found resources for both and have most of Larson’s medical treatments and checkups covered through assistance for which they qualified.

Part of the mission of IAPS is also to raise awareness in the medical community.

“I’ve done presentations on this, and medical staff sit in disbelief,” Ballasiotes said.

Larson has since returned to the ER for head pain. When he tells the doctor he feels like he is having a stroke, he said the doctor assures him “children can’t have strokes.”

“I have had four,” Larson said, repeating how he responds to any doctor who offers that answer.

The American Heart and Stroke associations’ local chapters plan to host the 26th Annual Heart Ball at 5:30 p.m. April 23 at the Four Seasons Hotel, 3960 Las Vegas Blvd. South. The event is designed to raise money and awareness for issues such as pediatric strokes. The Fosters are set to be recognized at the event.

“We believe the Heart Ball is one of those mechanisms to help raise awareness within our community and raise dollars for outreach and research efforts,” Larry said.

IAPS is launching a campaign to collect stories from people across the country to bring awareness about pediatric strokes. Visit united4pediatricstroke.org or facebook.com/LoveForLarson.

To reach Henderson View reporter Michael Lyle, email mlyle@viewnews.com or call 702-387-5201. Find him on Twitter: @mjlyle.

Heart Ball

The American Heart and Stroke associations' local chapters plan to host the 26th Annual Heart Ball at 5:30 p.m. April 23 at the Four Seasons Hotel, 3960 Las Vegas Blvd. South. The event is designed to raise money and awareness for issues such as pediatric strokes. The Fosters are set to be recognized at the event.

Attire is black tie optional. A silent auction and cocktail hour are planned, to be followed by the program at 7 p.m.

Individual tickets are $350. Visit tinyurl.com/jk33q5h.