INSIDE CITYCENTER

My first work day at CityCenter -- the largest privately financed project in U.S. history -- starts in the pitch black hour of 4:30 a.m. It's still crisp and cool outside, eerily quiet and calm, when a crush of cars converge onto Dean Martin Drive for the 6 a.m. shift change. CityCenter has 8,182 people working three shifts, 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Construction trades must arrive an hour early to combat gridlock traffic along the single-lane job site access road. An 11-story, 7,200-space employee garage was one of CityCenter's first completed project components. But spaces fill fast, since the garage is also shared with Bellagio resort employees. Latecomers must use one of three remote overflow parking lots that require a short shuttle trip or long walk. Many workers ride motorbikes, zipping perilously in between car lanes, for superspeedy travel times.

Upon arrival, new hires are corralled into a mandatory two-hour orientation held inside a makeshift classroom in the employee garage basement. A safety trainer from Perini Building Co., the project's general contractor, leads the discussion.

It feels like the first day of school. There's excited talk and off-color jokes, old friends and nervous glances. People separate into groups: Ironworkers sit with one another; carpenters find seats side by side; and Spanish-speaking laborers cluster together. The room fills up with 70 men in their 30s, 40s and 50s. They form a loose tribe that shares a collective construction culture. They're similarly outfitted in blue denim jeans and cotton T-shirts, wearing goatees and handlebar mustaches, with tattooed arms, sunburnt skin and heavy leather boots. Everyone comes equipped with plastic lunch coolers and well-worn hardhats covered in stickers of employers, previous projects and certifications. Stickers serve as merit badges narrating a worker's personal history and experience level.

Andy Campbell, a former paramedic, delivers the orientation speech. Everything is translated into Spanish.

"A lot of people are talking smack about this project," Campbell said in a combative tone. "We are doing our best to remove the knuckleheads to make it as safe as possible."

Everyone gets employment paperwork. It, too, is translated into Spanish. Specific instructions are delivered for proper completion. The project's no tolerance policies are explained. Alcohol and drugs are prohibited as is graffiti, horseplay, scuffling, wrestling, running and failure to report accidents. Everyone must sign a legal waiver stating they understand the policies and the consequences of not following them.

Violating any item can result in immediate termination, a lifetime ban from MGM Mirage projects and a minimum one-year suspension from any Perini job. A stack of revoked work cards, including those from superintendents and managers, is piled high at the front of the room to underscore the point. The talk emphasizes workers' responsibility for their own safety and welfare and the safety and welfare of those around them.

"A foreman or project manager oversees at least 30 people," Campbell said. "They aren't standing over us like an umpire watching every move we make."

An average CityCenter journeyman makes $80,000 a year, which is more than many college graduates earn. An often-repeated message is that project officials want workers to earn fat paychecks and live to spend them. A souring economy, rising unemployment and looming holidays are other touchstones used to encourage worker safety and productivity.

"Is it worth losing your job?" asks Campbell, who gives the same orientation speech once a day to groups averaging 100 or more. "Communicate with each other, work together and we'll get this job done."

New hires are shown the sprawling job site layout, including MGM Mirage's office building, dubbed "The White House" by workers; it's strictly off limits for field personnel. Perini's building is called the "Pentagon" for its warlike project planning and strategizing, while its management offices are referred to as "The West Wing" or brain center of CityCenter's construction operations.

The 76-acre property between the Bellagio and Monte Carlo hotel-casinos is a byzantine complex of big and small concurrent building projects. CityCenter is divided into three large blocks, each with its own managers, estimators and supervisors. A friendly but fierce rivalry exists between block teams, each vying for bragging rights and racing against one another to finish schedule milestones. Roughly 800 buggy carts help move supervisors around the job site. Cart parking is a huge issue, as is unauthorized cart use. Some drivers use a "club," or steering-wheel lock device, to deter others from "borrowing" their parked carts.

After orientation, a single-file line forms for breath and urine drug and alcohol tests conducted inside an adjacent plywood box. Next, workers are shepherded into a classroom for 10 hours of required federal safety training that takes place over two days.

CityCenter recorded six deaths in 16 months, earning it the grisly nickname: "CityCemetery." The owner and contractor, as a result, required me to sign legal waivers and provide a $3 million certificate of liability insurance before setting foot on site.

On June 2, workers picketed in protest of unsafe working conditions. The 24-hour strike resulted in Occupational Safety and Heath Administration 10-hour safety training for everyone on site.

"We didn't bat an eye at the idea," said W. Shelton Grantham, Perini's vice president of field operations. "It's a proactive way to make sure everyone goes home at night."

Yet the pickets thrust CityCenter into an unseemly spotlight. Some saw them as a politically motivated union ploy, a naked grab for public attention showcasing organized labor's strength, despite an employer-union safety training accord having been reached before the event. But both sides are happy now. Perini has since increased its safety staff to 34 people, while mandating that its subcontractors have at least one safety professional for every 40 employees.

Since the agreement, all new hires must provide OSHA 10 cards, which are good for life, or undergo on-site training. The average employer cost for the training is $500 per person. Yet, only 15 percent of CityCenter's work force now has OSHA 10 training.

Although new hires are immediately processed, it's much harder to find and train existing employees, many of whom hail from out of state and were on site before the union pact. Perini has since hired 14 trainers and created seven classrooms to get everyone up to speed. Unions are also helping train their own.

But who foots the bill?

Perini is paying for all of its employees; its subcontractors, which number in the hundreds, must pay for their staff. Many subcontractors are squawking at the expense and lost production time. The price for OHSA 10 safety training will likely result in a $51.5 million change order, Grantham predicts.

"We spoke to MGM about it," he said. "They haven't paid us yet. But they haven't said 'no' either."

So far, OSHA 10 may not be paying dividends. One safety official who asked to remain anonymous said it hasn't made any noticeable difference on site. A "lost work-time" project board inside the Pentagon confirms as much. The Mandarin Oriental condo-hotel tower, for example, had only gone three days without a recordable accident during my visit. The Aria tower, by contrast, had 25 days without an incident.

However, it's important to put the numbers in perspective. CityCenter is like no other project. Its construction payroll is $3.125 million a day. The job has recorded 24 million man-hours of work thus far. Incident numbers, when examined in context, drop to around the state average.

Workers seem happy about the training and the raised safety awareness. My OSHA 10 class consists of 40 or so people who are electricians, pipefitters, concrete finishers and operating engineers. Everyone stands, states his name, profession and years in Las Vegas. Workers hail from everywhere: Texas, Illinois, Florida and California; there's even a guy from England. The program covers one safety topic per hour, including scaffolding and confined spaces, materials handling and fall protection, among other things. Our instructors, who rotate every few hours, share personal anecdotes and job-site horror stories about friends and family members losing a finger, chopping off a toe, or falling to their deaths. The stories create a somber, emotionally-charged setting inside the classroom.

"This is a crapshoot out here," said Kim Murray, a local operating engineer. "One guy might fall off a 12-foot ladder and live, while another might fall and die."

Construction workers routinely risk life and limb doing their job, performing physically demanding labor under often uncomfortable conditions. Job sites are inherently fluid environments that change daily, even hourly. Workers must remain focused and aware of their surroundings and the people and heavy machinery around them. Yet workers surprisingly blame fellow worker missteps for mistakes and accidents.

"I think this is a damn good idea," Trent Vanoostendorp, a 20-year veteran plumber and pipefitter, said of the OSHA 10 training. "People take shortcuts, or they're trying to be heroes and rush work. It's your attitude that makes you safe."

Each OSHA 10 section features a simple multiple-choice test answered together as a group. By day two, classmates are bonding. First-day jitters are gone as guys kid one another and swap job-site stories. Many of them clearly aren't accustomed to sitting still in a classroom for 10 hours. It's not a bookish crowd. So instructors provide intermittent breaks, which many of them use to smoke, make cell phone calls or stretch out and rest for 10 minutes.

When training concludes, workers receive their OSHA 10 cards, enabling them to attain job-site badges. Security personnel check the badges when workers enter and exit the site. All workers must wear the badges, reflective safety vests, hardhats and protective eyewear, at all times while at CityCenter.

By day three, work begins for new hires. I meet Mike Janowski, a Chicago-native Perini superintendent, who takes me atop CityCenter's highest point -- the 600-foot-tall Aria hotel tower. We travel along the building's outer edge inside a mesh metal cage called a man-hoist that operates via a counterweight system.

The 5.9-million-square-foot high-rise is the development's crown jewel -- its largest and most prominent building. The view atop the 61-story, 4,004-room Aria is breathtaking, providing a powerful view of CityCenter's kinetic job site. Janowski excitedly shows me around his project, quoting stats and numbers, like someone who has lived the job. He's proud of the achievement, and rightly so. The soaring glass skyscraper is designed by architect Cesar Pelli, who also created the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, which held the world's tallest building title from 1998 to 2004. Aria will require 245,000 cubic yards of concrete and 1,700 construction workers to complete.

As we slowly return to ground level, I'm taken aback by CityCenter's boldness, complexity and size. The seven-building, 19 million-square foot complex is the equivalent of nine Empire State buildings going up simultaneously, or 324 football fields laid end to end. And, remarkably, the project is scheduled to finish on time in December 2009.

I give my thanks, say my short goodbyes to my new friends, and make the dusty walk back to my car. So I make it home safe and sound that day, which is the true construction worker's motto.

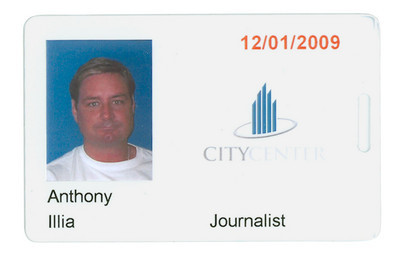

This story first appeared in the Business Press. Contact Tony Illia at 702-303-5699 or tonyillia@aol.com.

Editor's Note: Tony Illia, a longtime Business Press reporter, was recently granted unprecedented access to CityCenter — MGM Mirage's $9.1 billion mixed-use development taking shape on the Strip. He spent three days working as a new construction hire. Here's his tale.