Tony Hsieh’s will surfaced months ago. Plenty of questions remain

This past spring, a court filing in Tony Hsieh’s probate case was a legal stunner: It showed the late former Zappos chief had left a will.

Since then, however, the surprising turn of events has only become more bizarre.

The will surfaced under still-unclear circumstances more than four years after Hsieh’s death. New questions have since been raised at seemingly every turn, and there are still no clear answers on who key people tied to the will even are, let alone if attorneys are any closer to verifying the will’s authenticity.

District Judge Gloria Sturman said at a court hearing in late September that the will was an “unusual document” but that this “doesn’t mean it’s not valid,” a transcript shows.

With the five-year anniversary of Hsieh’s death approaching, here’s a look at key events — so far — in the ongoing saga of the tech mogul’s purported last will and testament.

Legal drama

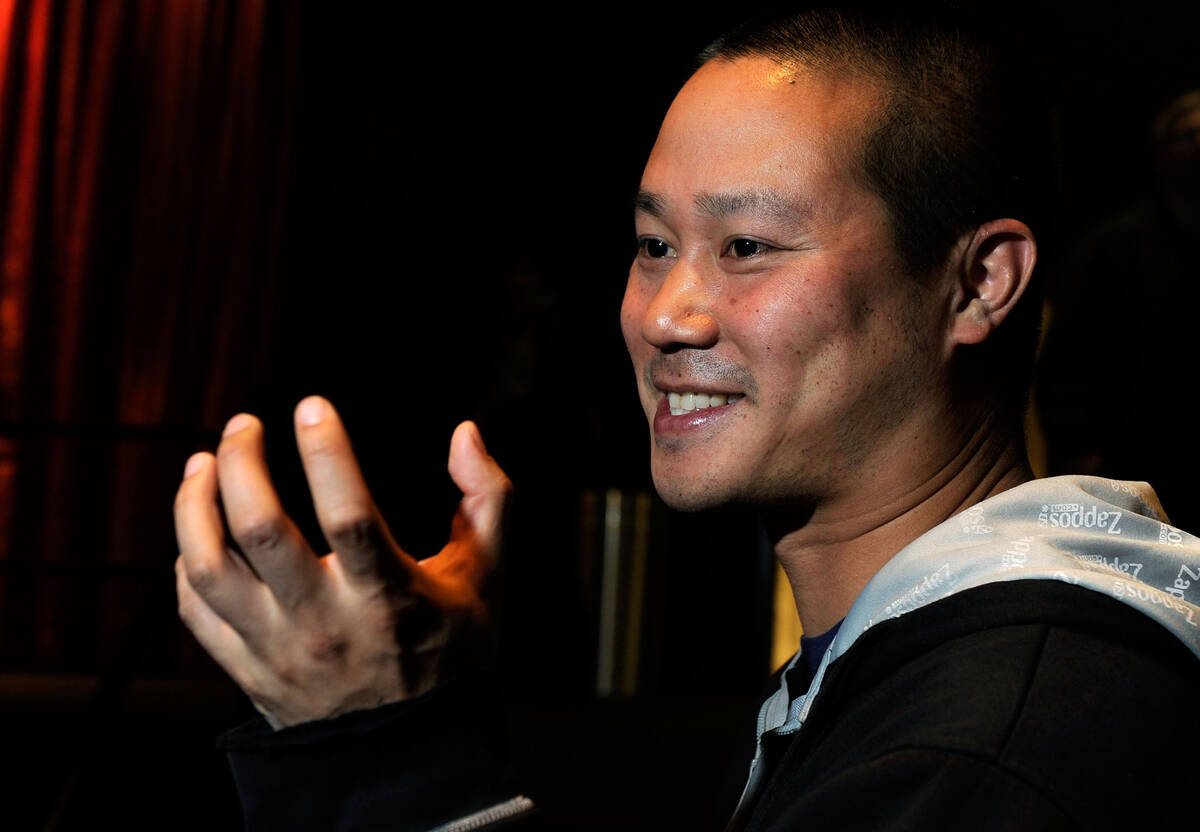

Hsieh, the former CEO of online shoe seller Zappos and face of downtown Las Vegas’ economic revival, died on Nov. 27, 2020, at age 46 from injuries suffered in a Connecticut house fire.

He was unmarried and died with a massive fortune, having sold Zappos to Amazon in a $1 billion-plus deal and assembled a sprawling real estate portfolio in his adopted hometown.

He became one of downtown Las Vegas’ biggest property owners, acquiring apartment complexes, office buildings, motel properties and other sites in the Fremont Street area through a $350 million side venture originally called Downtown Project. He also bankrolled bars, eateries and tech startups through the venture, now known as DTP Companies.

Hsieh’s father, Richard Hsieh, has been managing his son’s estate, and the dad’s legal team stated multiple times in court filings that the younger Hsieh died without a will.

His death was followed by a protracted legal drama involving lawsuits, creditors’ claims and detailed accounts of Hsieh’s drug use and erratic behavior in his final year alive, as well as allegations that people close to Hsieh took advantage of him financially as his health spiraled downward.

As part of his probate case, Hsieh’s family also filed more than 100 sale notices in court in a two-day span in early 2021 for his Las Vegas real estate holdings. By fall 2024, the family had sold a dozen properties locally for nearly $47 million combined.

And then, months later, a will surfaced.

‘No one knows who he is’

Law firms McDonald Carano and Greenberg Traurig teamed up to file court papers on April 17 with a copy of Tony Hsieh’s seven-page last will and testament — dated March 13, 2015 — and a letter describing how it was found. The firms were representing named executors in the will.

The will was found on Feb. 27 in the personal belongings of the late Pir Muhammad, according to the letter, which stated Muhammad had suffered from Alzheimer’s disease and was not aware Hsieh had died.

The letter did not say when Muhammad died or where he lived, nor did it provide any details about his career or his association with Hsieh.

Hsieh had named Muhammad an executor in the will and gave him “exclusive possession” of the original, in part to prevent anyone from destroying it, the will indicated.

But several people who knew Hsieh told the Las Vegas Review-Journal that they never heard of Pir Muhammad, and the newspaper found nothing that linked the name to Southern Nevada or confirmed who he was.

“No one knows who he is,” a source previously said.

A person named Kashif Singh wrote the letter explaining the will’s discovery. No contact information or details on Singh were provided in that filing, although according to subsequent court papers, Muhammad was Singh’s grandfather.

Probate and estate-planning lawyers also told the Review-Journal that the will was confusing, clunky and featured language and details they don’t normally see in such documents.

Southern Nevada probate lawyer Elyse Tyrell, for one, had never seen anything like it in her 30-plus years of legal experience.

As she described it, the document was convoluted and did not follow key estate-planning principles, and she figured Hsieh wrote it himself.

“This was absolutely not done by an attorney,” she said.

For instance, Tyrell noted that when someone signs their will, they revoke any prior versions. But Hsieh’s will referred to his “precautionary, alternate and contingent unrevoked prior Will” and indicated that his old one takes effect if his new one fails or is contested by his family.

The document referred to the previous version as his “backup will,” but Tyrell said that sort of thing doesn’t exist.

No answers

Attorneys Dara Goldsmith and Vivian Thoreen, representing Hsieh’s estate, started investigating the will, in part by serving subpoenas to landlords who owned apartment complexes where witnesses who signed the will apparently lived.

The will was signed by several witnesses, three of whom had a Las Vegas address listed with their name and signature in the document.

But property managers could not find any records that the witnesses had lived there, court records show.

The estate’s legal team also obtained an order for courthouse administrative records, including surveillance footage, on how the will was initially filed.

Singh filed the will in Clark County District Court before the two law firms submitted it with his letter, court records show.

As part of the courthouse records, the lawyers obtained a phone number and mailing address for Singh. But the call went straight to voicemail, which was a computerized or electronic voice, and Singh did not call back. The attorneys also sent him a letter, but he did not reply to that either.

The phone number had a 307 area code, which covers the state of Wyoming, and the mailing address was the same as a registered agent in Wyoming’s capital, Cheyenne.

Such businesses handle incorporation filings and other corporate paperwork.

Balochistan

Meanwhile, McDonald Carano and Greenberg Traurig filed court papers seeking to admit Hsieh’s will to probate.

They sought to have attorneys Robert Armstrong and Mark Ferrario appointed as co-executors of Hsieh’s estate and to remove Hsieh’s father as the administrator.

Armstrong, a trusts and estates lawyer with McDonald Carano, and Ferrario, a real estate litigator with Greenberg Traurig, were named executors in the will.

However, they were surprised to learn they had been named to that role, as they had not worked on Hsieh’s estate-planning documents and had never even met him, court papers show.

As part of the request to take charge of the estate, the law firms included a heavily redacted copy of Pir Muhammad’s death certificate, without explaining how they learned of it.

The death certificate was apparently issued by the government of Balochistan, a western province in Pakistan. It showed that Muhammad was a Pakistani national who was born in 1931 and died in October 2022 — more than two years before Hsieh’s will was reportedly discovered among his personal possessions.

Muhammad’s address, place of death, and other personal information were redacted.

Attorneys for Hsieh’s estate argued in court papers that the death certificate showed only that a person named Pir Muhammad died but did not show that it was the same Pir Muhammad who was named in the will.

The Review-Journal previously found more than 1,000 profiles on Facebook with the name Pir Muhammad. Many of them said they lived in Pakistan.

In a court filing in September, the lawyers for Hsieh’s estate outlined their wide-ranging efforts to investigate the will.

Among other things, they looked for any prior references to the will or people named in it, including by analyzing client files obtained from other attorneys who worked with Hsieh; internal documents and communications; depositions in litigation involving the estate; and Hsieh’s calendars.

They tried to find Singh and witnesses who signed the will, and they searched public records for trusts named in the document.

The end result: The attorneys basically came up empty.

Overall, they wrote that none of their efforts had yielded evidence that let them “verify or confirm the authenticity” of the purported will.

‘Somebody has to litigate this thing’

At a court hearing in July, Judge Carolyn Ellsworth declined to decide whether to admit the will to Hsieh’s probate case.

“There are quite a few questions in my mind, remaining, that should be … investigated by the estate as part of its due diligence,” Ellsworth said, adding that Hsieh’s probate case had been going on for years and then “suddenly a purported will pops up with some interesting and kind of unusual provisions, to say the least.”

At the hearing, attorneys for Armstrong and Ferrario argued that the document appeared to meet statutory requirements and was presumed to be valid.

Lawyers for Hsieh’s estate argued that they were still investigating the will and that just because there were names on a document did not mean that it was valid.

“We’re not sure who these people are,” Goldsmith said.

She also said that they still didn’t know where exactly the will was even found.

“We don’t know where in the world this document was located,” Goldsmith said. “We have no idea.”

At the court hearing in late September, Judge Sturman said that she wasn’t prepared to remove Hsieh’s father as the administrator and that she wasn’t going to grant the entire petition to admit the will to probate, a transcript shows.

But she would grant special powers of administration to Armstrong and Ferrario to allow them to act as proponents of the will and argue its merits and validity.

“Somebody has to litigate this thing,” the judge said.

Contact Eli Segall at esegall@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0342.