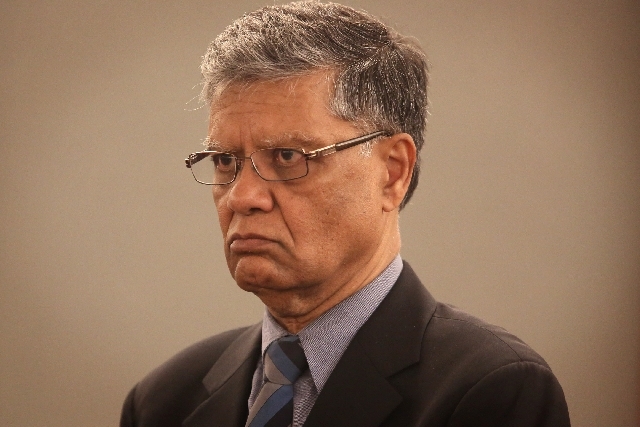

Victim testifies she went to Desai’s clinic well, left sick

The story told Monday by Patty Aspinwall mirrored fellow victims’ recollections about what happened to their bodies after they visited Dr. Dipak Desai’s Las Vegas endoscopy clinics.

Aspinwall visited Desai’s clinic in September 2007 and was met with a waiting room so crowded that it was soon standing room only.

Her appointment was scheduled for 9:15 a.m., but she wasn’t called into the changing room until 11:40 a.m. — a time she clearly remembers because she was concerned her husband would be late for work.

By 12:10 p.m., she was walking out of the center.

The turnaround seemed quick, especially considering that the nurse she saw moments before her release expressed surprise at her high blood pressure.

“I couldn’t talk. I woke up with laryngitis,” Aspinwall said. “I wasn’t sick when I came in, but I was sick when I came out.”

A few weeks later the symptoms began: brown urine, sore joints, a yellow complexion and nausea. During follow-up visits, she was told by doctors at the clinic that she did not have hepatitis C, a diagnosis that contradicted that of a physician at MountainView Hospital, she said.

That wasn’t the only contradiction unearthed Monday during the second week of a trial against Desai and nurse anesthetist Robert Lakeman, each of whom faces 29 criminal charges, including second-degree murder, criminal neglect of patients, theft and insurance fraud.

At the core of the trial is the use of the potent anesthetic propofol and the cleanliness of equipment used to inject it into patients.

Prosecutors allege Desai rushed patients through the clinic and admonished employees who wasted materials, even if they were dirty syringes.

Aspinwall said that when she awoke from the procedure, she was in a room alone, emerging from a propofol-induced sleep.

“I never saw the guy who said to count backward; I never saw a doctor,” she said, adding that the nurse who informed her of her high blood pressure was briefly bedside before disappearing.

Aspinwall’s description of a staff-free recovery room contradicted earlier testimony from nurse anesthetist Keith Mathahs, a onetime defendant who struck a deal with prosecutors to avoid murder charges that could have landed him in prison for life.

Mathahs, 76, told defense attorneys that anesthetists never left the side of patients until they were fully conscious and cognizant enough to be released from the clinic.

After the hepatitis C outbreak in 2007 and a subsequent federal investigation into the clinics, Mathahs was jailed in lieu of $500,000 — a target of the federal probe. He eventually entered into a plea deal with prosecutors, pleading guilty to five charges that could land him in prison for 28 to 72 months.

But Mathahs’ testimony last week and Monday could throw a hitch into his deal with prosecutors.

During cross-examination, Mathahs told defense attorney Richard Wright that propofol is a “multiuse” drug — meaning the drug could be injected into multiple patients until the vial is empty — and acknowledged that he had reused syringes.

Last week, while being questioned by Chief Deputy District Attorney Mike Staudaher, Mathahs said he would often change the needle and use the same vial if the same patient needed another injection. He testified that he never reused syringes.

On Monday, Wright’s questioning began to delve into Mathahs’ plea deal, a strategy that clearly upset prosecutors. District Judge Valerie Adair called a recess so that attorneys could figure out how to handle Mathahs’ testimony.

With Mathahs excused from the courtroom, Wright told Adair that it would clearly be “prosecutorial misconduct” if Staudaher informed Mathahs that he had violated his plea agreement.

“They spoon-fed him what to say on direct (examination), which is contrary to the truth,” Wright said.

Adair agreed to hold a separate hearing on the witness’ testimony at a later date.

Mathahs later explained to jurors that before coming to Las Vegas in 2003, neither he nor any of the nurses he knew reused syringes because of the risk of spreading infections. When he began working at Desai’s clinics, he bowed to the doctor’s pressure and changed needles but not syringes.

Mathahs said he expressed concern about the risk to Desai, but was told to reuse syringes anyway.

It was an agent from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention who visited the clinic and caught Mathahs reusing the syringe.

Inspections by that agency and the Clark County Health District led to the indictment of Mathahs, Desai and Lakeman.

Six patients were infected with the deadly disease, and one has died.

Aspinwall said she receives blood tests every six months, and while she no longer suffers from the symptoms, the disease remains in her bloodstream.