Guns used in Las Vegas shooting caught in legal limbo

The weapons one man used to kill as many country music fans as he could are now entangled in two complex court cases, born out of the massacre he inflicted nearly 18 months ago.

There is a will to destroy the guns and their accessories. There is a means, too. An anonymous donor in January offered to cover their value, so victims’ relatives who stand to collect from the killer’s estate won’t see them sold and circulated.

But the instruments of mass murder are also evidence, and a Las Vegas attorney involved in a federal lawsuit that stems from the attack is arguing for their preservation. So they remain in FBI custody, stored and stagnant as the families of the 58 people killed on Oct. 1, 2017, are forced to move forward.

“I’m racking my brain for anything that’s remotely similar,” David Horton, a University of California, Davis professor and expert on probate cases, told the Las Vegas Review-Journal.

“Normally in probate, you’re talking about value, and assets with value, and who gets the value,” Horton continued. “But now you have this quasi-toxic property and someone who has a claim to it, because even though it’s tainted, it has value. And then you throw in the private actions of the donor? My mind explodes.”

Horton said delays in probate cases are common, because it can be messy to wrap up someone’s affairs.

“This, however, is a level of complexity that I don’t think I’ve seen before,” he said.

Moral dilemma

When Stephen Paddock killed himself shortly after the attack — which left more than 800 injured — he did not have a will, so his mother inherited his assets. But she wanted nothing to do with the money, so she earmarked it for the estates of the 58 who were killed.

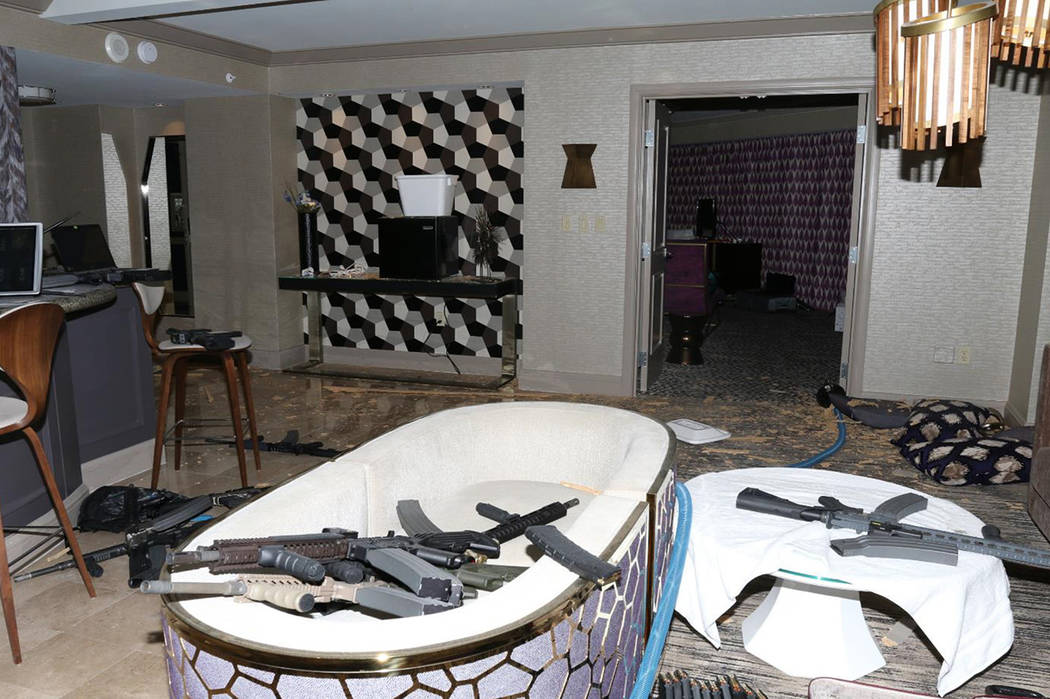

The most recent tally of his worth topped $1.3 million, according to court records filed last fall. That estimate included at least $62,000 worth of weapons and firearm accessories collected from his homes and Mandalay Bay suite at the time of his death.

The significant value of the weapons presented a moral dilemma, according to the attorney handling the probate case: Sell them, and collect money for victims’ families, or destroy them and forfeit their value.

“Due to the highly sensitive nature of the tragedy and this probate, it would be my personal preference that we petition the court at some point to destroy them,” Alice Denton said in September.

But the guns were still in law enforcement custody, so no action was taken.

The dilemma, which Horton called “extremely rare,” made national headlines in January. That’s when a California donor stepped in to offer a donation of $62,500 to ensure the weapons were destroyed.

Taken aback at the gesture, Denton planned to move forward with a petition to destroy them should law enforcement ever release them. That’s when Robert Eglet intervened.

Standstill

Eglet, a veteran Las Vegas attorney, is representing a group of victims suing Slide Fire Solutions, the manufacturer of the bump stocks that Paddock used to replicate automatic fire during the Route 91 Harvest festival attack.

The complaint argues, among other things, that the company lied on its federal firearms license application, stating that it manufactured guns when it really only makes bump stocks, which then are used on guns made by different manufacturers.

A nationwide Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives ban on the devices takes effect Tuesday.

The Slide Fire case likely won’t go to trial anytime soon. So when Eglet heard of the anonymous donor’s actions, he requested an emergency preservation order, which would hold the weapons in limbo until they can be used as evidence in Eglet’s case.

A magistrate judge approved the order, which subpoenaed anyone who may have custody of the weapons, including the FBI, the Metropolitan Police Department and Paddock’s estate.

The FBI didn’t reply. Metro argued that Las Vegas police do not have any of the weapons. And a lawyer on behalf of the special administrator tasked with preparing Paddock’s estate argued that the order was “premature, overbroad and too indefinite.”

Later in the document, the lawyer, Lisa Rasmussen, argued, “Without any assurance that the firearms will ultimately be destroyed, or even a possible date or event which would trigger the release of the firearms for destruction, the anonymous donor could very well withdraw his overly generous offer depriving the estates of the massacred victims of proceeds for the firearms and forcing the Special Administrator, at some later date, to sell them and put them back into circulation.”

The magistrate judge later issued an order that terminated the emergency motion, but in doing so, left what happens next “clear as mud,” Rasmussen told the Review-Journal.

“I advised my client about the order,” Rasmussen said, “but also said, if you come into possession of the guns, we should out of an abundance of caution not do anything until we give notice to the other parties in the Slide Fire action of any intent to dispose of them.”

Denton, the probate attorney, called the preservation order a “hiccup” in the complicated process of liquidating Paddock’s assets.

“We’re sort of at a standstill,” she said, regarding the weapons.

Eglet did not respond to a request for comment. But in a follow-up filing, Eglet noted that his clients “agree that destruction of the firearms and accessories is, ultimately, the best possible result in this terrible situation.”

The document gave no indication as to when that might happen.

Closure is needed

Mynda Smith, the sister of Neysa Tonks, a Las Vegas mother who was killed in the attack, was not aware of the recent complications surrounding the guns’ destruction.

She said the request to preserve the weapons as evidence was a “realistic concept.” But she hoped it wouldn’t delay the destruction any longer than necessary.

“There’s only so much evidence you can take off of a gun, in my opinion,” Smith said. “It’s not like there’s a million components to it or a million things to test. When their purpose is done, what they represented needs to no longer be.”

Smith said she knows the guns are “just things,” but those things were used to commit a “true act of evil.”

She worries that, without a more concrete guarantee, the weapons may one day find themselves in circulation. Or perhaps, on display.

“Give closure to the families and the survivors. Let that closure be in existence, so that they know that that door’s been shut,” she said. “I think that’s a better path than letting them just sit in a box.”

In both federal and state court, no hearing on the weapons is scheduled.

Contact Rachel Crosby at rcrosby@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3801.