Legendary illusionist Siegfried Fischbacher dies from cancer

Siegfried Fischbacher, half of the legendary illusion team Siegfried & Roy, has died from cancer.

His publicist, Dave Kirvin, confirmed Fischbacher’s death early Thursday. Fischbacher was 81.

“Funeral services will be private with plans for a public memorial in the future,” a statement from Kirvin said.

On Thursday, the Fremont Street Experience will celebrate Fischbacher’s life with special Viva Vision tribute starting at 6 p.m. and running at the top of every hour until 2 a.m. Earlier Thursday evening, MGM Resorts International announced it would pay tribute to his legacy by illuminating marquees at The Mirage and other properties on the Strip.

Sources indicate Fischbacher died Wednesday night from pancreatic cancer around midnight at Little Bavaria, the Las Vegas estate he shared with late partner Roy Horn.

Earlier this week the Review-Journal reported Fischbacher had been fighting pancreatic cancer in Las Vegas. He had a malignant tumor removed in a 12-hour surgery.

Related: Siegfried remembered as trailblazer among Strip entertainers

Fischbacher had told his sister Dolore that he is in the care of two hospice nurses and has asked to be cared for at his Las Vegas home. The German publication Bild reported Thursday morning that Dolore, 78, who lives as a nun in Munich, said: “He fell asleep gently and peacefully,” adding, “The death of Siegfried was a redemption.”

Horn died 8 months ago

In May, Fischbacher’s longtime stage and life partner Roy Horn died after suffering symptoms of COVID-19. Fischbacher’s most recent public appearance in Las Vegas was Aug. 26, at the dedication of Siegfried & Roy Drive at The Mirage.

The resort is home to Siegfried & Roy’s Secret Garden, and where Siegfried & Roy headlined to sellout crowds for 12 years until Horn was dragged offstage by the white tiger Mantecore (then known as Montecore) on Oct. 3, 2003.

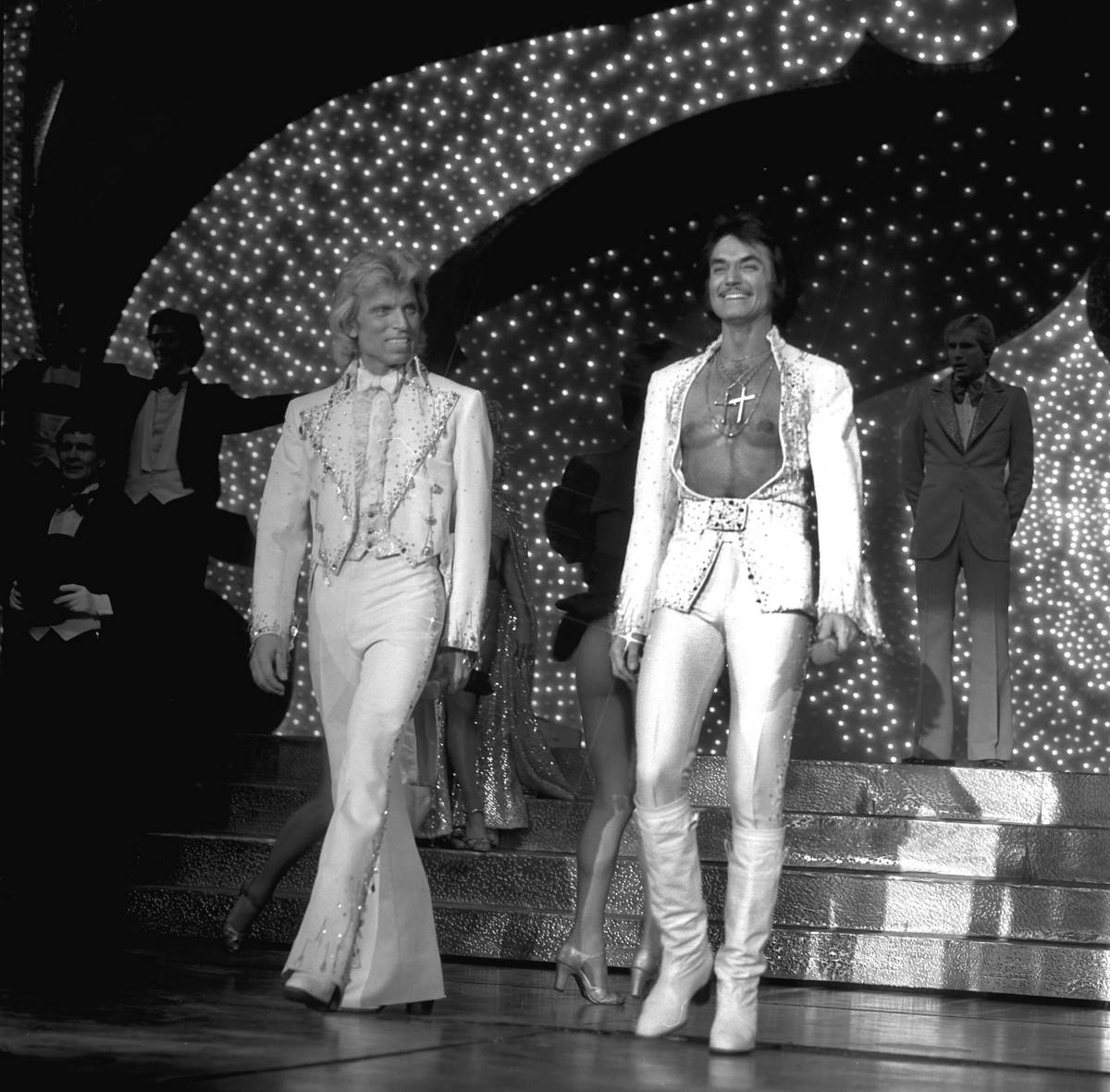

As one-half of the performing due of Siegfried & Roy — or, as their billing put it, “Siegfried and Roy, Masters of the Impossible” — Fischbacher helped to take Las Vegas magic shows to a new level. With ornate props, shiny outfits, an operatic manner and plenty of magic, flash and exotic cats, Fischbacher and Horn created a template that, despite others’ attempts to replicate it, remained theirs alone.

Started on cruise ship

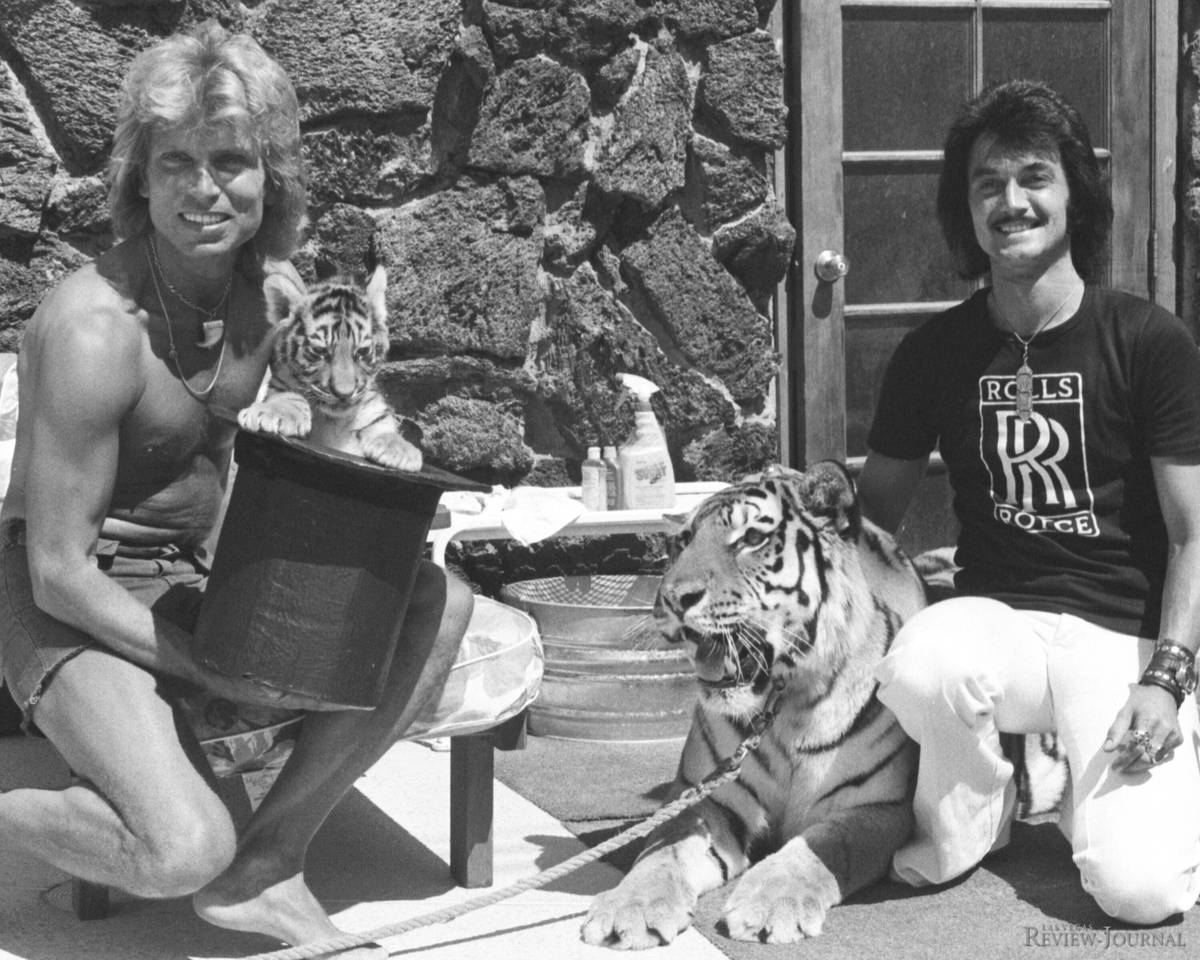

Fischbacher was raised in Rosenheim, Germany. He and Horn, who was born in Nordenham, Germany, met in 1957 while working on a cruise ship.

Horn was a waiter and Fischbacher — who had become interested in magic as a child — was a steward who entertained guests with magic tricks. Horn volunteered to assist Fischbacher, and the pair began to incorporate animals — including a rabbit and doves and, eventually, a pet cheetah Horn had smuggled aboard — into the act.

Fischbacher recalled that, after one show, Horn said: “Siegfried, disappearing rabbits are ordinary, but can you make a cheetah disappear?”

Fischbacher’s response summarized the principle that would guide their career together: “In magic, anything is possible.”

“In show business, in order to be successful, you have to be different,” Fischbacher told Vanity Fair in 1999. “And when Roy showed me that cheetah, it made all the difference. … I can tell you this: when I disappear from the lounge of that ship in the middle of the ocean, and reappear as a cheetah, this is better than pulling rabbits out of a hat. Yes, me and Roy, we are on our way. It is better than anything.”

Came to Las Vegas in 1967

They took their act to cabarets, nightclubs and theaters throughout Europe, including at the Folies Bergere in Paris. In 1967, they came to Las Vegas, landing a spot as a specialty act in “Folies Bergere” at the Tropicana.

Fischbacher told Vanity Fair that Las Vegas was “a gambler’s town” then, with entertainment “no more than just a rest period between gambling sessions — you know, bring on the scantily clad showgirls, strike up the band, tell some jokes, ba-ba-ba-ba-ba-boom, you’ve got a show.”

In 1970, they began a three-year run in “Lido de Paris” at the Stardust as a side act. From 1974 to 1978 they were featured in “Hallelujah Hollywood” at the original MGM Grand (now Bally’s), then returned to “Lido de Paris” to do an expanded 30-minute set.

Their first full-length, headlining show was “Beyond Belief” at the Frontier, which ran for seven years. In 1988, Steve Wynn signed the act to appear at his new Mirage, playing in a custom-made, 1,500-seat theater. They premiered at The Mirage in 1990 and eventually headlined 5,750 performances there, every one of them a sellout.

267 cast members

Their Mirage show — which, unlike most magic shows of the time, took the form of a story in which the duo were cast as adventurers facing off against an evil queen — cost a then-unheard of $30 million to produce and employed 267 cast and crew members. Alan Feldman, who headed publicity at The Mirage then and now is a distinguished fellow at the International Gaming Institute at UNLV, said the show not only revolutionized the Las Vegas magic show but also “had a broader impact on Las Vegas shows, period.”

“They were the first of anyone, really, to bring leading Broadway and West End designers and directors and choreographers into a Las Vegas setting to help stage a show,” Feldman said. “The creative team that was around ‘Siegfried & Roy at The Mirage’ was practically a who’s who … (of) incredible people who had an incredible list of credits.”

The result was a show that “was as deep and as rich and as powerful and as symbolic a show as you could find anywhere, if you chose to notice it,” Feldman said. “You also could choose to just be awed by it —‘That’s the most amazing thing I’ve ever seen’ — but if you chose to, you could see love and death and light and dark and resurrection. It was an incredibly artistic show.”

Michael Green, an associate professor of history at UNLV, called Siegfried and Roy “a bridge” between the classic single-performer/production show model of Las Vegas entertainment and today.

“We tend now to think of Las Vegas entertainment as spectacle,” he said. “The spectacle used to be the showgirls and the big names. Today, it’s the Cirque shows with all of the technology that makes it possible. They’re the bridge.”

Unlike most shows of the time, Siegfried and Roy’s Mirage show also was “family entertainment,” Fischbacher noted in 2013. “That’s what we started.”

Last appearance in 2009

Siegfried and Roy performed at The Mirage until Horn’s career-ending, act-ending injury. However, Siegfried & Roy did make one more appearance several years later, on Feb. 28, 2009, at the Keep Memory Alive Power of Love gala at the Bellagio.

In a 1999 Vanity Fair profile, close friend Arnold Schwarzenegger summed up Fischbacher and Horn’s legacy by calling them not only the “most spectacularly successful entertainers in the world,” but also “the greatest immigration story I know: two guys who came over to this country, starting with nothing, who have made their dream come true.”

Fischbacher and Horn were longtime Las Vegas residents who often could be seen at the doctor’s office, gym or any other place Las Vegans would go.

“They had a deep and abiding love for Las Vegas. They believed Las Vegas gave them the opportunity to grow and thrive and become the artists they are,” said Feldman, who last year ran into Fischbacher and Horn as they were going to see a movie at Red Rock Resort.

‘Larger than life’

They “were larger than life,” Feldman said, “but both of them, especially Siegfried, had moments where they could be unbelievably down to earth.”

“Siegfried, during the last few years, loved nothing more than going to the Secret Garden (at The Mirage) and just interacting with people,” Feldman said. Fischbacher would pose for pictures with visitors and give them SARMOTI (Siegfried And Roy, Masters Of The Impossible) coins that he would pull out of thin air.

“I saw it happen dozens of times,” Feldman said. “It was just extraordinary, that joy he got from doing magic. He got such joy out of making people say, ‘Wow,’ and, honest to God, it didn’t matter if it was it was Queen Elizabeth or Elizabeth Taylor or Elizabeth from Bloomington, Indiana.”

In fact, Feldman added, “he was more comfortable if it was Elizabeth from Indiana.”

Kirvin, Fischbacher’s publicist, said in lieu of flowers, donations can be made to the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health at www.keepmemoryalive.org.

Contact John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com. Follow @JJPrzybys on Twitter. Review-Journal staff writers Glenn Puit and John Katsilometes contributed to this report.