Progressive aphasia: when words get stuck between mind and mouth

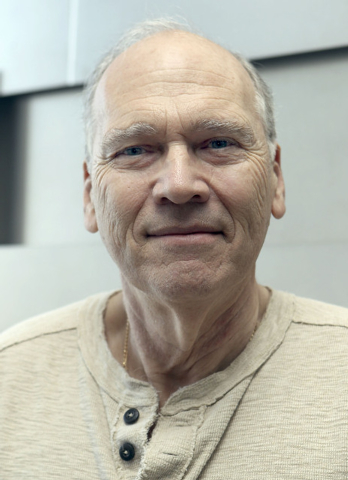

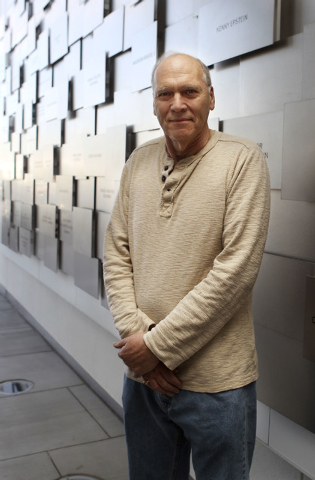

Jacob Sobotka speaks slowly, painfully. He remembers when he first started struggling for words: November 2011. But when asked his age, he can still crack a joke.

“Forty-two,” the 65-year-old says, smiling.

“You wish,” interjects his wife, Cheryl Ruley. “I wish, too!”

Sobotka, a stockbroker who still does his trade, says his thought process is intact. The problem, Ruley says, is getting the thoughts “from the head to the mouth.”

“It’s a puzzle between me and my wife,” says Sobotka, who was eventually diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

Ruley adds, “We play a lot of fill in the blanks. What’s that word? Most of the time I know where he’s going, so I can pretty much grab the right word.”

When the problems started, a stroke was suspected. Not so.

“After we found out, we really wish it had been a stroke,” Ruley says. “That would have been a lot better.”

Because of the nature of his disease, which so far affects his speech rather than memory, Sobotka couldn’t get on a trial for a certain Alzheimer’s drug that looked promising for his condition. His memory score was too high, Ruley says.

Progressive speech and language disorders, or a “progressive aphasia,” can encompass everything from having difficulties forming sentences — putting the nouns and verbs in the right places — to opening the mouth and releasing a slurred, garbled mess of sound, rather than words. Although strokes can cause similar difficulties, progressive loss over time isn’t usually associated with them. But the disintegration of speech does often accompany conditions such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, multiple sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia.

That last condition results from degeneration of the brain lobes — frontal and temporal — responsible for human characteristics such as social decorum, judgment and language, says Dr. Gabriel Leger, head of the Young-Onset and Frontotemporal Dementia program at the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health. Leger is also Sobotka’s physician.

“We think of Alzheimer’s disease as being a memory problem, but in younger individuals, language disorders can be the main manifestation of the disease, early on,” Leger says. “I think most people don’t know that.”

What might also be surprising are the prevalence and dramatically disruptive nature of speech and language problems that worsen with time, says physician David G. Lott, director of the Mayo Clinic Arizona Voice Program.

“Even for people who don’t use their voices professionally like teachers, lawyers or doctors do, when they start to have these difficulties expressing themselves, they’ll start withdrawing from life. So they stop talking on the phone. They stop going out to eat. They stop having conversations with people, because they can’t express themselves. And they lose their identity.”

An October Mayo Clinic study found that patients with a speech and language disorder are 3½ times more likely to be teachers than people with Alzheimer’s dementia. Mayo Clinic neurologist Keith Josephs, the study’s senior author, says that because teachers are constantly communicating, they may be more sensitive to the development of speech and language problems.

“When speech is impacted, we are very aware that there’s a problem,” concurs Leger. “I think the patients present to medical attention much sooner than they would if it were another kind of presentation, another part of the brain that was affected first.”

In his experience, the cause of the problem is often frontotemporal dementia or Alzheimer’s disease, at a ratio of “about 50/50.”

Historically, Leger says, a variant of frontotemporal dementia, called “primary progressive aphasia,” has been the most common cause of the speech problems. Although first described at the turn of the century, in 1906, it was so elusive that medical literature didn’t address it in detail until 1982, Leger says.

When a degenerative condition is the cause, he says, the problem doesn’t begin with the whole brain at once. Instead, it starts with an isolated part of the brain, usually critical for language, and expands into other areas.

The first cases of primary progressive aphasia described were in patients who started with speech problems but ultimately developed other issues.

Leger is careful to distinguish between the symptoms of Alzheimer’s and dementia and the “tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon” — when one can’t find the right word. “Tip of the tongue” accompanies the lessening efficiency of the brain in grabbing information, with age. Drugs, poor sleep, anxiety and stressful situations can all influence it, Leger says.

Sometimes what causes a problem and how, or if, it will progress, remain a mystery. Lott checks the patient’s voice box, tongue and the complex mechanism of human speech, to see if vocal cords aren’t working on one side — or if a patient has had a stroke that affects one side of the body. He may recruit his neurology partners to take a look, as in the case of a woman who came to him able only to grunt and make sounds.

“You’d give her a piece of paper and she’d express herself beautifully,” says Lott, adding that some people may even lose their speech because of a traumatic experience.

Neurologists haven’t uncovered what caused his patient’s plight, but he doesn’t attribute it to trauma.

Medications can help Alzheimer’s patients speech, but those same medications don’t do much for frontotemporal dementia, Leger says. But, he says, speech pathologists can make a difference.

Lott agrees.

“You may not get them back to the point where they were,” Lott says. “But you can always help people improve function.”

Jill Pichette, a speech therapist and manager of therapy services at Valley Hospital, says progressive speech difficulties can present as everything from muscle weakness to trouble coordinating movements. Her work runs the gamut from addressing posture and breathing to computerized systems.

“You may want to prepare the family at some point to know that they’re going to need another system in place to supplement speech when it becomes too difficult to understand,” she says.

Sobotka seems indifferent to the idea that speech therapy helps. But he shows off a special medication patch under his shirt, prescribed by Leger. That helps.

“We’ll be happy to stay on a level line,” Ruley says. “But eventually, it’s going to go downhill.”