Reno artist, educator finds ways to aid troubled children

RENO

For years now, artist and educator Joseph Galata’s daily rounds have included some pretty disparate places — classrooms, community theaters, broadcast booths and county social services offices – all in the pursuit of a highly emotional and personal goal.

He wants to empower the kids he believes society has abandoned: homeless gay teens, disabled kids, child veterans of the foster care system, even youths from otherwise good homes who make bad decisions.

What he offers aren’t handouts or two-bit pep talks, but a well-honed philosophy that a personal expression via the arts — dance, theater or, really, anything — can help a troubled teenager find his or her own identity in a world that doesn’t seem to care.

HIS ORGANIZATION

At 63, Galata runs the nonprofit Sierra Association of Foster Families, where clients cite his altruism and passion, and where many teenagers are amazed how someone old enough to be their grandfather so thoroughly gets them.

Galata says those mistreated foster kids bring out his paternal instincts.

“If you asked a bunch of innocent first-graders carrying their Batman lunch boxes what they wanted to be when they grew up, none of them would say a street prostitute or crack addict,” he says. “But many do. They become victims; they’re easy to throw away. To help save them, you have to find the right button inside them, to let them know they’re valuable, creative and intelligent.”

ARTISTIC ENDEVOURS

The galaxy of Galata’s artistic programs seems overwhelming, with most performances either written, performed or attended by economically disadvantaged teens across northern Nevada.

Under his guidance, youths performed anti-drug and gang dances on a national tour. There have been plays about school bullying, abandoned children and one Galata wrote called “The Boy in the Gas Chamber” about a real-life youth put to death in Nevada in 1944, which was performed for Nevada’s first lady, Kathleen Teipner Sandoval.

There is the student-inspired radio show called “Spotlight on Youth,” a program to inspire kids to help save a troubled local cemetery and a poignant play about grandparents who grieve over the struggles of their children’s children.

In that production, Galata himself performs a sad, solitary dance in honor of his grandmother, Lottie Slaney, who took him in from an impoverished home in Pennsylvania’s hill country and taught him a hard-earned lesson in never giving up.

“She was the most generous woman on Earth,” he says. “She raised me. She’s in me.”

And so the dance is for Lottie. As Galata moves across the stage, audience members are encouraged to bring up pictures of their own grandmothers.

NOT ‘WASTING A PENNY’

For Galata, helping troubled teens often means taking on the adult system set up for their care. During a visit at the Washoe County Office of Social Services to strategize with Tom Murtha, a county education liaison, Murtha tells a story about Galata’s tenacity.

A few years ago, he took over a troubled youth tutoring program in which long-term instructors never left the office, requiring kids without transportation to get to them.

On his first day, Galata let the staff know he meant business.

“I fired all 14 of them,” he recalls, explaining how he replaced them with college students. “I don’t believe in wasting a penny. The staff was irate, complaining about needing the money and their husband’s hemorrhoids. I didn’t care.”

Just listen to him: Galata breathes a blizzard of statistics, his arguments peppered with numbers used to illustrate the dire conditions of today’s troubled youth.

Here’s one: Most foster children are two to four grade levels behind their classmates, and only 3 percent attend college. And another: 56 percent of youths who leave the foster care system at 18 become homeless. And: 70 percent of state prison inmates are former foster kids.

Galata knows the importance of reaching kids early, before bad habits become ingrained for life.

I CAN DO ANYTHING

And he gets through to some — like once-troubled Lisa Etcheverry.

Now 31, she once enrolled in a program called “I Can Do Anything” charter high school, where she took Galata’s inspirational course, “Creative Combustion.”

There she learned how to release emotions through art, lessons that included breathing exercises, meditation and a regular open forum for youths to talk about their lives.

She calls Galata a ray of light in her dark, depressed teenage life.

“I came from a good home, but I was just going down the wrong path — smoking, ditching school,” recalls Etcheverry, who now manages a pair of Reno clothing stores.

“He brought out the best in me. With Joseph, I wasn’t just some kid. I mattered.”

GRANDPARENTS HIS LIFELINE

Joseph Galata came from poverty. His father was a junkman in a crumbling steel town, his family uneducated. A sewage ditch ran through his backyard.

As a boy, he went to live with his grandparents, who he says saved his life.

His grandfather had lost both legs to diabetes, and Galata recalls sitting on his lap, gazing out at the nearby graveyard, the old man telling stories about ghosts and the dead.

But it was his grandmother, Lottie Slaney, who taught him the most. An orphaned dancer who grew up on the streets of Boston, she eventually worked three jobs to care for her amputee husband.

It was Lottie who encouraged him to get involved in the theater — a place where Galata thrived, a place where he found himself.

TEACHING DANCE IN ISRAEL

Once, while teaching dance to children at an Israeli kibbutz, Galata met some aging boiler room workers at the center who had survived the Holocaust, but who had never told their stories to their children or grandchildren.

So Galata had an idea. His students’ first recital shocked the community.

“People expected a cute ballet performance,” he said. “Instead, they heard powerful, never-told stories from the Holocaust, recited by the children themselves.”

Galata later returned to the U.S., where he formed a dance theater company for Native Americans on a reservation in Washington state. In 1983, he moved to Reno, where he began developing programs for youths.

Critics say Galata’s work is too outside-the-box, too “feely-touchy” to have much of an effect in the lives of depressed kids. Yet former students call or email to tell him how much he made a difference.

His nonprofit struggles for money. While most Nevadans donate to big-name charities, the little guy like Galata is left to fight for the scraps, supporters say.

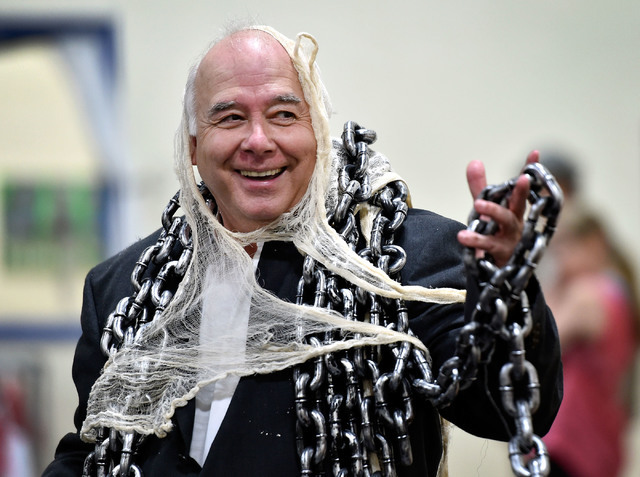

‘AN ELF ON CRACK’

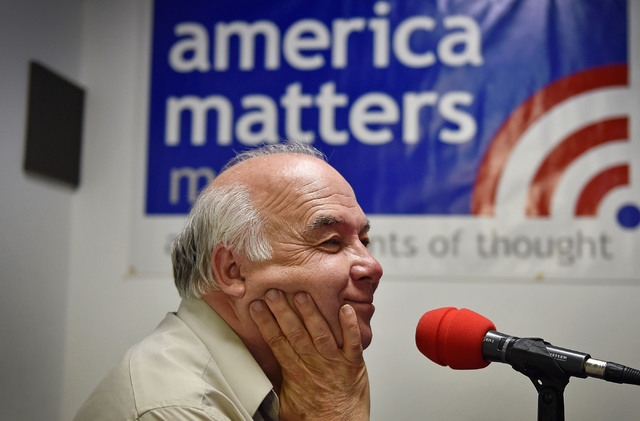

It’s a weekday afternoon and Galata sits in the same Reno studio where his students have taken on social issues for their Spotlight Youth Radio Theater Project.

On this day, though, for a one-hour program, he talks with three high school drama teachers about their motivations to become youth mentors.

At one point, he asks, “Have you ever had a student who has made you say: ‘You are on a path of self-destruction; come into my theater?’”

Galata has known such a teen; a Vietnamese-American foster-home castoff with a serious heroin habit. He invited him into his arts program, saying that anyone with such a death wish had to have some raging creativity somewhere inside him.

Years later, the former student now works as a successful costume designer. “He was a kid with one foot in the grave,” Galata says. “I’m so proud of him.”

Not every intervention succeeds. Years ago, Galata took a troubled teen into his own home as a foster parent. The youth eventually fled, and Galata hasn’t heard from him in years, an outcome that saddens him.

But he carries on. Earlier that day, Galata wanders the local Hillside Cemetery, Reno’s oldest, where he has inspired teens to protect the century-old tombstones of the people buried there.

In recent years, students from a fraternity house began parking their cars on a row of pauper’s graves, leaving behind beer and whisky bottles from parties thrown there.

“This is our community. I thought ‘How can we teach respect for that?’” Galata says. “But these mostly troubled kids have become invested in saving this place. They’re learning how to be part of the society.”

A drama teacher at the radio show called Galata the real deal.

“He’s like an elf on crack,” said actress Evonne Kezios. “He’s full of love and talent and empathy for these foster kids.”

At one Galata production, developmentally disabled teens danced onstage, laughing, lost in themselves and in the arts.

“I saw that,” recalls Kezios, “and I told myself ‘I want to hitch my wagon to this guy.’”

Later, Galata meets at a nearby performance space with a few proteges, including 14-year-old Logan Strand, who co-starred in a recent performance that dealt with school bullying, playing a kid who ruthlessly picked on his classmates.

In a powerful monologue, his character expresses his frustration and anger over his alcoholic father, offering a clue to the sphinx that inhabits a bully’s psyche.

“I never would have imagined that I would fight to hold back tears while sitting in a small community theater,” Galata later wrote. “I left asking myself the haunting question: ‘How did that kid learn to do that?’”

Strand is a quiet boy who talks in faltering sentences about embodying a violence beyond his own world.

Galata stands in the background, gazing fondly at a prized student. He smiles like a shepherd proud of his flock.

Galata's inspirations

These are some of the statistics that have inspired Joseph Galata to help needy children:

Most foster children are two to four grade levels behind their classmates

3 percent of foster children attend college

56 percent of youths who leave the foster care system at 18 become homeless

70 percent of state prison inmates are former foster kids.