Chaparral senior fights to keep dream of diploma

With one swing of his fist, James “Bubba” Dukes knocks a student to the weight room floor.

Hands clenched, the Chaparral High School senior stands over the stranger, who is unconscious and convulsing. The two faced off because the brawny North Las Vegas student — at Chaparral in late March for a Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps competition — was harassing weightlifters, according to witnesses. Dukes asked him to be respectful, but the visitor called him a derogatory name and lunged at him.

“I made the wrong choice,” says Dukes, who is charged with battery and must appear in court the week before commencement.

Graduating, always a long shot for Dukes, is even more unlikely now. With less than three months to graduation, the football player hoping for an athletic scholarship is short a year’s worth of credits.

He is wrung out by a year of tortuous life twists and the effort to provide for his girlfriend and daughter, born two days before his senior year started. But Dukes recommitted to finishing school after a brief stint selling drugs. He wants to graduate for the sake of his larger family, which has been on the brink of homelessness for most of the school year.

Dukes tells his five younger sisters, “If I can make it, and we all in the same house and we all going through the same stuff, you all can make it, too.” He’s in the habit of giving them each a dollar for good grades.

Now, though, Dukes probably will be kicked out of Chaparral for brawling. What to do with Dukes is problematic for principal David Wilson. An expulsion would send Dukes to behavioral school, where the focus is on correcting discipline problems, not on graduating students.

“If I put him in behavioral school, he’d be lost forever,” Wilson says of Dukes, a student he has guided and supported since becoming principal in 2011.

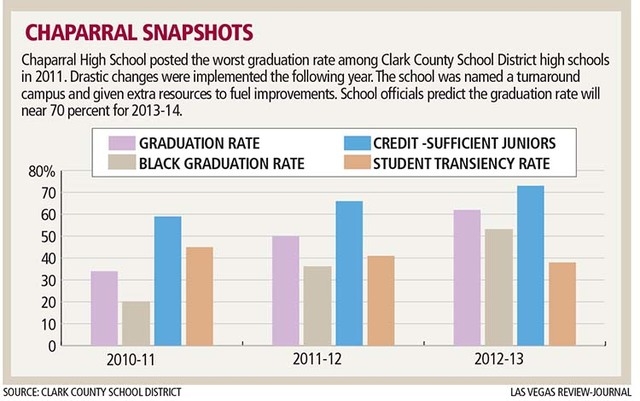

Wilson’s rule is expulsion for serious violence. One of his first acts as principal was to set a zero-tolerance policy for fighting and drugs, an attempt to change the culture at Chaparral. The school, near U.S. Highway 95 and Flamingo Road, had a history of both when Wilson arrived with a $2.5 million federal grant in one pocket and the power to replace staff members in the other. His charge: Show a significant improvement in the 34 percent graduation rate and do it by 2014.

The graduation rate has increased substantially under Wilson, but the school still struggles with students like Dukes, who face pitfalls such as truancy, drugs, criminal opportunities and their consequences.

“We have a lot of students who make bad decisions,” Wilson says.

In the case of Dukes, “that’s the example he’s had in his own life,” the principal adds.

Dukes is the oldest boy among 10 siblings — one of whom died as a toddler — raised by a single mother recently jailed for more than two months on check forgery charges. Dukes’ 73-year-old grandmother stepped in to raise his younger siblings, and is still doing so because Dukes’ mother is scarcely home after her release from jail in November.

Wilson ultimately decides to suspend Dukes for 10 days.

“If I had to put him out, that would’ve been the end of Bubba,” Wilson says. “That would’ve been the end of colleges even coming to talk to me (about him). This is my last-ditch effort.”

ABSENCES AND ASSISTANCE

After his suspension ends, Dukes is scarce at school throughout April. He gets a job at the Las Vegas Athletic Club and keeps talking about college football while skipping the classes he needs to graduate. He is still welcome at Chaparral. Wilson chooses not to flunk him for having more than 10 unexcused absences, per Clark County School District policy.

“I refuse to do that,” says Wilson, who believes students should pass if they can show mastery of the subject matter. “I’m going to take a hard look at you as a kid, and I’m going to wave my magic wand over your days and you’re going to pass. Not because I’m affronting district policy but because my kids do not have stable environments with stable parents providing them support. We are the parents.”

Wilson tracks down Dukes at the end of school April 10 and asks for an explanation of his absences. Dukes’ grandmother had a heart attack and was in the hospital for two days. He has been at home caring for his siblings.

“We were ready to scold him for not being in school this time, and here is that new perfect storm,” says Wilson, who directs teachers to take late assignments from Dukes and other students in crisis. “You take that assignment and give them credit. If they fail a test, you give them opportunity after opportunity to retake and retake that test and be successful.”

But Dukes isn’t using his opportunities, say three Communities in Schools workers sitting around a table to assist another student, a girl who doesn’t have running shoes for the track-and-field meet.

Communities in Schools site coordinator Velvette Williams offers the shoes off her feet.

“Size 9. You can run in these,” she tells the girl.

“We’ll give you the shoes off her feet,” lead site coordinator Jennifer Lopardo adds with a chuckle. “We also have a huge closet full of clothes and shoes.”

The school started a community closet in 2012-13, stocking a classroom with purses, jeans, shoes, backpacks and prom dresses. Toiletries fill a set of shelves. An assortment is stacked against the back wall, courtesy of numerous Las Vegas nonprofits. The workers usher in Dukes and tell him to take what he needs.

Since 2011, a slew of nonprofit organizations have stationed staff permanently at Chaparral. The school also has Sarah Garcia, a district social worker who provides parenting classes, diapers and baby formula to the school’s teen parents, like Dukes.

The Fulfillment Fund provides three full-time college counselors and a program to mentor college-bound students. It is doing that at just one other district campus, Del Sol High School. Project 150, a nonprofit focused on homeless youth, provides bus passes, school supplies and food for students weekly, as does Three Square, which prepares weekend food bags for Dukes’ family and others in need.

“I feel like he’s just been given so many options,” Lopardo says of Dukes. “At some point, the common denominator is him. Until he gets that, he won’t make that change.”

Dukes’ grandmother, Margaret Cole, grunts at the suggestion that Dukes missed school to take care of his siblings while she was hospitalized.

“Bubba telling a lie,” says Cole, leaning against the kitchen counter April 14, fed up and weak. She had Dukes’ girlfriend stay with the children. “Bubba stayed home because he wanted to.”

“I threw my hands up with him,” the retired social worker adds. “Flip pancakes and sweep dirt in the streets. Whatever you want to do. I don’t care anymore.”

Cole washes the children’s lunch dishes and stacks them with hard clanks.

“I done the best I can,” she says. “If there’s no effort in getting up and going to school, trying to do yourself better, that’s fine with me. Five, 10 years from now, you’re going to look up and say, ‘I wish.’ Well, ‘I wish’ will be too late.”

She looks down at her 6-year-old granddaughter, nicknamed Na Na, and asks if she has had enough to eat.

Thin and full of energy, Na Na stands at Cole’s side holding Dukes’ 7-month-old daughter, Nehemiah.

“I have seen kids in much worse shape than Bubba,” Cole adds.

Kids like 18-year-old Jessica Suarez, abandoned at age 14 by her mother. Dukes’ classmate was also behind in school, missing much of middle school to take care of her younger brothers. Her mother left them alone for up to nine months at a time before finally taking the boys to New Jersey and abandoning Suarez.

Suarez faces graduation knowing she has earned her diploma and plans to study psychology at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. She wants to be a counselor for abandoned children.

“Something I needed growing up,” explains Suarez, attributing much of her success to Chaparral and help from the Communities in Schools program.

“Anything I needed, they had it,” she says. “It made up for all the times I wasn’t taken care of.”

DOWNGRADING THE DREAM

In late April, Dukes learns that Utah’s Weber State University, Eastern Arizona College and Victor Valley College in California want him and will take a certificate of General Education Development in lieu of a diploma.

He stops coming to class entirely, forgets about finals and bets everything on passing the GED tests during summer. HELP of Southern Nevada, a local nonprofit with a Chaparral presence, offers to cover Dukes’ $95 test fee.

Wilson doesn’t want it that way and says as much to a junior college football coach. The coach asks whether Dukes can earn an adjusted diploma. The answer is no because he is short on credits.

“Next question was, can we manufacture a diploma? The answer’s no,” Wilson said. “We can’t do that. Legally, morally and ethically, I don’t have any options.”

Chaparral football coach Bill Froman doesn’t want it that way either. He tells Dukes as much in “10,000 talks.”

“Finish strong. Do a difficult task when you don’t want to. Graduate,” Froman tells Dukes.

Dukes doesn’t listen. Froman continues to support him, organizing preparation for the four-section GED test on Aug. 16.

Froman believes Dukes can pass if he tries. Dukes pledges that he will.

“I believe in my heart he means what he’s telling me,” says Froman, calling Dukes a son.

But chances are slim, and Froman knows it as he stands in the weight room on the last Friday of the school year, alone with a former Chaparral player standing tall at 6 foot 3 inches and 320 pounds.

“If you follow track records on a lot of these kids, if I played the odds, I wouldn’t be in this business,” Froman says.

The player, Will Hernandez, graduated last year and is an offensive lineman for the University of Texas, El Paso. Hernandez wanted to drop out of college, but Froman urged him on, driving 13 hours to El Paso to be at his games. Now, Hernandez has come back to lift weights with his coach and will return to El Paso in the fall for his sophomore year.

Froman sent three other players to junior colleges on football scholarships last year after catching the attention of college scouts. They didn’t make it a full semester. But Froman’s main goal at the high school level has always been clear, to the players and the other coaches.

“You will graduate. If we have to drag you by your throat across that stage, you will graduate,” sums up Chaparral’s football offensive coordinator Dave Yacabovich.

“He’s going to the NFL,” Froman predicts, smiling at Hernandez.

“It’s not the Wills who keep you up at night,” adds Yacabovich. “It’s the kid you couldn’t help. And it’s that kid who keeps you coming back.”

But Froman isn’t returning next school year. Neither are many other staffers. And neither is the federal grant money that funded efforts to turn around the troubled campus.

EXODUS

Froman decides in May to take a job at suburban Henderson’s Coronado High School. He will be the weightlifting instructor but not the football coach.

“I’m sick to death that I made the wrong decision. ‘Cause my heart is here,” says Froman, who grew up poor in Toledo, Ohio.

But his heart is also why he’s leaving. During a game last season, he was jumping and hollering at players from the sideline when his middle school son tugged at his shirt.

“Dad, Dad. Your heart. Dad, your heart,” he said, reminding Froman of his heart problem and high blood pressure.

He handed his headset to another coach and walked off the field for a moment.

Froman also has hearing problems. He has had a ringing in his ears for a decade because of Timmy “T.J.” Weber, who killed his girlfriend and her son and raped her teenage daughter. The daughter and a second son were taken in by Froman, a friend of the family, while a manhunt was launched for Weber. When Froman took the boy back to his home to retrieve some belongings, Weber hit Froman on the head with an aluminum baseball bat.

Froman doesn’t talk about it much and changes the subject as students trickle into the gymnasium for the year’s last assembly. Excited seniors, shooting selfies, take center stage in their black and orange caps and gowns.

Dukes doesn’t attend.

Wilson doesn’t know Chaparral’s graduation rate for the class of 2014 yet, but it stands to be a third consecutive year of improvement, pushing close to 70 percent. The principal focuses on the raw number: 364 graduates.

That’s more than ever in recent history, more than the 277 graduates of 2011, before turnaround plans were initiated.

“Every one of them has a story, and every one of them has a challenge,” Wilson says of the successful seniors and those who failed.

But Dukes’ situation crystallizes something for the Chaparral principal. The school will never equal the suburban schools that have graduation rates of 90 percent or better despite the lofty goals of the federal No Child Left Behind Act, which mandated in 2001 that all schools have 100 percent of their students proficient in key subjects by 2014.

Those at the core of Chaparral’s hard-fought gains worry about the expiration of the school’s $2.5 million federal grant. Will it stymie progress and prompt Wilson to leave? He has met his three-year commitment to put the school on the right track.

Despite the uncertainties, less than 10 percent of Chaparral’s 110 teachers plan to depart once 2013-14 concludes, half the national average for teacher turnover rates at all schools.

“The fact that they’re not jumping ship says they bought in,” Wilson says of the teachers.

But the expense of Chaparral attendance specialist Loretta Tucker no longer can be afforded. Wilson “surpluses” her, meaning she must find a similar position at another school or be unemployed.

Sarah Garcia, the social worker who has helped Dukes and other troubled students, will be gone after the 2014-15 school year. That grant also expires for Chaparral and seven other high schools. Most of the other social services and nonprofits plan to remain in place at no charge. Wilson earmarks $60,000 to keep two Communities in Schools staffers on campus after Chaparral’s three-year turnaround ends.

Wilson hears on June 19 that he will be leaving Chaparral to become the district’s assistant chief student achievement officer for rural schools. He hoped to see assistant principal Ramona Esparza take the helm at Chaparral, but Clark County School District administrators make her principal at Valley High School to launch its turnaround plan.

“I’m worried for Chaparral, and rightfully so,” Wilson says. “You see schools screwed up by leadership. You want strong people who get it. To me, it’s scary.”

PLANS AND PORTENTS

Wilson worries for Dukes, who doesn’t approach him at Chaparral’s June 10 graduation. Dukes racked up at least 70 unexcused absences during the 180 days of his senior year. He is not answering phone calls or texts from Chaparral staffers.

Dukes’ mother is gone, unable to return home because of three active warrants on probation violations. To settle her bad check cases, she promised to do a lot of things. Keep a job. Pay the Palms casino for the amount of a forged check she cashed there. Pay her bad check fines to Henderson through community service worth $10 an hour. She didn’t follow through.

Her son has caught a break though. Wilson is heartened to learn the battery charges against Dukes have been dismissed, which allows him to focus on earning his GED certificate. Still, Wilson worries.

“Unfortunately, I’m a realist,” he says. “You walk into my office and my walls are covered with data. Dad used to call it being a behaviorist. You look at a pattern of past behavior to predict future behavior.”

He counts the bad signs. Dukes didn’t earn a diploma. He isn’t seeking gainful employment. He sometimes works outside the law.

“If we’re looking at it from a behaviorist point of view, two years from now I see him being incarcerated,” says Wilson, tears in his eyes. “And it breaks my heart because he’s a good man.”

High school over, Dukes continues working part-time at a local gym. He takes the bus most Tuesday and Thursday nights to a GED class, sometimes attending an extra class on Saturdays.

Froman calls often to check on him. Tucker stops by every few days. Dukes stays in touch with the three college football coaches who want him after he passes the four-part GED test. The Victor Valley College coach offers to drive from California to Las Vegas and pick him up.

“I praying every day,” says Dukes, sitting on the family couch with his 10-month-old daughter bouncing on his leg.

Dukes’ 6-year-old sister, Na Na, grabs her baby niece and stands her on the laminate floor.

“I like to watch her a lot,” says Na Na, who wants to skip kindergarten next year and start first grade. She already knows the alphabet. “Want to hear me sing my ABCs, Bubba?”

“I already heard them 20 times,” replies Dukes, smiling.

He wishes he had graduated. He knows why he didn’t.

“There were a thousand reasons.”

Contact Trevon Milliard at tmilliard@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0279. Follow @TrevonMilliard on Twitter.

BUBBA’S STORY

As a Chaparral High School junior, James "Bubba" Dukes was a promising football player buffeted by personal crises as he fought to fulfill his potential.

The story of the student and the school is chronicled in a three-part Las Vegas Review-Journal series.

Part 1: As a senior, his battle to graduate intensifies, mirroring Chaparral’s own struggle to help students like Dukes succeed.

Part 2: Many hands offer help to the Chaparral High School senior, a teen father reaching for a diploma that’s his key to a football scholarship and his stepping stone out of poverty.

Part 3: Graduating, always a long shot for Dukes, becomes even more unlikely. With less than three months to graduation, the football player hoping for an athletic scholarship is still short a year’s worth of credits.

Also, see this photo feature with images taken in 2012: