Costs mount amid flurry of lawsuits over Las Vegas charter school

On the surface, Quest Preparatory Academy in northwest Las Vegas is just another school trying to improve the academic achievement of its largely low-income and ethnically diverse student body.

In one classroom during a recent visit, first-graders locked in a reading competition squealed with delight when a teammate correctly read a word. In another, a mentor brought in to provide support and guidance to the school’s staff debriefed a teacher.

But behind such routine trappings of school life, a legal battle is raging over the past and future of the state-sponsored charter school.

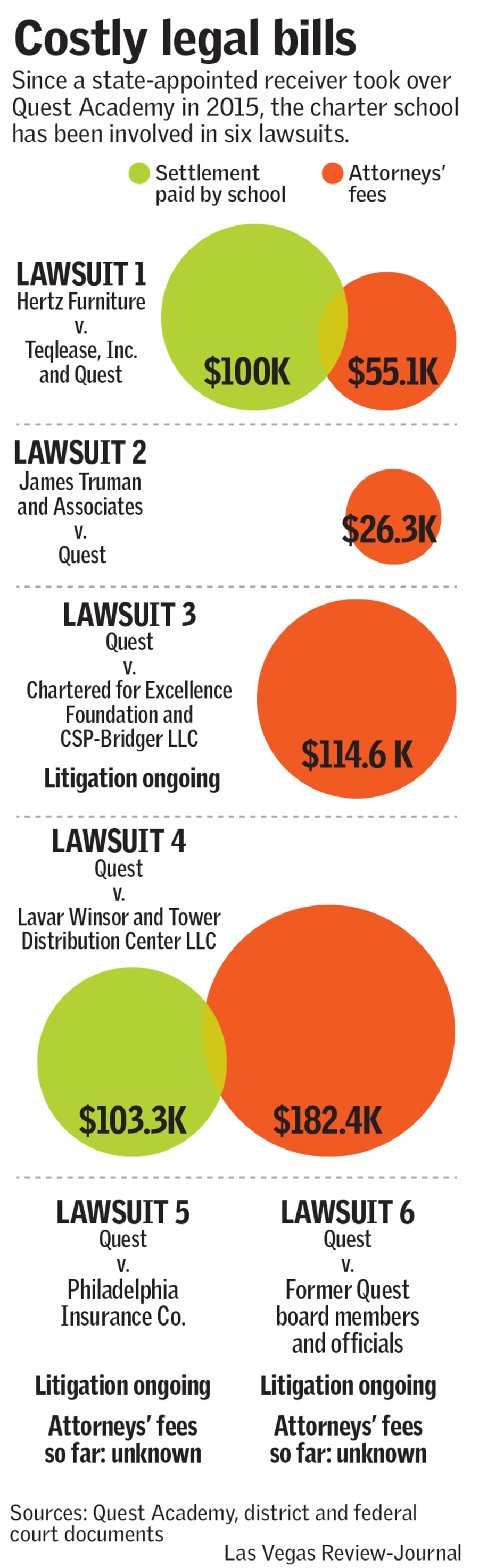

Joshua Kern, the receiver appointed to take over the school in 2015 after an audit detailed conflicts of interest and costly contracts at Quest, has sued former operators and contractors, and been sued by them in return. All told, he has been embroiled in six separate cases.

More than half a million dollars in settlements and attorney’s fees later, he is still fighting to get the school onto sound financial footing, even as it makes encouraging academic gains. He has closed two campuses and relocated a third, cutting the roughly 1,200 students enrolled at four locations to just about 500 students across two campuses in grades K-8.

Records requested by the Review-Journal show that the school has paid $581,715 in settlements and attorney’s fees so far in the cases. But Quest attorneys argue it could have been worse, saying they’ve saved the school about $2 million.

The lawsuits, Kern says, were necessary to try to recover money misspent by the previous administration and to clean up their other financial messes.

“It’s not like you’re choosing three options, one of which is great and one of which is terrible,” Kern said. “What you’re trying to do is make the best of a difficult situation.”

Meanwhile, the school’s former officials accuse Kern of dragging down Quest’s academic status and filing frivolous lawsuits.

Kern has “demonstrated a remarkable ability to engage in creative defamation through various lawsuits,” an attorney for one ex-governing board member wrote in a court filing last year, “while simultaneously bringing Quest (to) financial ruin and reducing its four-star rating down to a single star.”

Tangle of litigation

The appointment of a receiver for Quest followed a 2015 forensic audit commissioned by the State Public Charter School Authority, which detailed conflicts of interest and unnecessarily costly contracts at Quest.

It found the Chartered for Excellence Foundation, which contracted with Quest, was created by employees and governing board members of the school. The foundation then subleased property for the school’s Bridger campus to Quest for $14,771 more per month than it paid.

The audit also alleged that David Olive, the governing board’s president, used his influence to get Quest to hire family members.

Kern, a partner in the TenSquare educational consulting group, said Quest was financially insolvent when he took over as receiver and began working with vendors to reconcile the books.

But he soon found himself in court:

— Hertz Furniture sued the school, alleging it had not been paid for furniture delivered before the state took over the school, according to Quest attorneys. The school settled the case for $100,000 and paid $55,121 in attorney’s fees.

— Next the school’s former legal counsel, James Truman, sued Quest for $35,847 in unpaid attorney fees. Quest filed a counterclaim alleging malpractice by Truman. Both parties ultimately dismissed their claims, but it still cost the school $26,282 in legal fees.

— Quest then went on the offensive, suing the Chartered for Excellence Foundation and the landlord of the Bridger property, CSP-Bridger LLC.

The school claims in its lawsuit that the latter was part of a scheme to overcharge Quest for the Bridger Campus, which was closed at the end of last year. The sublease absorbed more than 60 percent of the revenue generated by the campus, far above the 10 to 15 percent threshold typical for charter schools, according to the complaint.

That lawsuit has cost the school $114,598 in legal fees and is still ongoing.

— The school later sued Lavar Winsor, a board member and officer of the Chartered for Excellence Foundation and the Tower Distribution Center company. The complaint alleged that they charged Quest $263,431 more than they paid for portable classrooms at the school’s Torrey Pines campus.

Winsor, the lawsuit claimed, used his influence as a member of the foundation to get Quest to enter into the unnecessarily expensive deal. The lawsuit claims Winsor was a manager and member of Tower, which sought over $2 million in rent payments. Quest attorneys say they reduced that figure to $103,306.

The Torrey Pines campus also was closed as Quest opened its current Northwest campus, where it is paying $192,000 less than it was for twice the space, according to Kern.

Two more lawsuits are ongoing:

— The school also sued its insurer, Philadelphia Insurance Co., over denial of coverage for financial losses suffered since the school entered receivership.

— Quest’s sixth and most recent lawsuit alleges that David Olive, Kelli Miller, Anthony Barney and Debra Roberson — all governing board members or Quest officials — breached their fiduciary duty to the school.

Kern said much of the money used to pay for the litigation came from renegotiating contacts that are better for the school. In the future, he hopes to recommend a new governing board to the state charter authority.

“In the circumstance of Quest, I believed then and believe now that this was a school that was worth trying to save,” he said. “That’s because of the strong demand, because of the type of students that Quest serves, because of how long it had been in operation and because it had pieces that could be built upon.”

Former school officials fire back

In court filings, the former school officials claim there are a gross misstatement of facts in the litigation initiated by Quest, citing a Nevada Ethics Commission opinion that concluded that Olive, the former board president, did not seek or accept any favors while in the post.

“The evidence did not establish that Olive asked or influenced (Quest’s superintendent) to hire his family members or that his family members received any preferential treatment or were subjected to different hiring standards than other applicants,” the commission wrote.

Attorneys for the former school officials also argue that many of the claims in the lawsuit cannot be pursued because they occurred outside the state’s statute of limitations.

Another court filing describes governing board member Anthony Barney as an unpaid volunteer during his tenure who was wrongly targeted in the legal battle.

“He was a parent volunteering at his daughters’ school and striving to help charter schools in Nevada,” the filing states. “The fanciful allusions to sinister activities of the Quest Governing Board should have died with the conclusions in the Nevada Ethics Commission opinion.”

Kern is engaged in a “desperate slander against good people because his time as ‘receiver has been full of educational failures, accounting gimmicks and nonstop litigation,” the filing states. “Ultimately, what has happened with Quest is a travesty, but it is in large part due to the actions of plaintiff, who now seeks to blame everyone but himself.”

Kern denied that the litigation is frivolous, pointing to the 2015 audit that highlighted mismanagement.

Improving academics

Far away from the courtroom, Quest Principal Janelle Veith keeps her focus on the classroom.

Quest was a four-star elementary school and three-star middle school in the state’s 2013-14 star ratings. Those scores declined to one star in its elementary grades and two stars in middle grades by 2016-17.

But recent results have begun to trend up.

Quest’s elementary school is 1.5 points away from achieving three stars, and its three-star middle school is outperforming three other nearby Clark County School District middle schools.

Before it closed, the Bridger campus also reached two stars.

“One thing we’re really excited about is our population that we’re serving. We’re giving them a good education,” Veith said.

“My focus is just ensuring that our school continues to improve with our academic performance, that the students have an amazing school to go to.”

Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at apak-harvey@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4630. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter.