Nevada charter schools’ successes aren’t reaching everywhere

In the 22 years since they were authorized by the Legislature, public charter schools have in some ways lived up to the idea that they could provide a better education.

For example, state-sponsored charters in Clark County — the majority of charter schools in the area — have higher “star ratings” on average than the traditional public school district as a whole.

That helps explain their growing popularity and the fact that thousands of kids in the county remain on waiting lists even though the number of charter schools has exploded in recent years.

American Preparatory Academy, for example, had over 4,000 students on its waiting list on the first day of school this year. That’s stressful for district administrative director Rachelle Hulet.

“We have a lot of amazing, amazing families that come through and tour the school and they cry and they say, ‘This would be perfect for my student,’” she said.

But by another measure, charter schools are failing to meet the mark.

A Review-Journal analysis of 2017-18 state enrollment data shows that charters serve significantly lower percentages of the most challenging students, such as those with disabilities, English language learners and those eligible to receive free or reduced-price lunches — a measure of poverty — than the Clark County School District as a whole.

The district, meanwhile, blames the growing popularity of state-sponsored charter schools as one reason for its 2017-18 deficit and for its last two years of lower-than-expected enrollment.

Now, the district is on its toes trying to compete.

“One idea that we’ve been kicking around is how can we improve customer service districtwide,” said district spokeswoman Kirsten Searer, who notes that some parents leave for charters for better customer service. “And perhaps provide trainings in areas where we’re hearing concerns from parents in the community.”

And last year, the district created a marketing position to more effectively sell its schools to parents.

When competition works

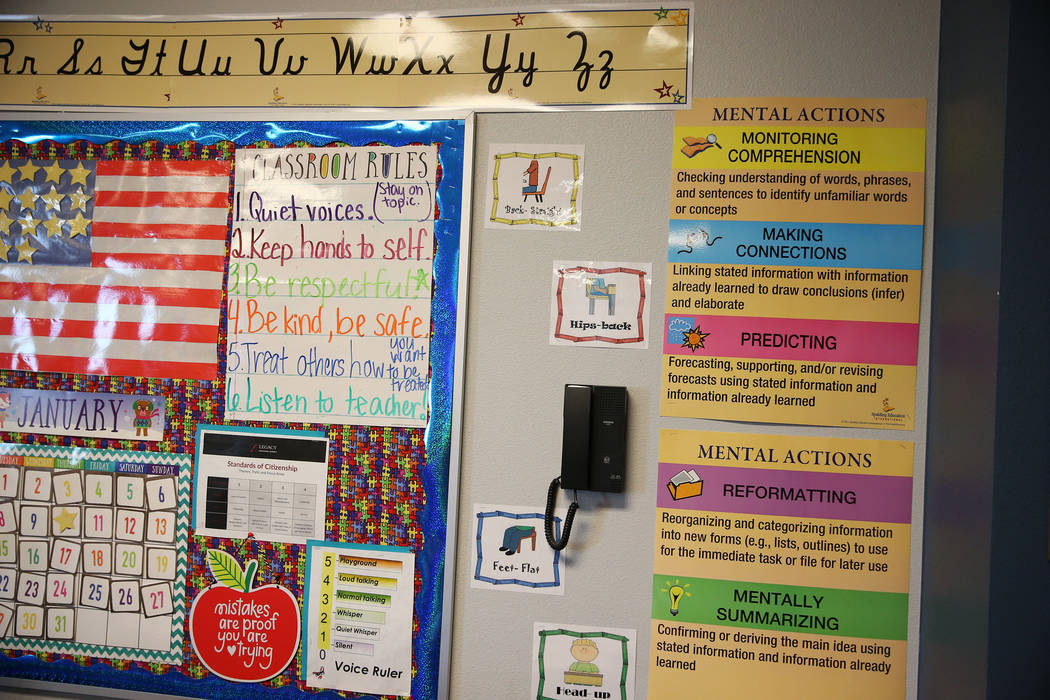

When Legacy Traditional School began construction on its first Nevada campus in North Las Vegas in 2017, Mary-Anne Ulan drove by every two weeks to show her preschool-age daughter the building where she would begin first grade.

A mere 0.3 miles away, Guy Elementary School principal Wendy Garrett braced herself for the challenge, sending out parent surveys to figure out how many students would leave.

“I knew the No. 1 thing I needed to do over here at Guy was to get our star rating up,” she said. “And that’s what we did.”

That’s the kind of competition that has long been one of supporters’ main selling points for charter schools.

When the Legacy campus opened, Ulan didn’t think twice about where she would send her daughter. She lives 40 minutes away from the charter but said the drive is well worth it.

“It’s become our family, this school,” Ulan said. “The academic excellence is wonderful, and this is our second home.”

Later this year, Legacy will have three campuses operating in the Las Vegas Valley, potentially alleviating the demand from a waiting list that stood at 132 in December.

History of growth

Charter schools in Clark County are granted their existence from one of three authorizers: the State Public Charter School Authority, the Clark County School District or the relatively new Achievement School District.

Staffed by just 17 people, the state authority has oversight of the vast majority of the charter schools operating in Nevada. The third-largest district in the state, it comprises 53 campuses with a student population that has grown from just 506 in 2005-06 to more than 42,000.

Todd Ziebarth, senior vice president of state advocacy and support for the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, said changes in state law that created the state charter authority in 2011 have been key to Nevada’s charter growth.

“I doubt you would’ve seen the growth you’re seeing there if it was just up to the local school district to authorize the schools,” he said. “I think getting that other entity in place has been key.”

The Clark County School District, meanwhile, has not added to its five charter schools since issuing a moratorium on new charters in 2010.

The Achievement School District, which began in 2017, has four schools, all in Clark County. It allows charter operators to either take over academically underperforming schools or open a new charter in the area to compete with the school.

Demographic differences

State charter officials acknowledge that they aren’t serving as many students with educational challenges as they would like.

In Clark County, they say, one obstacle is finding land for a new school in an underserved part of town. Unlike traditional public schools, charters must pay for land and facilities without aid from the state or real estate developers. As a result, schools tend to open on the outskirts of the valley in newer, more affluent communities.

“They’ve been frequently kind of in the outlying suburban areas, where land is more affordable as growth is expanding in those directions,” said Pat Hickey, executive director of the Charter School Association of Nevada. “And yet charters want to be — and arguably need to be —in East Las Vegas and other places.”

Charter Authority Chairman Jason Guinasso said the agency is working to improve outreach to underserved communities, particularly those with high percentages of poor students.

“Most families that are poor are just thinking about surviving,” he said. “So I think we’ve got to do a better job of an outreach to those families so that, No. 1, they know that the option exists.”

“We want to do better, we’ve got to do better and we are going to do better,” he said.

There may be more poor students attending charters than state numbers show, however. Many charters do not offer free or reduced-price lunch, and therefore parents may not bother to fill out an eligibility form.

Since the authority began using other methods to find students who would be eligible for free or reduced lunch, that subgroup has increased statewide from roughly 22 percent last school year to 33 percent this year.

But Guinasso still acknowledges the need for improvement.

Other challenges include finding students transportation, which most charters do not offer, and the low per-pupil funding in Nevada.

For parents, the waiting list is generally at the forefront of their minds.

Charter schools must accept students who live in the district but may give preference to certain applicants, such as siblings of current students and children of employees or governing board members. If there are more applicants than seats available, the schools hold a lottery.

Those who don’t get lucky in the lottery may be placed on a waiting list in case seats open throughout the school year. Some parents may enroll in multiple lotteries to increase their child’s chances of getting into a charter.

Financial challenges

This year, the school district paid $49 million to charters, the portion of local tax revenues that follow the students wherever they attend.

But the district also doesn’t receive the $5,781 per pupil it would have gotten for every child who enrolls in a charter, estimated at $260 million for the roughly 45,000 Clark County students enrolled in charters this year.

In addition to the financial hit, district officials say charters make it difficult to plan for the future. Although the district communicates with the authority, it pushed for a bill in 2017 to require applicants to notify the district superintendent of the proposed location of a new charter school.

The bill failed.

Searer, the district spokeswoman, also argued that the authority has never prepared an evaluation of the academic needs of an area where new charter schools may open, as state law requires.

She said another concern is students moving back and forth between traditional schools and charters, which disrupts their learning throughout the school year.

“Not only is it an issue of staffing and of budgeting, but it’s also an inconsistency in academic growth,” she said.

Parents like Charity Marshall say they understand the long-standing tensions between traditional public schools and charters but have overriding concerns.

Marshall selected Legacy for her two daughters because she thinks it’s the best fit, especially for a military family that may need to move in the future.

“I think in the end, it has to come down to what’s best for your child,” she said. “Some children might thrive and do a wonderful job in (traditional) public school. I just felt that our daughters just needed extra support.”

Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at apak-harvey@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4630. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter.

What makes charters successful?

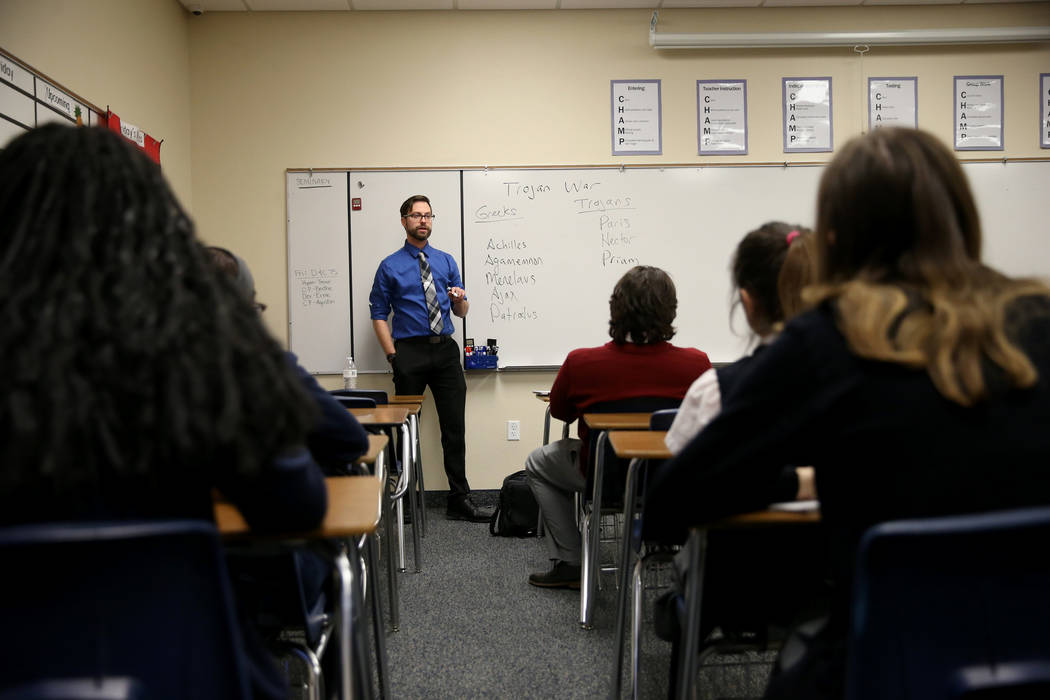

American Preparatory Academy, which began in Utah, utilizes a curriculum across all its campuses that embraces cursive, teaches Latin and ensures that students across all grades are learning the same topics.

Its lower grades are broken off into groups based on ability for reading, math and spelling.

"We do what's best for the kids," Rachelle Hulet said. "If it's best for the kids to move ahead, if it's best for the kids to go back a few lessons or to go back another group."

Its elementary and middle school are rated five stars — yet 2017-18 state data show that only 5 percent of its students had an individual education plan and 3 percent were English language learners.

But not all charters are successful.

The charter authority has been locked in a battle over accountability at two of its underperforming online charters. The school district, meanwhile, is hoping to turn the tide at its own failing charter schools, which are located primarily in underserved areas.

The School Board has recommended a shakeup in leadership at Delta Academy and 100 Academy of Excellence, and a remediation plan for Rainbow Dreams. It will revisit those recommendations at a meeting on Jan. 24.