Area vets remember Pearl Harbor, 70 years later

Even 70 years after the "date which will live in infamy," horrific memories of the Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor still burn in the minds of veterans who survived the attack.

Only a few local Pearl Harbor survivors remain to tell their stories of Dec. 7, 1941.

They were in their late-teens and early-20s at the time -- an aviator, a gunner, a cook, a mechanic, a driver, a musician. They were on board ships and stationed at military bases targeted by swarms of Japanese "Zero" fighters, "Kate" torpedo planes and "Val" dive bombers.

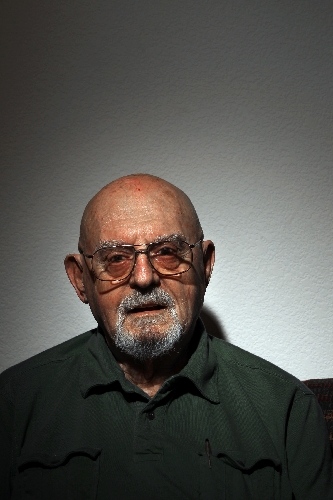

Now in their 80s and 90s, they sat in their Las Vegas living rooms last month and on previous occasions to recount their Pearl Harbor experiences.

"These people are walking carriers of history. They truly are," said Bill McWilliams, a U.S. Military Academy graduate, fighter pilot and Las Vegas author of "Sunday in Hell," a minute-by-minute account of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

"They have a unique insight to what was the first and most disastrous battle of World War II for the United States."

Pearl Harbor survivors "are a part of a generation that quite literally saved civilization in World War II," said McWilliams, a former vice commander of the fighter weapons center at Nellis Air Force Base.

"To me that's undeniable. They were there when the nation experienced a form of international treachery like no one had ever seen, and an attack with a force that no one had ever seen."

Dec. 7, 1941, changed the nation forever.

"That day pushed this nation, drove this nation into the most destructive war in human history. We literally fought almost all over the world for 44 months and 24 days at enormous cost," McWilliams said.

"It thrust the United States into what eventually became world leadership. But it also taught us something else: that you cannot stand idly by when tyrants are stalking the Earth."

At 6:05 a.m. on Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy launched the first of 350 warplanes in a 90-minute span from six aircraft carriers. There were 183 in the first wave and 167 in the second. The raid -- the pinnacle of Japan's decade-long expansionist assault that swept Manchuria from China and continued its occupation of Korea -- also involved 30 submarines. Five of them carried midget subs to infiltrate the harbor and the coast of Oahu, and other parts of the Territory of Hawaii that had been annexed by the United States in 1898.

The raid, according to McWilliams, had begun at nearby Kaneohe Bay Naval Air Station at 7:48 a.m. based on the account of a sailor in the barracks who had glanced at his watch when he heard gunfire. Eleven Japanese Zeroes strafed the tarmac, hangars and water where 30 Navy PBY-5 aircraft were parked. Japanese bombers followed in a second wave.

"They virtually destroyed the Navy's long-range patrol capability in that one strike," McWilliams said.

■ ■ ■

About the same time that Japanese fighters and bombers left their carriers on that Sunday morning, radioman-gunner Jack Leaming and pilot Dale Hilton took off in their Douglas Dauntless dive-bomber from the deck of the USS Enterprise, 200 miles west of Oahu.

They were scouting ahead of the aircraft carrier as it churned across the Pacific to join the fleet anchored in Pearl Harbor.

Leaming, from Wildwood, N.J., was one day past his 22nd birthday. Radar at the time was in its infancy, so they were flying in a squadron of 18 planes fanned out in front of the Enterprise to look over the horizon for enemy ships and aircraft. Adm. William F. "Bull" Halsey had threatened to court-martial anyone who violated his orders for radio silence.

"It was that important to him," Leaming, 91, recalled. "About an hour into the hop, we heard, 'Don't shoot. This is an American plane.' "

A few seconds later, they heard the pilot tell his radioman to get out the rubber boat because they were going in. "And that was it," Leaming said, describing the fate of the crew in one plane shot down by Japanese aircraft returning from the raid.

Of the 18 scout planes, nine were lost during the attack, including some shot down by friendly fire.

With the canopy open as they approached Oahu, Leaming could smell smoke that billowed from the devastated USS Arizona even before they could see the harbor.

They had to dodge friendly anti-aircraft fire while approaching Ford Island only to land safely at Ewa Marine Corps Air Station.

"Hilton put that damn airplane in a vertical turn for the ground, and we leveled off over the sugar cane," Leaming recalled.

Three months later, their dive bomber was hit by Japanese anti-aircraft fire. They ditched the plane in the Pacific Ocean near Marcus Island and were captured soon after Leaming inflated a rubber boat and tried to row his injured pilot ashore. Later, they were beaten up and held at prison camps. Leaming was liberated at Osaka, Japan, on Sept. 6, 1945.

■ ■ ■

Eighteen-year-old Hal LaLone, of Los Angeles, was on KP duty at Kaneohe Bay station's spud locker when he heard what he thought was a jack hammer.

"So I went out the back of the mess hall, and one of their planes dove down and opened fire on me. I took one right across the forehead, just enough to give me a sting. It hurt like hell," LaLone, 88, recalled.

He took cover in the mess hall.

"I just couldn't believe this was happening until I see the red balls on their planes," he said, referring to the rising-sun emblems on the Zeroes' fuselages and wings.

"I was watching out toward the hangars, and the guys were getting mowed down left and right," LaLone said. "I lost a lot of friends that day."

The barrage lasted seven minutes, but it seemed like seven hours "when all that's going on and you're running for your life."

For a while, LaLone hid in a walk-in refrigerator with a dozen other sailors until they realized they'd freeze to death if a bomb exploded and sealed the doors shut. So they went back outside. One of his buddies grabbed a machine gun and opened fire while bracing his back against a tree.

"He didn't last very long. They took care of him real quick," LaLone said.

■ ■ ■

Aviation mechanic Clifton Dohrmann, of Des Moines, Iowa, was asleep in the Kaneohe Bay barracks when the attack began. At 89, he is the last president of Pearl Harbor Association Silver State Chapter No. 2. He announced in November that the chapter would disband because its active members had dwindled to five, down from 41 in 2001.

Of the 20,000 U.S. military personnel who survived the attack only 2,000 to 2,500 are alive today.

After Dohrmann heard bombs exploding, he ran with another sailor for a hangar, which was their duty station. Before they reached the steel doors, a bomb exploded, sending out shrapnel.

"It split him open. I couldn't do nothing for him. I kept running," Dohrmann said.

Inside the hangar, he and some other sailors who had dodged bullets grabbed three machine guns and set them up in a semi-circle. As they fired at the attacking aircraft, the sailor next to him was hit. When the wounded sailor fell, he pulled the machine gun belt with him, jamming the gun.

Dohrmann couldn't fire any more rounds, so he dragged his wounded comrade to the ramp a short but safe distance from where Navy planes were ablaze. Parked in neat rows, they had been easy targets for Japanese aircraft that Dohrmann said came in "low and slow" and took their time destroying them.

Each parked plane had 1,700 gallons of fuel, so when bullets hit their tanks they erupted into massive fireballs that quickly reduced them to melted aluminum.

■ ■ ■

Over a ridge and southwest of Kaneohe Bay, the Army Air Corps' Hickam Field came under attack about the same time.

Ed Hall, an 18-year-old Army private from Greenwood, S.C., was scrubbing a frying pan in the mess hall shortly before 8 a.m. when he heard an explosion and then looked out the back door to see two hangars blowing up.

The next thing he knew, a Zero was flying toward him with its machine guns blazing and bullets kicking up chunks of asphalt. Just as he was ducking for cover under one of the mess hall's eaves, the pilot pulled the plane up to avoid some telephone wires. "Otherwise I wouldn't be here," Hall, now 88, said in an interview for the 69th anniversary of the attack.

After the strafing, he went to the motor pool and got a truck to recover the dead and take the wounded to a hospital.

"When you dig through the debris ... and you see a leg stick out and get the body out -- well actually wounded people still alive -- and get them over to the hospital, that's what I did the rest of the day."

■ ■ ■

On the east side of Ford Island, the USS Oklahoma was moored parallel to the USS Maryland. That's where a 20-year-old Marine private named Ray Turpin, who later lived 43 years in Las Vegas, rescued five men by pulling them through a porthole with the help of the ship's chaplain. Father Aloysius Schmitt was the first chaplain of any faith to die in World War II.

Turpin tried to persuade Schmitt to crawl out through the porthole.

"I was looking in his eyes and he said, 'I've already tried. I can't get out.' And I offered him my hand. I said, 'I'll try to pull you out,' " Turpin told the Review-Journal in December 2008, nine months before he died.

"He walked away and he said, 'I'm going to look around and see if there are any more guys that I can help get out of here.' So I waited a few minutes. He never came back. I never saw him again."

Turpin, of Waterloo, Ala., survived by scaling a 3-inch-diameter rope line that tethered the Oklahoma to the USS Maryland.

"I was hanging under it like a rat," Turpin said, describing how he was about to reach the Maryland when sailors were ordered to chop the line with a fire ax to keep the Maryland from sinking with the Oklahoma.

That sent Turpin splashing into the oil-slicked water. "I had a hard time figuring out which way was up. I finally popped up, and there was a sailor in the water who was a good swimmer. I told him I wasn't a very good swimmer. So he helped me over to the Maryland."

■ ■ ■

To the north of Hickam Field and tucked behind Ford Island, Petty Officer 1st Class Ira "Ike" Schab, a sousaphone player in the admiral's band, was getting dressed on board the USS Dobbin, a destroyer tender. He had just closed his locker when the ship's alarms sounded.

"This is no drill," he said. "I was curious and popped up to topside just in time to see the Utah capsizing."

Then, before he headed below deck to load anti-aircraft ammunition, he witnessed an iconic event.

"I was looking right at Battleship Row, right across the point of the island," he said.

"I saw the Arizona take the big one, that classic shot that we have of the Arizona being hit. ... I thought, 'Oh my God!' because I had about 40 or 50 personal friends on board."

He also saw the USS Nevada, the only battleship to get under way though severely damaged.

Schab, of Whittier, Calif., responded to the attack by loading .50-caliber bullets into machine gun belts and also lifting up 200-pound boxes of anti-aircraft projectiles from an ammo magazine through a manhole to the deck above him.

Although he was in shape from toting tubas around, lifting boxes of anti-aircraft rounds was another feat.

"That was the remarkable thing. I could take about 200 pounds with one hand and I only weighed 165. So that's adrenalin for you," he said.

The night before, Schab's band from the Dobbin had performed in the Battle of the Bands at the recreation center.

"My band took fourth place. The Arizona took second, the West Virginia took third and the California took first."

After the contest, the Arizona's captain told the Arizona's band master, "You guys have done a fabulous job.' And he says, 'I'm very proud of you. I'll tell you what. Tomorrow morning you guys can sleep in.' And that's the story. That's where they are today."

Most of the 1,177 sailors killed on the USS Arizona went down with the ship.

Schab, 91, said he went back to Hawaii in 1988 on a job assignment and came within a mile of the sunken Arizona but didn't visit the memorial "because I think I'd break down entirely."

"Emotions run pretty deep," he said, noting that few Pearl Harbor survivors who travel to Hawaii go to the Arizona Memorial. "They can't stand it. It just tears them up."

On Wednesday, the 70th anniversary of the attack, Schab will join other Pearl Harbor survivors for a private luncheon ceremony at Nellis Air Force Base. He said he'll be thinking about how lucky he is to be alive. More than 2,400 military personnel and 68 civilians were killed in the attack.

"The thing that really concerns me is the general populous is forgetting these things. They shouldn't forget them. You can forgive but you can never forget," he said. "Japan has been pretty much of an ally since then. ... I forgave the Japanese many, many, many years ago."

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.