Las Vegas judge hears over 300 petitions a week for mental health commitments in Clark County

Two days a week, Clark County Judge William Voy oversees hearings for petitions to commit people to an inpatient mental health facility for evaluation, observation and treatment.

“We’re averaging about over 150 petitions each hearing. So that’s 300-plus petitions a week,” he said.

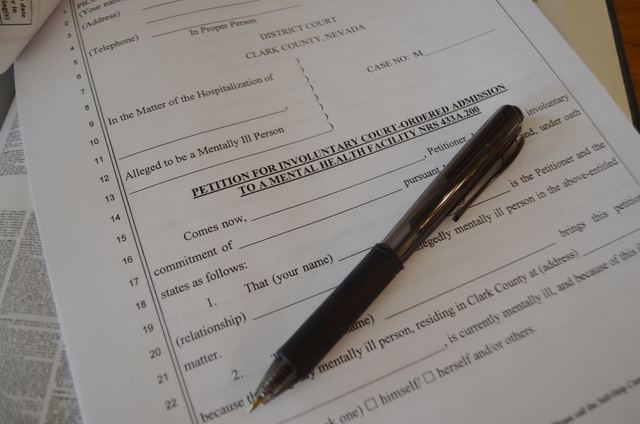

According to Nevada Revised Statute 433A, Admission to Mental Health Facilities or Programs of Community-Based or Outpatient Services; Hospitalization, there are three ways to be admitted to a mental health facility in Clark County. Potential patients can seek help voluntarily, or a petition to commit an individual — a Legal 2000 — can be made in an emergency situation by a physician, psychologist, social worker, registered nurse or by any officer authorized to make arrests in Nevada.

The court can also step in and order a commitment at the request of a close relative.

“You have to be related by marriage or blood — it’s your child, your husband, your sister, your brother, that kind of familial relationship,” Voy explained.

He added that the route one seeks for commitment depends on the situation.

“If your family member is so seriously, acutely mentally ill to the point that there’s a substantial likelihood that they may do bodily harm to themselves or others, 911 would be the first call,” Voy said.

Sandy Stamates, president of Southern Nevada’s branch of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), agreed.

“If your loved one is threatening, then you need to call the police,” she said.

Voy and Stamates advised caution when calling for law enforcement help.

“We advise our family members to let the police know that it’s a mental health situation and to ask for a Crisis Intervention Team-trained officer because they have a special 40-hour training that helps them understand mental health issues,” Stamates said. “It helps them learn to de-escalate issues.”

Lynne Bigley, supervising rights attorney for the Nevada Disability Advocacy & Law Center, also spoke highly of the Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training, a national program started in Tennessee in 1988.

“They’re just tremendously trained and talented individuals who come and are great at de-escalation techniques,” she said. “They’re very understanding about individuals in crisis and extremely helpful to families.”

Bigley said the CIT training is just one effort to make sure people with mental illness end up in treatment and not jail.

“There are efforts made to at least try to make sure the person is diverted appropriately, taken to an emergency room and put on a Legal 2000, a legal mental health hold, rather than being diverted to jail or prisons. But the reality is that there is certainly an over-incarceration of individuals with disabilities, particularly mental illness. It’s not unique to Nevada. It’s a national problem and national discussion.”

Voy said calling 911 isn’t always effective. Some people in crisis may not show symptoms during a police officer’s visit.

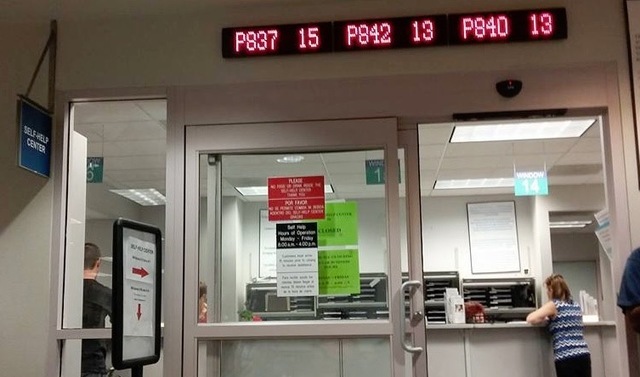

“A lot of people can do that,” he said. “They can keep it together for a 10-minute conversation with law enforcement, and then they leave and they go back to their delusional, psychotic state,” Voy said. In that situation, he recommends family members visit the Clark County Family Court, 601 N. Pecos Road, to file a petition. “You can come to the family courthouse, go to the Self-Help Center and request a civil commitment packet to fill out,” Voy said. “Follow the instructions; you don’t need a lawyer.”

The paperwork and notary services are free. Be prepared for airport-quality security and Department of Motor Vehicles-style waits. Once the paperwork is filled out, it goes upstairs to Voy’s office, where his administrative assistant reviews it, and if necessary, meets with the petitioner to get further information.

“ Then it is presented to me by her, and then I determine whether I should sign it or not. It’s a very similar process to when law enforcement would get a warrant for someone’s arrest with probable cause,” Voy said. “It’s presented to me in chambers, so I can determine whether it has probable cause, whether or not they meet the criteria for commitment, which is danger to self or others.”

Not all petitions are accepted. NRS 433A.115 dictates that a petition should be rejected if it involves a person whose “capacity is diminished by epilepsy, intellectual disability, dementia, delirium, brief periods of intoxication caused by alcohol or drugs, or dependence upon or addiction to alcohol or drugs, unless a mental illness that can be diagnosed is also present which contributes to the diminished capacity of the person.”

Once Voy approves a petition, a pickup order goes to the Metropolitan Police Department detention center. Voy said the patient is typically handcuffed for transport for their own and the officer’s safety, with a family member present.

“It looks like a normal arrest to be honest with you,” he said. “They’re not guys in white coats with straitjackets jumping out of a wagon. You only see that in the old TV movies. It’s like a normal arrest. That’s why we’re very cautious about initiating that process.”

The first stop is University Medical Center, 1800 W. Charleston Blvd., where the patient is cleared medically.

“You’re not required to have a physical, but the doctor has to confirm that the symptomatology that you are displaying isn’t due to some medical emergency like dehydration, epileptic seizure, things like that,” Voy said.

Assuming the patient clears medically, he’s taken to a triage facility, where mental health professionals can make further assessments. Voy said the center can discharge a patient without further court order if it finds that he no longer meets commitment criteria. Patients can be held for up to 72 hours.

Wednesdays and Fridays, those who are still considered eligible for commitment have their case presented in a commitment hearing at Southern Nevada Adult Mental Health Services, 6161 W. Charleston Blvd. Patients and family members are welcome to participate. Patients can also have an attorney represent them. The treating psychiatrist and court mental health professionals make presentations. If it’s determined a patient should be committed, a six-month order is signed , and he is transported to a locked mental health facility .

Voy said, typically, patients stabilize swiftly once they receive treatment and medication in triage.

“The overwhelming majority of those patients clear within days and are released,” he said.

Voy estimated that less than 20 percent of the petitions he sees result in a full involuntary commitment. Most cases are dismissed before the hearing.

That said, many patients revisit the system, stabilizing and destabilizing. To deal with the revolving door problem, the 2013 Nevada Legislature approved an outpatient commitment program to give patients resources to keep them in ongoing treatment outside mental health facilities. Voy said the program helps 80 to 85 people at a time.

“And our success rate is just phenomenal,” he said.

Stamates said as families face mental illness, it’s important to look for early warning signs and seek treatment as soon as possible. But she said that like the story of the frog tossed in water brought slowly to a boil, many don’t see a crisis coming.

“Sometimes, it’s so subtle, you don’t even realize,” she said. “Usually by the time someone is calling us, the symptoms have been going on a long time and getting progressively worse. It’s like anything else. If you’ve got diabetes coming on, it’s probably not going to get better by not addressing it. It’s probably not going to go away. It’s going to get worse. We really believe that the earlier you can get a diagnosis, the better the outcome, and isn’t that true for everything?”

The Clark County Family Court Self-Help Center is open from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday. Petitioners must pick up a number from the information desk at least 15 minutes before closing.

To access the Nevada laws about mental commitment, visit tinyurl.com/nvrs443a.

Additional resources and information are available at namisouthernnevada.org and ndalc.org.

Contact View contributing reporter Ginger Meurer at gmeurer@viewnews.com. Find her on Twitter: @gingermmm.

Upcoming Mind Matters story topics:

In September: A preview of pending state and federal legislation affecting mental health care and existing laws and policies that shape the current system in Nevada.

In October: A look at how the prison system and local law enforcement handle those with a mental health issue; also a look at how we begin to improve the mental health system in Nevada.