Las Vegas attorney tackles issues for allergy sufferers

Homa Woodrum makes a living as a guardianship attorney, but it is her work as an allergy advocate that she calls her "passion project."

In 2014, the Las Vegas attorney was one of three women who founded the Allergy Law Project, a website designed to provide accurate information about the intersection of law and food allergies. All three women have children with food allergies, and all three are lawyers.

"We all have day jobs," Woodrum said.

Woodrum, 32, was introduced to the world of allergies after giving birth to her first child, daughter Eleanor, in 2008.

As an infant, Eleanor had constant skin problems. Then at 15 months, she got her hands on her mother's toast, which was covered with Nutella hazelnut spread. After tasting some, the child quickly became upset and "was clawing at her throat," her mother said.

Woodrum gave her daughter some Benadryl and let her drift off to sleep.

"Looking back, I should have taken her to the hospital," Woodrum said during a recent interview at her law offices.

Eleanor's pediatrician later ordered a blood test and personally called Woodrum with the results: The child was allergic to tree nuts, peanuts, oats, sesame, milk, eggs, wheat, corn and soy.

The pediatrician instructed Woodrum to come to the doctor's office right away for an EpiPen, which can be used to inject epinephrine during an anaphylactic episode, and referred Eleanor to an allergist.

Woodrum, who was still breastfeeding, stopped eating everything on her daughter's allergy list. Within two days, the child was showing a new interest in eating solid foods.

"It was shocking to see how obvious it was once we knew," Eleanor's father, Adam, said.

Homa and Adam Woodrum, who met while attending UNLV's Boyd Law School, were married in 2007 and are law partners. They still kick themselves for not figuring out their daughter's problem sooner. They lived in Winnemucca for a few months after Eleanor's birth, and their doctor at the time had referred them to an allergist in Reno, but they never followed through.

"We were first-time parents, so we talked ourselves out of a lot of stuff," Homa Woodrum said.

Discovering their daughter's allergies meant major lifestyle changes for the Woodrums. Already vegetarians, they temporarily became vegans.

"We ate rice and potato chips for two years," Adam Woodrum said, only half joking.

Regular testing eventually revealed that Eleanor had outgrown some of her allergies. The 7-year-old eats soy, wheat, corn, eggs and milk.

The Woodrums' second child, 5-year-old Robert, has shown no signs of allergies.

When Eleanor was young, she had a hard time understanding why she couldn't have the same food other children were eating, such as cake at a birthday party.

The parents didn't want to tell their daughter that she could die if she ate forbidden foods, but when they explained that she could stop breathing, the child put two and two together.

Eleanor has learned to be careful about what she consumes, and she heads off to second grade every day with a pair of EpiPens zipped in pouches around her waist. She has never had to use one, although her mother probably should have once.

When Eleanor was 3 or 4, her mother left her in someone else's care for the first time. Homa Woodrum returned to find her daughter "sneezing uncontrollably" and breaking out in hives.

"She was scared; she didn't want me to use the EpiPen," Woodrum said.

Instead, the mother gave her daughter Benadryl and put her in the shower. Woodrum acknowledges she should have used the EpiPen.

"I will always be honest about what I do or don't do under stress," she said, putting on her allergy-advocate hat.

Woodrum still doesn't know what caused her daughter's reaction that day, although she suspects it was a cat.

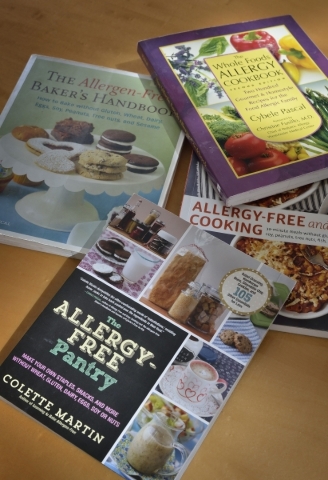

While spending time at home when her children were younger, she often read blogs. At her husband's urging, she decided to start a recipe blog for families dealing with allergies.

"I had done Web design before law school, so the tech stuff came easily," she said.

The blog's name, "Oh Mah Deehness!", was inspired by the way her daughter used to say, "Oh my goodness!" It can be found at ohmahdeehness.wordpress.com.

With the blog, Woodrum set out to answer questions such as "How do you make a loaf of bread when you can't have eggs or milk or wheat?" She later branched out into legal topics.

In August 2014, she wrote on her blog about an Amtrak policy that said unaccompanied children "may not have any life-threatening food allergies." That piece caught the attention of Maryland attorney Mary Vargas, who then sued the railroad passenger company.

The case is still pending, but Amtrak since has changed the policy.

In August 2012, Woodrum appeared before a legislative committee to speak in favor of a requirement that all Nevada schools stock auto-injectable epinephrine. The bill became law in 2013.

Last year, she traveled to Washington to lobby for mandatory disclosure of sesame in foods.

She also co-founded the Food Allergy Bloggers Conference but stepped down after the 2014 event. That year, Massachusetts attorney Laurel Francoeur came up with the idea for the Allergy Law Project and invited Woodrum and Vargas to join her in providing free information online about allergy law in the United States.

Woodrum, who also works as an adjunct professor at Boyd Law School, said allergy issues generally fall under three federal laws: the Americans With Disabilities Act, which ensures equal opportunity for people with disabilities in employment, state and local government services, public accommodations, commercial facilities and transportation; Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, which requires that children with disabilities receive equal access to an education; and the Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act.

In her role as an allergy mom, Woodrum attends what are known as "504" meetings each year at her daughter's school. The meetings typically involve an administrator, the school nurse and Eleanor's teacher. Together, they come up with a plan that allows Eleanor to have a free and fair education, which — the mother notes — includes social benefits.

Even for someone who understands the process, the meetings can be stressful.

"I shake through all of mine," Woodrum said.

Eleanor attended the most recent 504 meeting and later told her mom, "I like how everyone wants to keep me safe."

Rather than come to the meetings with a list of demands, Woodrum prefers to help her daughter's teachers come up with their own ideas.

This year, Eleanor eats her homemade meals at a separate table in the school lunchroom. She is allowed to have a friend join her, if the friend is eating a school lunch. Woodrum said she has been told that public school lunches don't contain nuts, so she believes Eleanor faces little risk from mere exposure to them.

When asked what she considered to be the worst aspect of having allergies, Eleanor answered without hesitation: "Not being able to eat what my friends eat."

She specifically mentioned Reese's peanut butter cups, although her mom said she eats Sun Cups, made from sunflower butter.

"She just wants to be like other kids," her mother said.

On a recent afternoon, Adam Woodrum brought the couple's two children to the Woodrum Law offices after school. There, the youngsters changed clothes before heading off to a tae kwon do class.

That concept of equal treatment lies at the heart of the Allergy Law Project's mission statement: "Supporting equal access and safe inclusion of individuals with food allergies under law."

— Contact reporter Carri Geer Thevenot at cgeer@reviewjournal.com or 702-384-8710. Find her on Twitter: @CarriGeer.