Six-officer team keeps the peace on Mount Charleston

Half an hour removed from urban Las Vegas, Metro police Sgt. Andy LeGrow waves at hikers and blows his horn at a ground squirrel as he drives his patrol truck down a curvy Mount Charleston road.

LeGrow leads a six-officer unit that works out of a double-wide trailer on the north side of Kyle Canyon Road, just before the Resort on Mount Charleston. There are typically only three or four officers on duty at a time, and they spend little of it in the office.

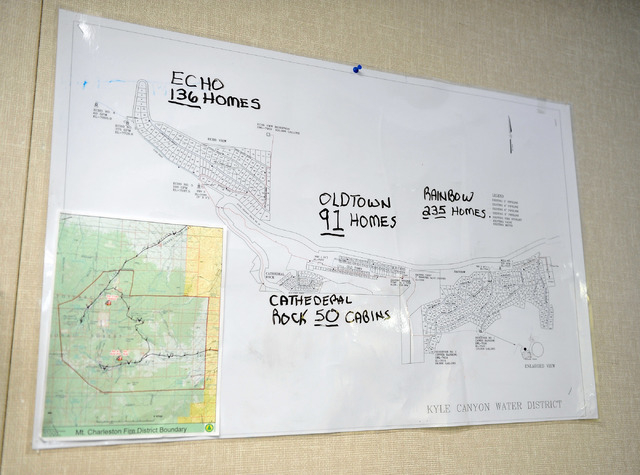

The small force patrols the mountain and Cold Creek west of U.S. Highway 95. They also patrol the Desert National Wildlife Refuge and the Sheep Mountains to the east. Indian Springs is part of their jurisdiction. They are responsible for roughly 2,000 square miles — a steep difference from the 100-square-mile section that the nearest Metro area command patrols.

As the only first responders immediately available, the unit deals with everything from mountain lion incursions at the Girl Scouts camp to car crashes, flooding and fires.

The unit evacuated the mountain of hundreds of residents last summerduring the Carpenter 1 wildfire, which grew to more than 43 square miles. Becky Grismanauskas, resident and vice chairwoman of the Mount Charleston Town Advisory Board, believes lives were saved because the officers persuaded residents inclined to stay to leave instead.

“They go that extra mile,” she said. “And some of those newer officers, they are just stepping up to the plate like they’ve been here forever.”

The Metropolitan Police Department has several other resident officer sections, which were created decades ago to serve rural areas of Clark County, including Sandy Valley, Primm and Bunkerville. Instead of a city officer having to drive an hour to respond to a 911 call, resident officers lived within those rural areas. The only place where that remains the case now is Laughlin.

Las Vegas has grown over the decades, encroaching on those once-isolated communities. It’s now barely a half-hour drive from the edge of Las Vegas to Kyle Canyon.

Metro’s northwest area command has slowly assumed responsibility for Mount Charleston and surrounding communities, integrating LeGrow’s unit. Though the unit is still the only police presence around the mountain, officers are no longer required to live in the patrol area, and a policy that paid resident officers extra salary has changed.

Initially, resident officers were paid 20 percent more on top of their annual salary because they were always on call. They often worked nights or on their days off to respond to emergencies. According to northwest area command Capt. Chris Tomaino, it was cheaper to pay them a flat rate for the year than to pay them overtime accrued gradually.

Now, however, because the rural areas are more accessible, it’s cheaper to pay the overtime. The four officers assigned to the Mount Charleston unit who got their positions when the 20 percent policy was still active will continue receiving it. Those newly transferred to the unit won’t, including LeGrow, who two years ago became the first sergeant in a resident officer section without that extra tier of pay.

The sergeant, a Metro veteran of nearly 30 years, doesn’t mind.

“I’ve had my share of that,” LeGrow said of the violence he dealt with while working as a patrol officer and in undercover vice.

There is very little traditional crime in his area now, he said, and he enjoys the change of pace. There are occasional calls about domestic conflicts on Mount Charleston and burglaries in Indian Springs. But often the situation is worked out without an arrest. A larger portion of the job is devoted to public safety and developing relationships with residents.

LeGrow likes the amount of face-to-face communication involved. Tomaino agreed that it’s a big part of being a resident officer, comparing the relatively calm, quirky community to Mayberry on “The Andy Griffith Show.”

“Everyone waves — it’s great,” LeGrow said of the residents he protects. He enjoys interacting with residents — and anyone else on the mountain. He speaks with tourists and hikers as he patrols the roads and trails. He chit-chats with Las Vegas Paving Corp. employees as they do construction work outside his substation and attends neighborhood meetings.

“How could we be so lucky?” Grismanauskas said of the officers. “They do love the residents. There’s no question. And the residents love them.”

LeGrow’s communication skills are part of why he was recommended for the job, his captain said. The small population requires more repeated personal interactions than a typical patrol position does. LeGrow and his officers are on a first-name basis with many residents.

On the flip side, LeGrow’s communication skills are necessary for his position because it’s sometimes in short supply between officers on the mountain.

Metro’s radio system is problematic, even in the valley. The department is working to upgrade it. But that problem is exacerbated in the mountains. Dense foliage and hills often block radio signals, and because the three to four officers usually on shift are often spread out, good instinct is imperative. Tomaino commended the Mount Charleston unit on following individual gut instincts and training when responding to incidents in areas with spotty signal coverage.

Coordination is key with everything, LeGrow said, whether it be his own officers, Metro officers in the valley, residents, forest agencies or emergency services.

“We take a deep breath, regroup, and deal with whatever it is,” he said. “I haven’t had anything really too far off the norm. But the day isn’t over yet.”

Contact reporter Annalise Little at alittle@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0391. Find her on Twitter: @annalisemlittle.