Park worker’s death prompts changes at Death Valley

More than a year after a National Park Service road worker died alone in the heat of Death Valley, agency officials have finished their investigation and rolled out new safety measures for one of the world’s most unforgiving workplaces.

Death Valley National Park safety manager Paul Treuherz said improvements have been made to park training procedures and communication protocols, including the mandated use of satellite phones and panic buttons by employees working in remote corners of the 3.3 million acre park 100 miles west of Las Vegas.

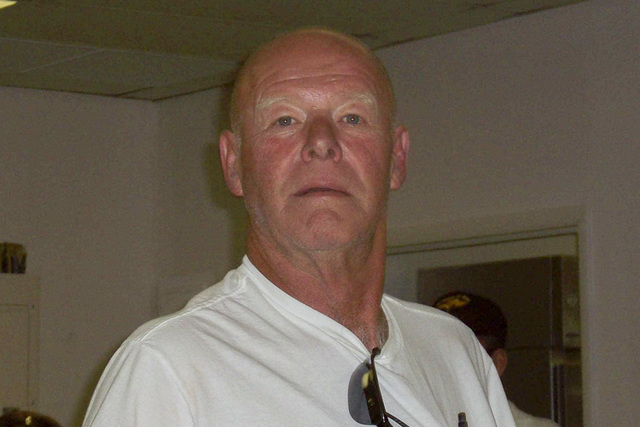

Better communication could have saved Chuck Caha, who died from heat stroke Sept. 19, 2013, after a tire went flat on his road grader and he tried to walk roughly five miles back to his pickup in temperatures well over 100 degrees.

The 64-year-old Pahrump man was working by himself in a part of the park that was closed to visitors after flash flooding earlier in the summer. No one went looking for him until he failed to return to the maintenance yard at the end of his shift.

Caha’s family was briefed Thursday on the results of the Park Service investigation.

His son, Jeff, said nothing they were told changed his mind about what happened.

He still doesn’t blame his father’s coworkers or the Park Service at large. There were some “stupid failures of common sense,” he said, but no major negligence.

Mostly, it was a lot of little things that went wrong that day — minor setbacks and small mistakes that turned catastrophic in the triple-digit heat.

Caha had a radio with him, but the battery was dead.

He was supposed to be paired with another employee, but that man had a family emergency and couldn’t come to work.

Jeff Caha said his dad could have driven the grader out on its flat tire, but he wouldn’t have wanted to damage the machine. He could have sheltered in the grader’s air-conditioned cab until someone came looking for him, but he wouldn’t have wanted to get paid for sitting around doing nothing.

“He just didn’t do what he was supposed to do,” Jeff Caha said by phone from his home in New Mexico. “It drives me nuts.”

A separate investigation by the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration revealed five serious workplace safety violations by the park. They included sending workers into remote areas without working radios or other means to call for help; not checking on employees working alone in dangerous weather conditions; failing to properly train and equip staff members to work in extreme heat; and failing to properly train workers on what to do in unexpected situations such as an injury or a vehicle breakdown.

The violations were outlined in a “Notice of Unsafe or Unhealthful Working Conditions” sent to the park in March.

The OSHA investigation remains “open and ongoing,” according to a letter from the agency’s San Diego area office, which was sent to the Review-Journal in response to a request for records under the Freedom of Information Act.

It’s unclear when the investigation will be closed.

Park officials consider that a formality since the violations have all been addressed.

“We fixed them as quickly as we could,” Treuherz said.

The biggest changes came in the area of communication.

Before Caha died, Treuherz said the park kept a handful of satellite phones for workers who felt like carrying one. Now they have enough for everyone, and employees are required to take one whenever they venture into the back country so they can check in at regular intervals.

Workers also are equipped with GPS trackers that can send out an alert and a location when triggered. Before they leave, they have to file travel plans detailing where they are headed and when they will be checking in.

Treuherz said Caha’s radio was working but its charge was low when he left the maintenance yard on the morning of his death. All park vehicles now carry internal radios, and employees have been given extra chargers so they can plug in their handheld units at work and at home.

Caha’s death also revealed gaps in the park’s employee training program. Visitors are supplied with brochures and other material instructing them to stay with their vehicles if they get stranded in Death Valley, but that advice was not part of the formal training for employees.

“It was more of a word-of-mouth sort of thing,” Treuherz said. “That’s where the park failed a little bit.”

As for the heat-stress protocols for employees, Treuherz said the park was in the midst of a review by the Center for Disease Control’s National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health at the time of Caha’s death. The review, completed last June, revealed that conditions at Death Valley “were often above limits for heat stress at work” and that employees did not always follow the park’s policies for working in extreme temperatures.

Changes made since then include providing workers with thermometers and body temperature monitors, Treuherz said.

“We’re giving people better tools to monitor where they’re working and their own physical condition,” he said.

Of course, none of this means much to Jeff Caha, who can’t shake the thought of his father lying out there on that road.

“I’m happy no one else is going to die. It does nothing for me,” he said. “My dad’s not coming back.”

Contact Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350. Follow @RefriedBrean on Twitter.