Former commissioner believes she went to prison for a reason

For two years, Mary Kincaid-Chauncey's schedule was set: Wake up at 5:30 a.m., work three shifts wiping down tables or cleaning toilets, and spend her down time exercising and reading the Bible.

For the former public official who spent nearly three decades in office, there were no more meetings, no more briefings, no more early morning calls from constituents. Instead, she performed menial jobs, earning 12 cents an hour, while she worked at a federal prison camp in Victorville, Calif.

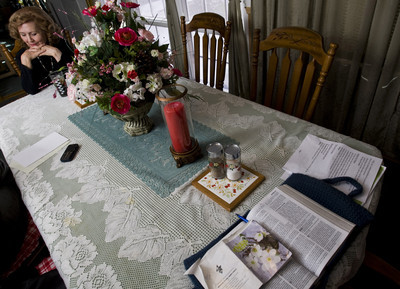

At her North Las Vegas home on Friday, having just signed her release papers from a halfway house in downtown Las Vegas, the 70-year-old recalled the day she parted with her family, including husband Bob Chauncey, and entered the minimum-security facility 220 miles from Las Vegas.

She was forbidden from bringing anything into the prison: no photographs, not even her wedding ring.

She cried when she was fingerprinted, and again when she was strip-searched.

She cried for two weeks straight.

She fretted she wouldn't be able to defend herself if she was attacked.

"I was scared. I was homesick. I thought, 'Why did this happen to me?' Then I finally said, 'I can sit in here and ask why and have a pity party, or I can make the most of it.'"

She believes she served time for a purpose. God had a reason, perhaps a message for her to spread.

"Most of the women had no religious background," said Kincaid-Chauncey, who started a Bible study class that grew over time.

"The only reference to God they heard was attached to a swear word."

Until the end of her term late last year, Kincaid-Chauncey was the oldest inmate at the camp that houses an average of 300 women. She reached out to the narcotics dealers and smugglers who made up about 80 percent of the prison's population.

She heard about how they grew up in drug-filled homes, often without parents who themselves were serving time.

"I learned a lot, not all of which I wanted to learn. All these kids would come in to visit (their mothers) and cry. I couldn't help wondering, 'Are we just perpetuating this problem?'"

She said she will never look the same way at a drug addict or homeless person.

"I could see the hurt they suffered, the hurt they went through. It was eye-opening. I think I will think more deeply about what's going on in their lives. It's much more personal now. Much more personal."

MAINTAINING HER INNOCENCE

Kincaid-Chauncey maintains her innocence. She said she never took one illegal cent from strip club owner Michael Galardi, even though in 2006 a jury found her guilty of accepting bribes and failing to provide honest services to Clark County residents.

She believes she would have been acquitted had she been tried separately from former colleague Dario Herrera, who also was found guilty and whose sexual exploits and extramarital affairs irked jurors. After the eight-week trial, jurors said they spent most of their deliberations on Kincaid-Chauncey.

"I had a real sinking feeling" Kincaid-Chauncey said, recalling her emotions when teary-eyed jurors entered the courtroom to announce their verdict. "I watched the jurors during the trial and thought nothing could convince them I wasn't guilty."

Kincaid-Chauncey doesn't have a job. She sold her North Las Vegas flower shop to a relative to pay off $19,000 in court-ordered restitution. Although a 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals panel recently upheld the jury's conviction, she plans to continue contesting her case. She intends to clear her name and regain the right to vote.

She has no desire to return to politics, although she embraces the idea of becoming an advocate for imprisoned women.

ON THE INSIDE

When she first entered prison, Kincaid-Chauncey stayed in a warehouse-type area where 18 women bunked. She later was transferred to a cubicle for two prisoners which had a writing table. She earned the nickname Mail Call Mary, because each time mail arrived, she received about 50 letters. Most were from members of her church.

She passed the time by taking classes: computer courses, yoga, crochet, health, sign language, Spanish, even one in vehicle maintenance.

"I can change the oil, although I don't intend to," she said, laughing and motioning toward her husband. "I'm going to watch and make sure he does it right."

She won an award for walking 1,000 miles during her incarceration. She tried to stay healthy, knowing medical treatment is not the best in prison. Meals consisted of hamburger Wednesdays and chicken Thursdays and pasta in between. She won't mind if she never eats a jalapeño pepper again; it was a main ingredient in every meal because of the camp's large Hispanic population.

She started out cleaning toilets before she moved to kitchen duty.

"The weirdest part is everyone was expecting me. They'd say, 'Were you the one who was a politician?' There are no secrets in that place. Maybe that's why they had me cleaning toilets, to show that I wasn't above anyone else."

She wasn't exactly prison material, but Kincaid-Chauncey picked up the lingo; she still talks about being "on the outside." Harassed by one inmate, for example, Kincaid-Chauncey said she finally "lost it," telling her to mind her own business.

It probably wasn't the worst the woman had heard, but Kincaid-Chauncey soon regretted her response:

"I felt so awful. I felt so bad I went to her room and apologized."

She made friends, one of whom is serving 10 years for her leadership role in an anti-tax movement. Lynne Meredith is considered one of the more high-profile tax protesters, but Kincaid-Chauncey said the woman is brilliant and was a good friend.

Eventually, Kincaid-Chauncey became a mentor to other inmates, comforting and counseling new arrivals.

She recalled how her own mentor was a bit abrasive when she first was incarcerated. When staff asked her to take over the job, she agreed, feeling she could provide a more positive experience for people coming into the system.

During the day, she was free to move about the prison, interacting with inmates in classes or on work detail. But at 10 p.m., the rule was lights out and everyone had to be in their cubicle. She usually was in bed at least an hour earlier.

Though she said detention staff treated her well, she had one depressing experience. Her older brother died in a house fire in Oklahoma, and the warden refused her request for a furlough so she could go to his services.

Still, the December day Kincaid-Chauncey left the camp to transfer to the Las Vegas halfway house, she shed tears. She is prohibited from contacting her fellow inmates until everyone is released and serves their probationary period.

"It's awful. You live with these people, eat with these people and work with them," she said. "Then when you leave, you're supposed to be completely detached."

NO HARD FEELINGS

She has been detached from her former colleagues on the commission, but harbors no ill will toward them.

She met inmates who had been housed in a Phoenix prison camp with Erin Kenny, a former commissioner who pleaded guilty to accepting bribes and who assisted the government with its prosecution of Kincaid-Chauncey.

She has heard Kenny is teaching classes and that inmates have found her to be friendly. Kincaid-Chauncey said she understands Kenny was doing what she had to when she took the stand and offered testimony that helped land her in prison.

"She had to do what she thought was best for her family," she said of Kenny, who is scheduled to be released in December. "I suffered for it, but obviously I'm not as important to her as her family. I felt sorry for her (on the stand). I wanted to tell her 'It's going to be OK.' She looked horrible."

Kincaid-Chauncey said local residents, many of whom lived in her district during her 15 years as a North Las Vegas City Council member and eight as a county commissioner, have been supportive since her release. As of today, she no longer has to check in with her probation officer.

Kincaid-Chauncey wants to proceed with the appeals process. All her children have careers, and she doesn't want her past to haunt them.

"Ninety percent of the people will still think I'm a crook even if they turn it (the conviction) over. But I don't want someone to say they (her children) can't be promoted because the apple doesn't fall far from the tree."

Kincaid-Chauncey offered a few examples of where she believes the jury went wrong. Jurors questioned why wiretaps captured her thanking Galardi over the phone following a lunch with Lance Malone, Galardi's lobbyist who pleaded guilty to paying off commissioners.

Kincaid-Chauncey said she thanked Galardi for donating money to Opportunity Village during a time she was trying to raise money for the nonprofit organization.

She scoffed at prosecutors' argument that when Malone called the flower shop and ordered 10 dozen roses, it meant he was going to give her $10,000.

"Everyone called the flower shop and said things like that; it was a joke," said Kincaid-Chauncey, who took the stand in her own defense.

"They say you are innocent until proven guilty," she said. "That's not true. You have to prove your innocence. How do you do that? There is no physical evidence that you didn't do it."

Until the trial, when Kenny detailed payments she received from Galardi and a development company, Kincaid-Chauncey said she never believed any commissioners were on the take. When someone would suggest one of her colleagues was taking a bribe, she dismissed it.

"Little did I know," she said. "I think I was pretty stupid; too naive to be in politics. In retrospect, I guess I was. I just trust people. I like to think the best of everybody."

SURVIVING

Although prison was surreal at times and a culture shock, Kincaid-Chauncey survived the experience by knowing who she is inside. She refused to be humiliated. Now she is a humbled former public servant who happens to have a lively sense of humor.

Her husband visited her every Sunday.

"I think this whole thing was harder on him and the kids than it was on me."

At home, on Friday, Bob Chauncey handed her an election flier for Stephanie Smith, a one-time political foe who now is running for North Las Vegas mayor. Kincaid-Chauncey chuckled as she tossed the mailer onto the counter.

"I guess she's lucky I can't vote."

Bob Chauncey turned to the living room where their grandson was watching "SpongeBob Square Pants." The episode included a prison scene.

"Look, honey, your show is on. They're making license plates and breaking rocks," he said, clearly proud of his joke.

"Very funny," she replied, cracking a smile.

Contact reporter Adrienne Packer at apacker @reviewjournal.com or 702-384-8710.

Slideshow