Military honor recipient celebrates 90th birthday

Like many young men of his generation, Jack Mates didn’t talk much about what he did or experienced in the military during World War II. He came home, got married, raised a family and pursued a career that would adequately support him, his wife and kids. Reliving war exploits just didn’t’ seem that important to him.

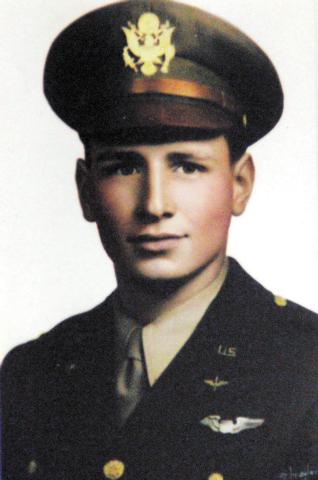

Today, Mates is retired and living comfortably in Southern Nevada where he recently celebrated his 90th birthday with family and friends. The only hint of a military career is a small framed exhibit of six medals affixed on a blue background circling a wallet-sized photo of him as a young soldier in dress uniform. But it’s the medal at the base of this exhibit that, to anyone familiar with its hallowed history, speaks volumes of the humble man who earned it when his country called and he answered without question.

The medal, a Distinguished Flying Cross, is awarded for “heroism or extraordinary achievement while participating in an aerial fight.” Mates, chairman emeritus of the Distinguished Flying Cross Society, says it’s the only military honor awarded by peers or an immediate superior and therefore carries a lot of weight on a personal level.

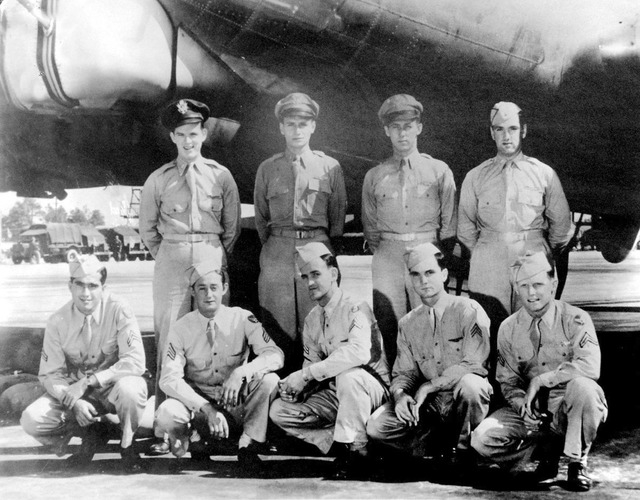

Mates piloted a B-17 Flying Fortress in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations during World War II; many of his missions were scheduled to drop bombs over Germany targeting airfields, gasoline facilities and factories. Enemy aircraft in the air and on the ground were frequently encountered. Mates was stationed with the 15th Air Force, operating at the time out of a base west of Naples, Italy.

“The flak is hitting all around you while the bombardier controls the plane toward the target,” Mates said of the deadly dance he and his crew faced on routine bombing runs. “Everybody flies in tight formation, 28,000 to 34,000 feet. … You have to keep going no matter how much flak is around you. Sometimes when we came home the plane looked like Swiss cheese from being hit so much, but the B-17 was made to take it”

Luckily, no one in Mates’ crew was killed out of all the missions they flew, but some were hit by bullets or flak.

“The flak was so thick we used to kid about going out and walking on it,” Mates said with a smile. “We always just hoped that if we got hit a fire wouldn’t start on board, or someone didn’t get killed.”

Mates enlisted at age 19 in November 1942 as a cadet with the Army Air Corps, predecessor of today’s Air Force. He was sent to Nashville, Tenn., for 13 months where he underwent extensive testing and was told he qualified to become a pilot. In March 1944 Mates received his wings to fly multiengine planes.

At Lockbourne Air Force Base near Columbus, Ohio, the novice flier received advanced training on US-78 aircraft, affectionately dubbed the “Bamboo Bomber” because of its wooden construction. After this Mates was certified to fly “Heavies,” which at the time included B-17s and B-24s.

Mates says he was credited with flying 61 missions, most of which were over Germany. Every time he flew over the Alps, he was given two mission credits for the journey.

“The Tuskegee Airmen were some of the first fighter pilots to protect us,” Mates says. “They were based out of Italy and escorted us on bombings.”

The only close call Mates remembers, where he thought he might have to ditch the plane and parachute out, was when he lost two engines on his way home to Italy. The gauges read extremely low fuel levels, so the crew immediately started dumping gear out of the plane to make it lighter. Surprisingly, in spite of what the gauges read, they were able to land safely — with only about three gallons of fuel left.

“That was the first time … I thought we weren’t going to make it,” Mates said. “The second time was when we were flying over Gulf Port, Miss., when we hit a storm near New Orleans. I was afraid we were going to flip. The B-17 wasn’t made to fly once you get over 45 degrees.”

But luckily, Mates was able to straighten the plane out and land safely, surviving another storm in his illustrious military career.

Mates was still stationed in Naples when World War II ended. Soon afterward, he was sent back to Lockbourne and reassigned, of all things, to the motor pool. He never flew planes again after his discharge in November 1948.

Mates went on to pursue a marketing career in a unique new product called Velcro, which was becoming commercially successful in the 1950s. He would eventually become the president and CEO of Velcro USA, one of several divisions of Velcro Corp. that included several international divisions.

The Distinguished Flying Cross Society was conceived by Alexander Ciurczak, a retired Air Force captain who was twice awarded the cross. He, along with Mates, Bill Coats and Wayne Turner set the wheels in motion to form the society and, on the 50th anniversary of D-Day (June 6, 1944), the Distinguished Flying Cross Society became an official nonprofit organization.

The goals of the society are to keep in touch with its 6,000 members and to promote education about the war, especially with younger generations.

“We want younger generations to know going to war was a job that had to be done,” Mates says. “We never discussed it when we came home. … It was an experience that money couldn’t buy. It was a great opportunity for fellows from different parts of the nation to get together and to understand that there are other things going on in the world. It made a hell of a difference in my life.”