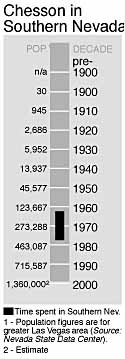

Ray Chesson

One morning in 1965, my mother was sipping a cup of coffee at the kitchen table, when she suddenly turned purple, lurched forward as if taken by a seizure, and spewed coffee violently from both nostrils. The seizure became a laughing fit that continued for minutes.

I later retrieved the soggy sheet, the Nevadan, the Review-Journal's Sunday magazine, and read the story myself. I never again started my Sunday paper with the comics and, at age 12, I first became aware of the power of the printed word. Like scores of other young Southern Nevadans, I thus cut my literary teeth on the tales of Ray Chesson.

Dr. John Irsfeld, a UNLV English professor, later recalled, "It didn't take me long to conclude, after I arrived in Las Vegas in 1969, that Ray Chesson was the best writer around." He went on to admit that on one occasion, he "lifted" Chesson's favorite character, Badwater Bill, and put him in one of his own novels. It didn't work.

"The truth is, I couldn't make him do what Ray Chesson could make him do," said Irsfeld.

Chesson's genius was his clarity. Each word of his prose was carefully considered, agonized over. The images and personalities that emerged were as clear as the Mojave by moonlight, as pungent as smoke from a mesquite fire. His characters, though wildly eccentric, were absolutely real and absolutely hilarious.

Chesson was able to convey a sense of place and time. It was of a place not yet civilized, but moving toward it at a good clip. Every other local writer of the time was obsessed with Southern Nevada's march to the future. Not Chesson. His settings were the East Mojave and Colorado River country, which were straggling out of the past.

His people were on the fringes of society: drunks, wastrels, the homeless. Chesson saw them simply as free spirits, like himself.

He was similarly ahead of his time in writing and illustrating a series of articles on the wildlife of the Mojave and Great Basin deserts. This was a groundbreaking project. Nearly all Southern Nevada residents were from somewhere else, and Chesson's series introduced them to their new furred and feathered neighbors, and did so in the broad forum of a general circulation newspaper. With his friend and editor Bill Vincent, Chesson fostered respect for the desert environment.

"Once, I tried to get him to come into the office and work for the Nevadan," recalled former Review-Journal Editor Don Digilio in 1990. "He said he'd die if he had to work in the office and especially if he had to wear a necktie."

Mostly, Chesson worked in saloons. When small tape recorders were introduced, he tried using one on his normally garrulous subjects. They became quiet and wooden, so he tossed it. He even eschewed conventional note-taking, perfecting his own method. As he listened to a story, he would keep a hand in his pants pocket, scribbling notes onto a folded sheet of paper with a stub pencil. Every so often, he would pick up his beer can and go to the restroom, translate his scratchings into longhand, and dump out about half his beer so as to maintain sobriety -- and appearances.

Chesson was born in 1907 in Moyock, N.C., and studied art for about a year, then went to work as a freelance pen-and-ink illustrator. After overhearing a couple of fellow artists boasting that they could write as well as any magazine scribe, Chesson bought a typewriter and tried his hand. His words and art appeared in Colliers, Field & Stream and numerous other magazines, mostly the outdoor kind.

Despondent over a divorce, Chesson saw "Funeral Mountains" on a map in the 1940s and set out for Death Valley to die. But his health and spirits improved and, in 1954, he met and married Peggy Chesson, with whom he would spend the remaining 36 years of his life. Chesson died in 1990 at the age of 83, and his last Review-Journal byline had been 13 years before that. Yet to this day, the Review-Journal occasionally gets phone calls asking for one more story by Ray Chesson.

Here is one of those stories -- Chesson's own account of his years celebrating characters and a lifestyle already vanishing as he wrote.

Part III: A City In Full

RELATED STORY

My friends, oft pursued and sorely beset, by Ray Chesson