SNWA thins palms, upsets Warm Springs residents

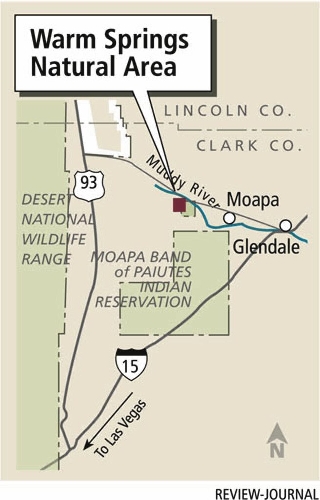

MOAPA -- In a green pocket of northern Clark County where the Muddy River springs to life, some residents wonder where their oasis went.

Tensions are running high in the Warm Springs area 60 miles north of Las Vegas, where the Southern Nevada Water Authority bought up land to protect a rare fish but has endangered relations with the locals in the process.

Lately, it's the sound of chain saws that has residents buzzing.

Over the past year, workers have cut down some 900 wild palm trees on the fenced, 1,200-acre tract the authority bought in 2007 and now operates as the Warm Springs Natural Area.

The removal of the valley's signature tree has angered some adjacent property owners and spawned an unlikely activist.

Shaine Williams is a junior-to-be at Moapa Valley High School. Early this year, the 15-year-old drew up a petition aimed at saving the palms that line the valley she calls home. Then she recruited her grandmother to drive her from house to house so she could rally people to her cause.

"Everyone kept saying someone needs to do something. I just got tired of sitting back and nothing happening," Williams says.

In a week and a half, she collected more than 350 signatures from residents as far away as Overton, 25 miles downstream from the Warm Springs area.

In the comment section of the petition, one person wrote: "They are turning an oasis into a wasteland."

Another person wrote: "Stop managing our beauty to death."

FOR THE FISH

Before the Southern Nevada Water Authority took a lead role in protecting the endangered Moapa dace, the regional agency was widely considered one of the biggest threats to its survival.

For decades, the authority has pushed a plan to tap billions of gallons of groundwater across rural Nevada. One of the links in that pipeline network is Coyote Springs Valley, just west of the palm-lined springs and streams at the upper end of the Moapa Valley.

Authority officials became chief defenders of the finger-length fish under a 2006 federal agreement that also cleared them to pump water at Coyote Springs.

The following year, the authority paid nearly $69 million for 1,218 acres of ranch and retirement property Howard Hughes once owned in the Warm Springs area.

One of the first things the agency did was fence off the land to reduce potential liability and keep out vandals, off-road vehicles and other possible threats to the watershed.

Virtually the entire natural habitat for the Moapa dace now rests inside the authority's fences and in the adjacent, 117-acre Moapa Valley National Wildlife Refuge. The fish is found nowhere else in the world.

"This is one of the most ecologically significant properties in Southern Nevada," says Bronson Mack, spokesman for the water authority. "We need to make sure any groundwater pumping in that area does not impact the dace habitat or the Muddy River."

Mack says the authority is done chopping down palm trees, at least on a large-scale basis.

The roughly 900 trees removed over the past year represent about one-third of all the palms on the authority's land. It was never their intent to wipe out all of the trees, he says.

In some places palms were removed to improve fish habitat. In others, thick groves were clear-cut to create fire breaks and prevent a repeat of a July 1 blaze that swept onto neighboring properties. A work crew hired by the authority accidentally sparked that fire while clearing brush to cut the risk of wildfires.

Several homes and other structures burned, including large portions of the Warm Springs Ranch, a private, 72-acre recreational area for members of the Mormon church.

Damage was estimated at $2.5 million.

LACK OF TRUST

Birds sing and water gurgles through a stand of palm trees at the southern edge of Tim and Lori Wood's property.

They have built themselves a small, white-sand beach along the shaded stream, where several different kinds of tiny fish dart in the current. A few of them might be dace.

The Woods' 7-acre slice of paradise is now bracketed by blackened tree stumps and bare earth marking the disputed property line they share with the water authority.

Since the fire, which burned through their property and took out some vehicles, the couple have lost whatever trust they had in their powerful neighbor from Las Vegas.

Lori Wood doesn't even believe water authority officials when they say they care about the dace.

"It's not about the fish. That's just an excuse to gain control of a large area and make a ton of money in the process," she says. "It's about the water. You control the water, you control everything."

As far as Bill Parson is concerned, the palm trees are part of a larger problem in his neighborhood: government run amok.

Parson and his wife, Linda, settled at the headwaters of the Muddy River in 1998. Last year, he was an also-ran in the Republican primary for Harry Reid's U.S. Senate seat, in which he campaigned as a strict constitutional conservative.

The retired Marine objects to the authority's attitude, its fences and the way it is managing the land just south of his property.

For all the talk of protecting the dace, he says, "the species we never hear any concern for out here are the homo sapiens."

Parson also has a specific beef with the authority, which asked to use his private drive and then drove trucks on it anyway after he said no.

Since then, he says he has come home from work to find surveyors from the authority trespassing on his property without his permission.

Then there was the fire, which destroyed the Parsons' barn and more than $100,000 worth of equipment inside.

Parson says he has no faith in the authority's plan to prevent another blaze because he sees no evidence of a plan -- for that, or anything else they are doing.

Just look at the job they and their federal partners have done with the dace, he says. The fish has never been closer to extinction.

MOAPA MATH PROBLEM

Parson has math on his side if nothing else.

The Moapa dace has been under federal protection for more than 40 years, but results so far have been mixed.

In 1994, for example, the Warm Springs area was home to some 3,825 dace. Then a fire in the palm groves that summer dropped smoldering fronds into the water and wiped out about half the population.

The species was also pushed to the brink by an invasion of tilapia, a non-native game fish that found its way up the Muddy River in the 1990s to feed on both the dace and their food.

But one of the largest and most alarming declines occurred sometime in 2007, when the numbers plummeted from 1,172 to 459.

Experts still don't know why.

Initially, federal officials said habitat restoration activities might be to blame, but the population fell almost everywhere dace are found, not just in the streams where the work was being done.

Current Moapa Valley National Wildlife Refuge Manager Amy LaVoie says the die-off could have been caused by a combination of factors or it could have occurred naturally as part of what she called a normal "life-history event for the dace."

"Nothing has precisely been pinpointed on that," she says.

Since 2007, the population has hovered between 500 and 700, suggesting that whatever was happening to the fish isn't happening anymore.

Despite the uncertainty, officials insist they are making progress.

Mack says the upper reaches of the Muddy River were recently declared tilapia free for the first time since the mid-1990s.

Recent counts, meanwhile, show Moapa dace concentrating in areas where streams have been restored to their natural state.

"I just believe we are creating a more healthy environment for the dace and other aquatic species out there," LaVoie says.

Thinning the palm trees also appears to be working, Fish and Wildlife Service spokesman Dan Balduini says.

Last year's fire started directly across the street from the refuge, but its trimmed and well-spaced palms were largely untouched.

"What burned? Unmanaged palm trees. They just went up like newspapers," he says.

The last official count in February pegged the Moapa dace population at 574. The next count will take place in August.

The fish is expected to remain under federal protection until at least 75 percent of its historical habitat has been restored and its population is holding steady with at least 6,000 adult fish.

It is unknown when, if ever, those benchmarks might be reached.

MORE OPENNESS

Both Mack and LaVoie say there are area residents who support what their agencies are doing.

But Mack isn't surprised by the reactions of those who don't, particularly when it comes to the palm trees.

"The Warm Springs holds so many good memories for them," he says. "I absolutely understand where they are coming from. It's about maintaining the aesthetic of the place."

Officials believe some of the distrust and anger from neighbors will fade with time. Granting some public access to the land should help, too.

The Southern Nevada Water Authority just issued the final draft of its Warm Springs Natural Area Stewardship Plan, an 80-page document that details the agency's current and future work. Mack says "controlled public access" to the property is "absolutely" part of that plan.

By next year, the authority hopes to finish a short hiking trail and some interpretive signs around one of the springs. Eventually, more of the fenced property will be opened up to picnickers and bird watchers, but activities such as camping, hunting and off-road vehicle use are unlikely ever to fit with the agency's primary conservation mission.

As Mack jokingly puts it: "There will be no dace fishing."

Increased access is also a stated goal for the Moapa Valley National Wildlife Refuge, which has been largely off-limits to the public since its creation in 1979.

As it is now, the small refuge only opens its gates on weekends, except during the summer when it remains closed altogether.

LaVoie says she wants to see the place open "every day and all year long," but it's uncertain when that might happen.

KNOCK ON WOOD

Saving the palm trees was her primary focus, but access is also important to Shaine Williams.

The valley used to have a lot of private property where people could hunt, ride horses and swim with the owner's permission. Much of that has been taken out of circulation by the water authority, which is now the area's single largest land owner.

Williams rides her horse, Opey, around the neighborhood most days, but she says the authority's fences have cut her off from some of the places she used to go.

Once she was done collecting signatures, she presented her petition to the Moapa Town Board and the water authority. The agency responded with a letter explaining its plans and applauding her for her involvement.

Authority officials also offered to show her around the property, an invitation she accepted earlier this month.

Williams says a lot of what she saw and heard on the tour was encouraging, but she, like many of her neighbors, remains skeptical.

"I would just like them to leave it as it is. Leave it natural and open it up, take the fences down," she says. "I'm still not sure they're going to listen."

Contact reporter Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350.