The long road to Interstate 11

NOGALES, Mexico

Mention Interstate 11 around here in the borderland, and you may be met with a blank stare.

It’s for good reason: The highway doesn’t yet exist, at least not as a ribbon of asphalt.

I-11 — meant to eventually link Mexico to Canada, and Phoenix to Las Vegas along the way — now is just a concept. It’s on the drawing board with pieces in various stages of development and urgency, depending on whom you ask.

But it’s the Las Vegas Metro Chamber of Commerce’s top economic development priority. Chamber leaders traveled to Washington in September to make that message clear to Nevada’s congressional delegation. I-11 would ease truck congestion on Interstate 5, where federal projections show nothing but traffic increases and choke points through 2035.

And Las Vegas could potentially siphon off some business that way. Leaders and observers are looking at how local economics could shift if the city starts bringing in more than tourists by the tens of millions.

U.S. Rep. Steven Horsford, D-North Las Vegas, points to estimates that say every dollar spent on interstate funding returns $6 in economic revenue. Horsford is a member of the I-11 Caucus, which includes Nevada and Arizona congressmen.

“Interstate 11 would be a significant return on investment by creating desperately needed jobs to bring down unemployment, particularly in the construction, engineering and architecture sectors that have felt the brunt of the downturn,” Horsford said.

But government types point to transportation studies with no time line for construction. Rural Nevadans say they will be dead by the time the road gets built, and that it might skip their towns altogether. And activists who live in the shadow of the U.S.-Mexican border fence will tell you timing doesn’t matter, then deliver a tongue-lashing about geopolitics.

Such is the life of a future superhighway. It poses complicated questions with uncertain answers, pricey prospects with little money in sight and, sometimes, can open old wounds that time can’t heal.

Las Vegas finds itself at a crossroads, literally and figuratively. With more than 450 miles either direction you drive, Sin City is nearly equidistant from Nogales and Reno, the focus of planning at this point. That’s at the heart of the freeway’s envisioned course, opening up a north-south alternative to I-5 and linking to Interstate 15.

Congress “designated” I-11 as a priority corridor in 2012, but lawmakers didn’t include funding. The chamber particularly wants to speed up the trip between Phoenix and Las Vegas and, way down the road, maybe shave off an hour or more from the nearly full workday it takes to drive to Reno.

But much more is riding on this highway than a speedy ride. For one of the United States’ fastest growing cities of the 20th century to keep moving forward, the Chamber says, it will need more than tourists, gaming and construction. The added boost could be better transportation.

A state-sanctioned report on the potential for making Las Vegas an inland port — where containers of goods go through customs or are switched from one transportation mode to another, say trains to trucks — said the Las Vegas Valley isn’t ready.

Business and government leaders hope Interstate 11 will pave the way for those trucking centers.

“Building one right now just doesn’t make sense,” said Brian McAnallen, the chamber’s vice president of government affairs. “But with I-11, that’s a game changer for Southern Nevada that creates opportunities for inland ports.”

ROUTE TO DIVERSIFICATION

Transforming Las Vegas from an adult playground to a transportation hub is a journey that links the valley to complex issues for our neighbors to the south.

The name Interstate 11 may not be widely known, but it’s a familiar notion for those paying attention to foreign trade policy for the past two decades.

More recognizable is the CANAMEX Corridor, a conglomeration of roads and government agreements drawn together and folded into the North American Free Trade Agreement, in place since 1994. From Mexico this artery runs through Arizona, through Las Vegas and then follows I-15 to Canada.

The new interstate would mostly follow the CANAMEX route from the Mexican border to the Las Vegas metropolitan area. That’s more or less Interstate 19 from Nogales into Tucson, Interstate 10 to Phoenix, U.S. Highway 60 to Wickenburg, Ariz., and then U.S. Highway 93 to Hoover Dam. Past Las Vegas, I-11 would push through Nevada and into either Oregon or Idaho heading toward the Canadian border.

NAFTA was designed to remove restraints from cross-border business. In the broadest sense, it has worked. The latest federal estimates show the value of NAFTA trading has tripled since the agreement started, totaling $1.6 trillion in 2009. In 1993, that number was $297 billion.

Experts expect those numbers to continue growing, with California ports at maximum capacity and increasing international trade coming through new container ports in Mexico.

At the Western Governors’ Association meeting at the Mandarin Oriental in December, regional development guru Michael Gallis repeated his mantra: Cities must adopt NAFTA-style cooperation to diversify their economies and stop acting like individual oases.

Instead, Gallis said, they should be allies. That includes Las Vegas and Phoenix.

The Great Recession proved Southern Nevada can’t depend just on its resorts and local construction to stay afloat. Unemployment in Clark County remains around 8.6 percent, down from a year before but still higher than the national rate which dipped below 7 percent in December.

Linking Las Vegas and Phoenix, the largest adjacent metropolitan areas in the United States lacking a direct interstate connection, would do more than make the drive faster for gamblers traveling from the south, Gallis said. It would build an economic coalition between the cities and help Las Vegas benefit from Mexico’s manufacturing and agricultural capacities.

“It’s an extremely complicated process, and every trading block is competing with every other trading block,” said Gallis, who is based in Charlotte, N.C. “The U.S. would become very noncompetitive without Canada and Mexico.”

‘AMBOS NOGALES’

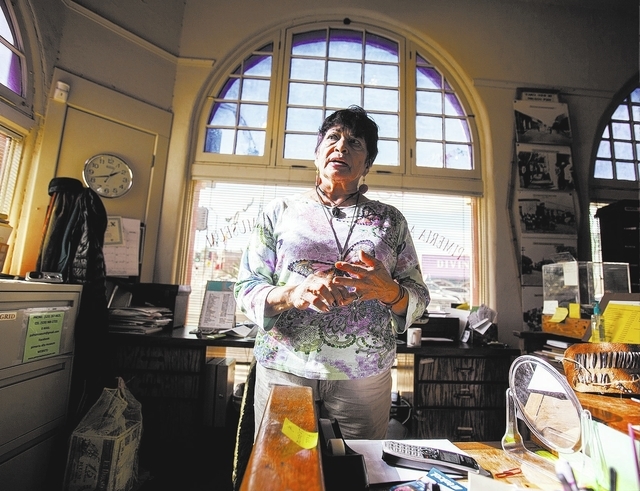

Teresa Leal knows how much the United States and Mexico need each other.

Now in her 60s, she lives in Nogales, in the Mexican state of Sonora, and works in Nogales, Ariz.

Residents on both sides of the border use a collective Spanish name for the two cities: “Ambos Nogales — Both Nogales.”

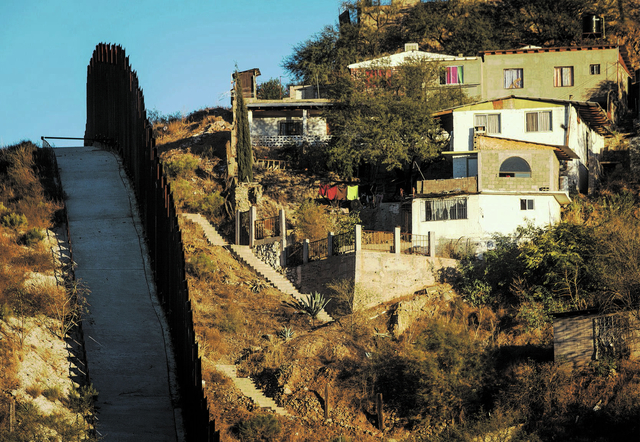

It’s one place, Leal says. There just happens to be 10-foot metal fence running through it. Plus the armed federal agents on patrol.

Signs of Nogales’ duality abound. On the U.S. side, I-19 road signs give distances in kilometers. Window shoppers use Spanish and English interchangeably. On Morley Avenue, shops sell off-brand stereo equipment, mops and diapers. One store posts photos of customers who have bounced checks.

There is a strip mall that would fit just fine in Anytown, U.S.A., where retail choices include rue21 (discount fashion), GameStop (video games and computer software) and Payless ShoeSource (cheap footwear).

On the Mexican side, low-cost dental offices draw Americans for fillings and cleanings. Men offer to wash windows on Arizona-bound vehicles. Barkeeps offer cerveza, and sometimes Viagra.

Getting there on foot is quick and easy; no one asks for documentation. U.S. Customs and Border Protection guards just point to the turnstiles, and you are through in seconds.

Coming back is another story. The lines are long. The border patrol wants identification and answers: Where did you go? How long were you there? What did you do?

On a recent November weekday, getting into Arizona took about 20 minutes.

U.S. Department of Transportation statistics show 3.2 million pedestrians crossed the border at Nogales in 2012, the most recent year for which numbers were available. More than 2.8 million moved through in personal vehicles, as did 246,000 loaded trucks and 64,000 empties. Truck traffic is heavier this time of year, when an estimated 60 percent of winter produce consumed in the United States and Canada comes north.

Leal sees the foot, vehicle and train traffic while working her day job at the Pimeria Alta Historical Society Museum, a block from the downtown border crossing. She raises an eyebrow at the mention of Interstate 11. The self-described activist doesn’t care about a faster drive to Las Vegas, but she is on guard for all things CANAMEX and NAFTA.

She understands economics. For decades Mexican families have shopped on the U.S. side, where stores are less expensive. But when it comes to international policy, treaties and freeways only benefit politicians and corporate executives, not the average person, Leal said.

“It allows these huge corporations to plow right through communities, to do away with the environmental concerns,” Leal said. “Where is the human face to this?”

The estimated 35,000 workers at Nogales’ 90 maquiladoras, factories in Mexico that assemble products largely headed for the United States, are still poor, Leal said. Many of them are addicted to drugs that also travel up NAFTA highways, she said.

Just the day before, U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents in Nogales, Ariz., seized more than 20,000 pounds — $10.1 million worth — of marijuana. It was packed on a truck carrying squash.

Income inequality is a serious but complicated problem, said Gallis, the development expert in North Carolina. But globalization is here to stay. It has changed the way manufacturing and transportation work.

“Nobody makes anything anymore,” Gallis said. “Everybody makes a piece of something, and then it gets assembled somewhere else.”

YEARS IN THE MAKING

By the time rubber meets the road, an interstate has been decades in the making.

There is planning, which is Interstate 11’s current stage, then funding and building. Each of those steps has layers and complexities that can take years to play out.

Even a fast-tracked freeway takes time. Take the Las Vegas Beltway. With explosive population growth in Clark County, the Regional Transportation Commission of Southern Nevada, the Nevada Department of Transportation and business partners have worked since 2003 to link and widen interstates 15, 215 and 515.

The ongoing project is mostly interstate-grade, complete with on- and off-ramps. Stoplights guide traffic at 11 spots, mostly on the northern edge of the Las Vegas Valley. Part of it is still called County Road 215.

Upgrades happening now near McCarran International Airport and between Tenaya Way and Decatur Boulevard up north are scheduled for completion this year.

Once Interstate 11 reaches Las Vegas, it could run the same path as parts of the 215 Beltway. It might feed into I-15 through the Spaghetti Bowl. Or new roads could be built on the western and northern sides of town, all before following U.S. 95 to the northwest.

But regardless of the route, I-11 will take much, much longer to build than the Beltway.

None of the I-11 corridor is called that yet. And that, in part, is because most of it isn’t close to interstate standards.

It may look like the four-lane U.S. Highway 93 between Kingman, Ariz., and Las Vegas is on the verge of interstate designation, but there still is much work in store.

Roads must be leveled, and vehicle access must be limited. That means the government must replace intersections with interchanges. States will have to buy rights of way, often from private property owners who have driveways that connect directly to the highway. That can take years, and often involves lawsuits.

And new freeways have a way of reminding people of what they stand to lose. Small towns in both states are already riled up about a roadway that wouldn’t be traffic-ready for 50 years in some spots, if then.

Folks from Elko, in northeastern Nevada, have been hammering the Nevada Department of Transportation since officials said I-11’s most likely route will be on the west side of the state, largely following the path of U.S. Highway 95. NDOT considered a U.S. 93 route closer to Utah, but chose a straighter path between more populous and busier Las Vegas and Reno.

TUCSON TO PHOENIX

Missing out on a freeway is a threatening prospect. So is getting one.

Some don’t want I-11 anywhere near them.

Residents of Avra Valley, northwest of Tuscon, in October objected to a Pima County plan to loop I-11 around the city to ease traffic on I-10. They fear losing starry nighttime views and gaining increased traffic and sprawl.

Phoenix already has plenty of traffic. America’s sixth-largest city funnels vehicles onto interstates 10 and 17, plus two state highways that loop the metropolitan area. U.S. Highway 60, also known as the Superstition Freeway, parallels I-10 as an east-west corridor toward the suburbs of Mesa and Gilbert.

Arizona and Nevada transportation departments are working on a study that will build a business case for Interstate 11. It’s less about getting produce from Mexico to Canada, and more about building “a more reliable economic future,” said Michael Kies, the Arizona Department of Transportation’s Interstate 11 coordinator.

“We don’t do much manufacturing as a percentage of the economies in Arizona and Nevada. We don’t export products,” Kies said. “But in order for our economies to become more stable from the bust-and-boom cycle from growth and recession, both states see that diversification is required.”

The word interstate generally brings to mind pictures of highways with 18-wheelers and personal cars. But at this point in the game, Kies said, it could mean more. That could be freight or passenger rails that parallel a new road, or a modified version of an existing highway.

LAS VEGAS TO NORTHERN NEVADA

North of Las Vegas, I-11 would fill a missing link between Southern Nevada, Carson City, Reno and Lake Tahoe.

Sure, you can get there from here now, but U.S. 95 northbound drops from four lanes to two about 50 miles north of the 215 Beltway, just past the town of Mercury. From there, it’s a good 350 miles before anything resembling an interstate appears.

Vacationers and joy riders would appreciate passing lanes where they now stall behind lines of tractor-trailers snaking past Walker Lake. But the real reason for building a freeway is to make more room for trucks.

At first blush, that is good news for Reno-area trucking companies and their advocates. And to the dismay of Southern Nevadans who thumb their noses at the Biggest Little City in the World, Las Vegas could take a cue from the way Reno’s transportation industry has developed.

Like others, Jeff Lynch, CEO of Sparks-based its Logistics, would like to know a few more details about how much the freeway would cost, who will pay for it and exactly where it will go. But the potential of a faster route to Las Vegas and Phoenix has appeal.

“We minimize our presence down there now because of the inefficient system in and around Phoenix, and getting to Phoenix,” Lynch said.

That means slow-going on two-lane Highway 95 to Las Vegas, and stop-and-go traffic at Boulder City, where a bypass is still three or four years off.

Most of Lynch’s trucks run on one-day turn-arounds of 500 to 550 miles into California, or shorter in-state runs. The company hauls everything from the As Seen on TV AB Circle Pro Machine to Seagrams Seltzer Sparkling Water and Starbucks coffee beans, which are roasted in Minden, south of Carson City.

Paul Enos, CEO of the Reno-based Nevada Trucking Association, said his Southern Nevada members want the Boulder City bypass. Cost-benefit ratios must work out right before his organization backs any project, Enos says, but he generally takes a universalist approach, pushing a united Northern Nevada and Southern Nevada.

“There’s not one place in the state of Nevada where it could sustain itself without products from somewhere else,” said Enos, himself an Elko native.

Members of his association move everything from “cold medicine to cantaloupes,” he said.

Another potential benefactor of I-11 is the Tahoe Reno Industrial Center, nine miles east of Reno in Storey County. The 107,000-acre industrial park is home to distribution centers for Wal-Mart, eBay and Toys R Us. Most products come and go via truck — nearly 2,500 a day by the park’s 2012 count.

Storey County has streamlined ordinances for the center, called TRIC locally and marketed as the world’s largest industrial park. Permits for plants that would process fuel, make food or manufacture paint, among other activities, can be approved in a month’s time. That process can take six months or more in other locales.

The industrial park’s director is Lance Gilman, who also is a Storey County commissioner and current owner of the Mustang Ranch brothel. Gilman said his goal from the get-go was to make this place known internationally. That’s why he picked the name.

“More people knew where Lake Tahoe was than Reno,” Gilman said. “They thought Reno was a bedroom community for Las Vegas.”

Gilman also is in the business of pushing the state transportation department for new roads. But his pet project is finishing USA Parkway, to connect the industrial park with U.S. 50. It already links to I-80.

State officials tell him they don’t have the $50 million needed for 12 miles of the route. There is not as much highway-building money anywhere these days.

I-11’s FIRST LEG

Nevada and Arizona officials won’t put an official price tag on the roughly 300 miles of I-11 that would link Las Vegas and Phoenix. Figures from $5 billion to $10 billion get floated.

Just for perspective, building nearly 43,000 miles of the Interstate Highway System cost an estimated $129 billion, with 90 percent federal funding, since 1956, according to the Federal Highway Administration. That revenue came from the Highway Trust Fund, culled mostly from federal fuel tax revenue.

About 4,000 more miles were built with other funding mechanisms, some of which likely will be used for I-11.

The Congressional Budget Office predicts the Highway Trust Fund won’t be able to meet its obligations by 2015. Since 2008, federal lawmakers have moved $41 billion from the general fund to avoid shortfalls. Because of inflation and increasing fuel efficiency, a federal requirement for new cars, the fund doesn’t stretch as far.

Congress could raise taxes by a dime per gallon of gasoline or diesel to boost revenue, the budget office projects.

But there’s a fat chance of that happening, as Tom Lewis, a professor at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., points out.

“As we all know in the United States, which was founded in part on tax revolt, ‘tax’ is a four-letter word in our vocabulary,” said Lewis, author of “Divided Highways,” a history of the interstate system.

The Clark County Commission embraced that four-letter word in September in a move to finance the first piece of I-11. In a 6-1 vote, commissioners approved an increase in the local gas tax that will add up to 10 cents to the cost of each gallon of fuel purchased during the next three years, depending on inflation.

The initial increase, 3.24 cents, went into effect Jan. 1. More will hit every July between 2014 and 2016.

Part of the revenue will pay for the initial stretch of I-11, the 17-mile Boulder City bypass. The entire loop is expected to be done by 2018 at a cost of $90 million to $100 million, and it will ease traffic around the gateway to Hoover Dam.

But before Nevada can claim first place in the race to build I-11, it must smooth other over some legal issues that could cost as much as the construction.

The state expects to pay about $60 million for land needed to build the bypass. Railroad Pass Casino property could cost $14 million, and K&L Dirt, which would have to move for the highway to come through, could run another $12 million.

And then there’s a 3-acre triangle that is part of an 82-acre property zoned for apartments or condominiums, on the southeastern edge of Henderson. The Henderson Planning Commission approved the Jericho Heights housing project in 2008, pending state approval of access to Boulder Highway. Since then, developer Randy Schams and state transportation department officials haven’t been able to agree on an access point or a price for the freeway right-of-way. The two sides remain far apart. At one point, the state was willing to pay $337,000 and Schams wanted $33 million.

A jury trial is set for July.

THE ANTI-VEGAS

What Boulder City and all towns along the way must consider is that the highway may give, but it also could take away.

Just 30 minutes from the Strip — barring a car crash or a 20-minute backup before traffic splits toward downtown or continues east toward Hoover Dam — it is the anti-Sin City.

That’s by design.

The federal government built Boulder City for Hoover Dam construction workers, starting in 1931. Congress privatized the town in 1958. Since then, voters have adopted growth controls that limit the number of houses that can be built. The population has stayed around 15,000 since 2000, even as Las Vegas grew fast.

Most businesses are family owned, and there is no Wal-Mart or gambling.

It’s the perfect place for a getaway for Henderson couple Ross and Kim Herman. Boulder City is close enough that they can get back to their kids quickly if need be, but it also feels a world away.

Both grew up in the Chicago area, where they said neighborhood character gave the place a more intimate feel. The Las Vegas Valley’s cinder block walls and stucco subdivisions make that harder, but Boulder City offers just what they are looking for. The Hermans don’t want that to change.

The couple spent a recent Friday night — their fourth in a year — at Milo’s Inn at Boulder. For much of that evening, they sat in the bed and breakfast’s courtyard, near a gas-powered fire pit adjacent to a pond with bright orange koi. They sipped sangria and caught up on a little reading via an iPad or novel.

With a new freeway coming through, the Hermans don’t want the commercial detritus that accumulates at interstate exits — fast food and truck stops. Or, as they put it, “a new Primm.”

“Here, they’ve got their own niche, and it’s just so nice to have that homeyness,” said Ross Herman, 39. “There’s no casinos, so you don’t hear the dings and see the blinking lights.”

Milo Hurst, owner of the Inn at Boulder and Milo’s Cellar wine bar, also wonders what the future holds. He expects more tourists with faster access via a traffic-easing freeway, especially if Boulder City markets itself as a destination, not just a stopover on the route to Hoover Dam or Phoenix.

But he also doesn’t want that to drive up downtown rents so locals — accountants, antique dealers, restaurateurs — must give up what makes the town nice, like being able to walk down the sidewalk to get a haircut.

“We may have to reinvent ourselves a little bit,” Hurst said. “We’ll have to strike a balance.”

As Tom Lewis, the “Divided Highway” author says, good and bad consequences also lie in the balance. Freeways create sprawl. Businesses pop up at on- and off-ramps.

“It can provide an enormous economic boost. At the same time it will come at a price to the environment and the society.”

FARTHER DOWN THE ROAD

Folks in places such as Goldfield, Tonopah and Hawthorne — all on Nevada’s U.S. 95 corridor — know how to face the cold, hard facts of progress and change. Those towns are icons of Nevada’s 20th Century economic model: the boom and bust.

The Hawthorne Army Depot helps keep its namesake in Mineral County alive.

Goldfield’s peak, much like Tonopah 25 miles north, came during the gold rush that started in 1900. With 30,000 residents in 1906, Goldfield was the state’s biggest city. Now the two towns have a combined population of less than 3,000.

Tonopah’s economy recently has seen an uptick with the building of the 110-megawatt Crescent Dunes Solar Energy plant, with an estimated 600 construction jobs. SolarReserve, the plant owner, will sell enough electricity to NV Energy to power 75,000 homes at peak capacity.

But construction jobs are temporary, and both remote towns rely on revenue from tourists, many of whom stop on their way to and from Las Vegas to Reno or Carson City.

Eight members of the Rotary Club of Tonopah who gathered for a December lunch meeting at Kozy Korner agreed that it would be better for I-11 to come close, but not plow through the center of town in U.S. 95’s footprint.

That’s not an issue for Goldfield, where U.S. 95 makes a hard 90-degree turn near the center of town. Any freeway would have to bypass the near-ghost town. And for now, transportation experts are looking at swaths 50 miles wide while considering routes.

The Tonopah Rotarians’ hopeful opining came with understandably skeptical quips of people who have seen ideas blossom and die. Many don’t expect to be on the planet for I-11’s completion.

“By the time they get a freeway built, we’ll be flying cars,” said Ron Browning, a Bay Area transplant who runs Safetee Connections, which prints vinyl signs and sells safety gear.

That day, other business was more urgent: A club member was being treated for cancer at a Sparks hospital and needed financial help. The annual club fundraiser is coming up. The Cline family, which reopened the five-story Mizpah Hotel in 2011, will open a microbrewery this year.

But the planning phase is the best time to speak up, advises Sondra Rosenberg, Nevada Department of Transportation I-11 coordinator, whose office is in Carson City.

“It’s time for them to do their plan for their community and figure out where some enhanced highway fits into that,” Rosenberg said.

THE UNKNOWN

Small towns aren’t alone in facing an uncertain future.

Steady revenue can be daunting for a state like Nevada, where the unpredictable industries of gaming, mining and construction have ruled.

Since Congress eliminated earmarks, the Nevada transportation department is considering other ways to pay for highways.

Interstate 11 likely would connect military bases throughout Nevada, Rosenberg said, so there could be partnerships with the U.S. departments of Defense or Homeland Security.

But bringing tolls into the discussion makes drivers, lawmakers and bureaucrats squirm.

“Right now we don’t have a silver bullet,” Rosenberg said. “We don’t have an answer.”

Meanwhile, other road enhancements are higher on the transportation department’s priority list. One is Project Neon, the 20-year and nearly $2 billion widening of Interstate 15 from Sahara Avenue to the Spaghetti Bowl.

But Nevada is built on unknowns and chances taken.

According to the 1960 Census, just four years after construction of the interstates started, slightly more than 285,000 people lived in the whole state. Fast-forward 50 years, and interstates 80 and 15 cut through, and the population has increased nearly tenfold, to 2.7 million. Then, Reno was the population center. Now, most live in Clark County.

There wasn’t much of a Strip in 1960, and now it is lined with high-rise hotels and gaudy casinos that draw 40 million visitors a year to the middle of the Mojave Desert.

As Las Vegas considers its place on a new path, the future is still a wide open road.

Contact reporter Adam Kealoha Causey at acausey@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0361. Follow on Twitter @akcausey.

Additional maps:

Alternate routes through Nevada considered for Interstate 11

Routes through the Las Vegas Valley

Routes considered through Phoenix and western Arizona

Ports and sources of freight served by Interstate 11 project