EDITORIAL: U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas raises questions about civil forfeiture

On Monday, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal in Leonard v. Texas. Nothing unusual in that. The high court takes up only about 100 cases each year out of more than 7,000 requests.

But as UCLA law professor Eugene Volokh noted in his blog this week, despite refusing the Texas case on technical grounds, one justice hinted that the law enforcement tactic known as civil asset forfeiture may be on borrowed time.

Leonard v. Texas involved an April 1, 2013, traffic stop of James Leonard. A search turned up a safe in the vehicle’s trunk and when Mr. Leonard and his passenger gave conflicting stories about what was inside, the police quickly secured a search warrant.

The safe contained $201,100 and the bill of sale for a Pennsylvania home.

Mr. Leonard was not charged with any crime. But prosecutors initiated forfeiture proceedings on the assumption that the money was tied to the sale of illegal drugs. Mr. Leonard’s mother claimed the money as hers and said she earned the cash through the sale of a home.

The Texas courts rejected her claim.

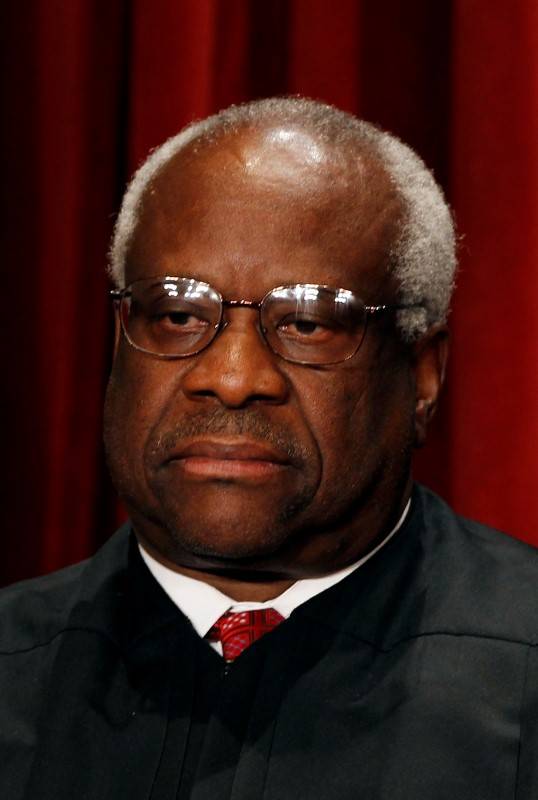

While Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas agreed that the high court must turn down Ms. Leonard’s appeal for procedural reasons, he made clear in a written opinion that he harbored concerns about the constitutionality of such police actions.

Justice Thomas noted that under civil forfeiture laws — which have proliferated since the 1980s and allow police to seize valuables on the mere suspicion of illegal activity — prosecutors essentially charge the property itself with wrongdoing. This allows the matter to be decided in civil court where “proceedings often lack certain protections that accompany criminal proceedings, such as a right to a jury trial and a heightened standard of proof.”

Justice Thomas goes on to question the cozy arrangements that allow police agencies to keep a portion — if not all — of the money raised by the sale of forfeited assets, citing “egregious and well-chronicled abuses.” He also points out that “forfeiture operations frequently target the poor and other groups least able to defend their interests.”

Justice Thomas acknowledges that the high court over the years has sanctioned the practice because it existed at the time of the nation’s founding as a way to combat piracy and customs violations. But “I am skeptical,” he wrote, “that this historical practice is capable of sustaining, as a constitutional matter, the contours of modern practice … .”

This is welcome news to those who have long complained that civil forfeiture is an affront to both due process and property rights. Justice “Thomas is sending a signal, I think, that at least one justice — and maybe more — will be sympathetic to such arguments in future cases,” Mr. Volokh concludes.

This is just one more reason why states — including Nevada — should reform their statutes to require a criminal conviction before property may be forfeited. No one should lose his home, cash, car or other valuables based on the whim of law enforcement officials.

In the meantime, let’s hope another case challenging the constitutionality of this controversial practice quickly makes its way to the U.S. Supreme Court.