Combine-Ready: Preparing for NFL draft requires players to push bodies, minds

SAN RAMON, Calif. — Colby Parkinson used the vast majority of his hour of solitude floating in 10 inches of body-temperature salt water getting connected to his spirituality.

Inside the sensory deprivation tank, he allowed his mind to wander a bit to the monumental task ahead of him.

“I definitely did some visualization of running a fast time in the (40-yard dash) and getting that positive feeling going,” he conceded.

It’s no surprise that particular event creeped into his mind. Parkinson is a tight end who will attend the NFL Scouting Combine in Indianapolis this week after forgoing his senior season at Stanford to declare for the draft. The ‘40,’ a number tossed around more than even a football this time of year in these circles, is the premier drill at the annual combine, the so-called “Underwear Olympics” where prospects are poked, prodded and probed by NFL scouts, coaches and executives.

Related: Raiders’ Johnathan Abram talks about NFL Combine experience

His time in the float tank is part of an immersive preparation experience designed to make sure his body and mind are as ready as possible for what is essentially a weeklong job interview.

Parkinson is one of seven players training for the combine at California Strength, a gym 20 minutes east of Oakland that is one of several facilities that has emerged in a booming industry that prepares football players for the draft process.

The concept

Dave Spitz was a noted weightlifting trainer who had worked with many athletes from middle school through world-class level when he was approached with an unusual proposition in 2010.

Defensive back T.J. Ward, whom Spitz had trained for years, asked for help preparing him for the scouting combine after a successful career at Oregon. Spitz initially declined, insisting he didn’t even know what that would entail.

“T.J. just said, ‘You know movement and you know my body better than anyone,’ ” Spitz said in his San Ramon gym after finishing a workout just feet away from 2019 Pan American Games gold medalist and 2020 Olympic weightlifting hopeful Wes Kitts. “So we set out on this journey and I just learned on the fly. T.J. performed well and was drafted in the second round. Ultimately that’s how the whole process started. … I never wanted to be in the business. It was basically forced on me.”

Now it’s a major revenue stream.

While combine-specific training programs can be traced back to the early 1990s, it was about a decade later when such camps reached a level where most of the combine attendees were using them. Now it’s nearly impossible to find a player in Indianapolis who didn’t attend one.

There are several large facilities in Arizona, Florida and California, in addition to boutique spots like California Strength, which is also working with several non-combine invitees to get them ready for various pro days on their college campuses.

Agents such as Steve Caric of Caric Sports Management in Las Vegas are mostly responsible for placing their clients in the right programs and financing their training and living expenses for an average of eight weeks between the end of their college season and their first NFL contract.

Caric, who has worked closely with Spitz in helping the curriculum evolve to where it is today, says the program for his six combine invitees will run him an average of $20,000 per player.

Better housing and car allowances, along with promises of spots at elite facilities, are used by agents as recruiting tools to sign the best college prospects.

Caric said the investments have grown so massive that agents have to be more selective in who they sign to ensure they are able to recoup their stake.

Atlanta Falcons tight end Austin Hooper, who has trained at California Strength since high school and did his combine prep there, said he couldn’t imagine having gone through the draft process without the combine-specific training he received.

“It’s really hard to prepare for unless you really put in the hours and time to get better,” he said last week after a workout with the college players. “It’s a skill. It’s not about football, it’s about doing the drills the best you can so you have to study for it and prepare for it.

“It’s such an intense process, just with the amount of hours the whole combine entails. Just being there in Indianapolis, going for days only sleeping three or four hours. It’s a miserable experience. Everyone wants to be a part of it until they’re a part of it. Then they realize how tough it is.”

The mind

Fatigue and overstimulation aren’t the only challenges for the brain to overcome at the combine.

Teams want to know the prospect they are drafting is not only the right kind of player but the right kind of person.

The Wonderlic test that is administered at the combine is a well-known measure of a person’s ability to learn and solve problems. Each player going through the pre-combine training is offered instruction on taking the exam.

Perhaps a more important and involved part of the training is prepping for the interview process.

Each team puts players through rigorous interrogations, so Spitz brings in a former NFL executive to replicate the scenario in the weeks leading up to the combine.

Stanford linebacker Casey Toohill, another combine invitee, learned there is far more to it than just knowing the answers to a test.

“It’s basic things like sitting up straight, being engaged, not looking tired,” he said. “But it’s also a step further in terms of gaining insight into what they’re actually looking for with these questions. You can know how to answer a question, but you might not know what the person asking the question is looking for in your answer. … There can be different types of questions that you may not have experience fielding. It’s good to be able to go through that.”

Caric said teams will try to challenge the players to see how they react to pressure and agitation. He reminds his clients their actions will be scrutinized 24 hours a day while they’re in Indianapolis.

The teams know every player has specifically trained for how the week is going to play out, both on and off the field. A player who shows up unprepared for any of the various scenarios could be sending a signal he isn’t committed to his craft.

“The combine process isn’t about one thing,” Caric said. “It’s not just about running fast or crushing the interviews. There’s thousands of kids eligible for the draft and each team has an average of seven picks. These scouts are looking for a reason to take you off their list, not move you up. So your tape is the start. You have to have good college tape. You have to be injury-free. But the next step is the combine and the pro day. Your numbers do matter.

“If you’re a great tester and not a great football player, that’s not enough. But if you don’t complete the puzzle for the teams, you don’t have a chance to get drafted as high. So it’s paramount.”

The body

One of the key phrases Caric highlighted was “injury-free.” The first two days of the combine mostly consist of medical personnel from the NFL and its individual teams examining every square inch of each player’s body to make sure there are no red — or even yellow — flags.

Spitz and Caric don’t want any surprises either, so the combine training begins with full medical exams of each attendee.

Once that’s out of the way, the process of fine-tuning the body can begin.

Players get in field and gym work six days a week to improve strength and speed.

Spitz believes the average player can trim three-tenths of a second off their 40 time and add an average of five reps in the bench press.

“The bottom line is these are elite athletes,” Spitz said. “These are not guys like me training in this manner. They’re guys that have what we call a high baseline, but also tend to be high responders. So they start at a high level and then we apply training to them and they achieve very good results over a very short time horizon.”

In addition to preparing to master the specific drills at the combine, players work with individual coaches to hone their craft on the field and better understand what pro personnel want them to know about playing their position.

They spend time training in boxing and mixed martial arts to improve their hands and work on winning individual battles.

The hard work is offset by state-of-the-art recovery tools. Attendees get regular massages as well as cryotherapy, compression therapy, stim treatments, muscle activation therapy, dry needling and are offered regular yoga and sauna sessions to help ensure the body’s readiness to get back to work.

There is also regular access to a physical therapist who just may be one of the secret weapons of the program.

The guru

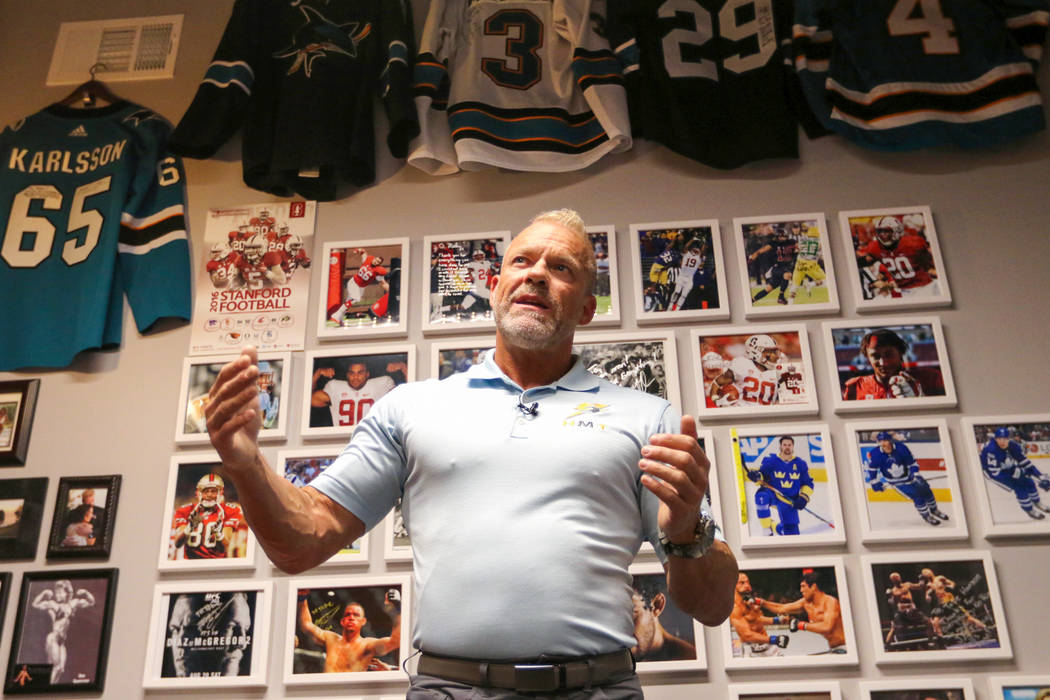

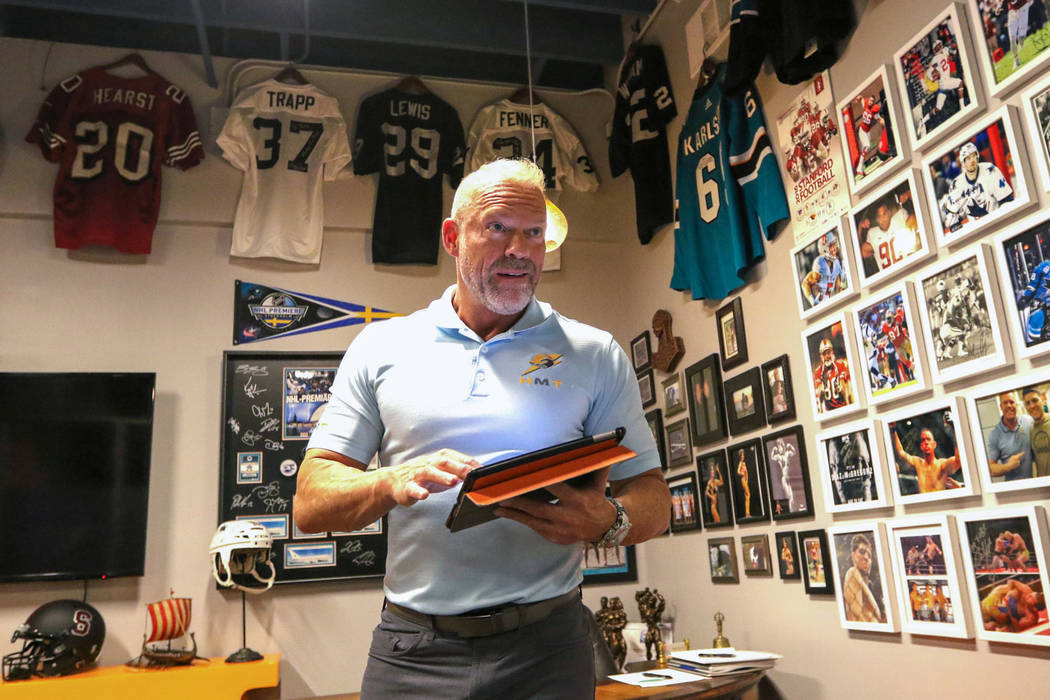

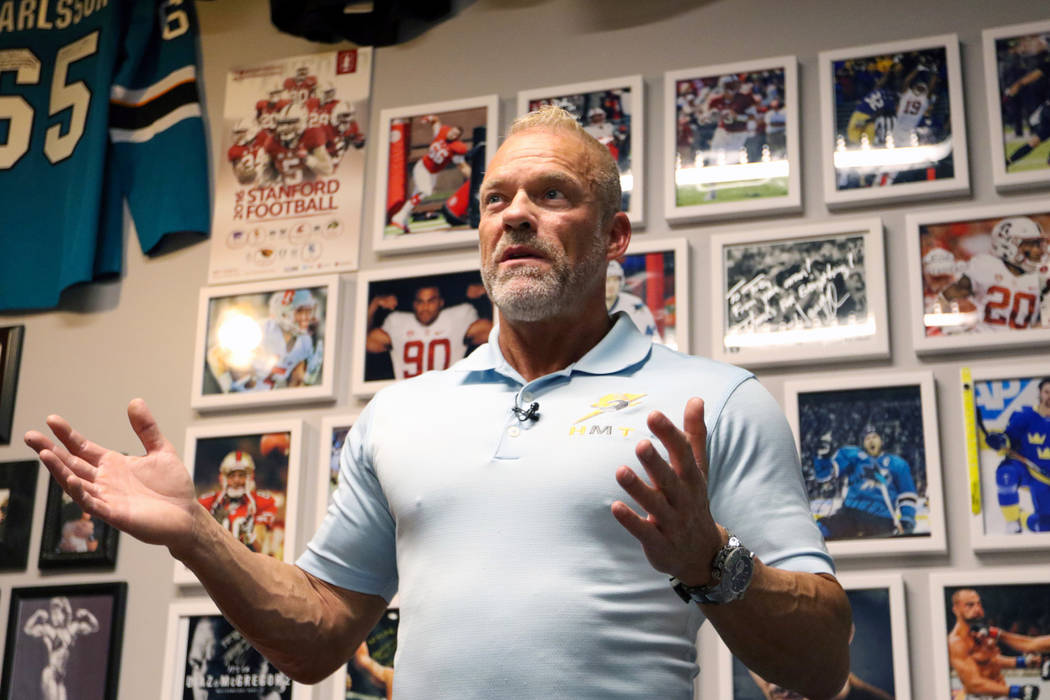

Tobe Hanson is a physical therapist by trade, though he’s not a big fan of labels.

The number of pictures of prominent Bay Area athletes on his wall who are and have been his clients may only be surpassed by the number of words that have been used to describe what he does.

Guru, svengali, life coach, motivational speaker — Hanson has heard it all.

“The interesting thing is you can’t really put a title to what I’m doing because I’m basically working on removing physical pain, mental strain and helping a person perform better,” Hanson said. “There’s cause and effect in everything. Nobody has pain for no reason. Performance is cause and effect, too. So by teaching them about what they’re doing in their lives and the patterns they have and how that influences the healing as well as their performance, they’re able to learn and make changes.”

As he works out tension in Stanford running back Cameron Scarlett, who was not invited to the combine and is preparing for his pro day on campus, Hanson softly tells him to envision what it will be like to hear an impressive 40 time read aloud and what it will look like on the stopwatches of the scouts.

Tight end prospect Devin Asiasi, who is entering the draft after his redshirt junior season at UCLA, credits Hanson for helping calm his nerves going into the combine.

“Tobe talks to us about being present and not obsessing over the future or getting caught up in your past,” Asiasi said. “We have so much on our plate and there’s so much pressure, but listening to his philosophies and staying present and controlling what I can control each day is going to keep me ready to do what I need to do.”

That also required him being able to better fuel his mind and body.

The food

Meals for each attendee are prepared daily by a chef for each of their dietary needs.

Some players need to lose weight while others need to put on a few pounds to fill out their frame before their bodies are evaluated at the combine.

Most importantly, each player goes through an assessment to determine how to best feed their particular body chemistry.

“We spend a lot of money crafting their nutrition plans. Then we have a chef that prepares each and every meal according to what I want from an energy allowance standpoint and a macronutrient standpoint,” Spitz said. “Everything we do works together in this holistic fashion. That’s what ultimately gives us the results.”

Some players were already familiar with proper nutrition and were putting that knowledge into practice.

Asiasi admits he was lacking in that area.

“In college, I didn’t do as good of a job with nutrition,” he said. “With school and practice, you’re always rushing to get something to eat, so I was always hitting Burger King or Carl’s Jr. or something. But I’m so focused now on the task at hand. I feel like my body composition has been improved greatly through this process.”

So has his technique in the drills.

The field

A pair of local parks play host to the athletes at 10 a.m. each day. There they alternate between lateral and linear work in preparation for the drills they will run in Indianapolis or at their pro days.

But the key to mastering the drills isn’t just moving faster.

Lines are marked off when practicing the 40 to show exactly where each step should be taken in order to take an optimal number of strides.

There are cameras and sophisticated timing devices monitoring every rep for later analysis.

This is also where the camaraderie can be observed. While the players are individuals in pursuit of their own dreams, they also share the common bond of preparing for something few people will ever experience.

NFL standouts Zach Ertz and Kiko Alonzo remain good friends after going through this process together in 2013. They often work out together in the offseason at the facility.

Bonds have formed in this year’s class as well.

After Georgia running back Brian Herrien ran a particularly good 10-yard split, he referenced the famed Chris Johnson 4.24-second 40 time from 2008. Washington State quarterback Anthony Gordon immediately went to his phone to look up Johnson’s ridiculous 1.43-second 10-yard split to rib Herrien about how far he still had to go.

The laughter had barely subsided when talk turned to a scheduled group outing for the next day.

Final preparations

Asiasi, polite and soft-spoken, bristled at Spitz’s proclamation they would be hitting a barbershop together the next day with less than a week to go before the start of the combine.

“Nobody’s touching my hair,” he said. “I look good.”

His fellow combine preppers weren’t about to let that slide.

Spitz said nobody would be forced to cut their hair, but the option was there for anyone looking to clean up before sitting in front of all the NFL folks in Indianapolis. There was also talk of a tailor taking measurements.

It’s all part of the all-inclusive preparatory program that leaves no stone unturned or weight unlifted.

Two hours later, Tomlinson was getting out of his final float session before leaving for the combine.

He said he was relaxed and focused. More importantly, he was prepared for the biggest job interview of his life.

“I’m just ready to go, man,” he said.

Contact Adam Hill at ahill@reviewjournal.com. Follow @AdamHillLVRJ on Twitter.

NFL Scouting Combine

Who: Invited college players who are draft eligible

When: Sunday through March 1

Where: Lucas Oil Stadium, Indianapolis

TV (NFL Network): Thursday, 1-8 p.m. (QB, TE, WR); Friday, 1-8 p.m. (OL, RB, PK, ST); Saturday, 1-8 p.m. (DL, LB); March 1, 11 a.m.-4 p.m. (DB)

Measurable drills at NFL Combine

40-yard dash — Pure test of speed and explosion from a static start, athletes are timed at intervals of 10, 20 and 40 yards.

Bench press — Measure of how many times an athlete can lift 225 pounds

Vertical jump — How high can an athlete jump from a flat-footed start?

Broad jump — Similar to the vertical jump, but the distance is measured outward instead of straight up.

Three-cone drill — Timed drill that helps demonstrate an athlete's ability to change directions and maintain speed. It's also known as an L drill due to the shape the cones are set up in.

Shuttle run — Measure of lateral quickness in short areas, also known as a 5-10-5 drill because the athletes start in a 3-point stance and go five yards to the right, 10 yards to the left and five more yards back to the center.