Proper use of neck hold not fatal, research shows

The safety of a controversial neck hold taught to police officers to subdue unruly suspects is backed by a growing body of scientific research, but so many fatalities have been blamed on its use that many law enforcement agencies have banned it.

It’s an issue confronting Las Vegas police, who on Nov. 3 used a neck restraint to subdue an agitated 29-year-old man who died in custody. The Clark County coroner has yet to determine the cause of the man’s death, but since 1990, at least four people have died after Metropolitan Police Department officers used, or tried to use, a neck hold on them.

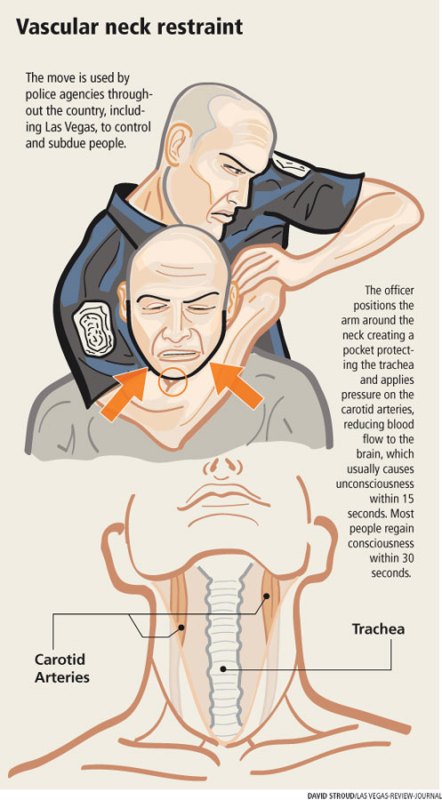

The move in question is the vascular neck restraint, which is referred to in the martial arts world as the sleeper hold. It compresses the carotid arteries on the sides of the neck, restricting blood flow to the brain and causing the subject to pass out.

The Los Angeles Police Department was forced to stop using it in the early 1980s after the technique, also known as the carotid restraint, was blamed in the deaths of several people.

But a growing body of evidence shows that, when executed properly, the neck restraint is not lethal. And according to one study, the neck restraint has been wrongly blamed for causing a number of deaths.

The research has won over at least one former critic.

In 1990, after the most controversial police-related killing in Las Vegas, self-defense tactics expert John Peters told the Las Vegas Review-Journal that the carotid restraint "should only be used in a life-or-death situation."

The hold, which Las Vegas police then were not formally trained to use, was blamed in the death of a 39-year-old man. Peters was a consultant for the Secret Service at the time.

Peters now operates the Institute for the Prevention of In-Custody Deaths, a think tank and training center in Henderson. His opinion of the vascular neck restraint has changed.

"It’s not nearly as controversial," Peters said this month. "Generally, vascular neck restraints today are considered pretty safe."

The centuries-old technique traces its roots to the Asian martial arts community. There are several variations of the vascular neck restraint. All are based on placing pressure on the carotid arteries, which carry blood from the heart to the brain, and reducing blood flow. Although blood is still reaching the brain, the amount is not enough for the subject to maintain consciousness.

Most law enforcement agencies that sanction the use of a neck restraint, including Las Vegas police, use the Lateral Vascular Neck Restraint, a hold trademarked by the National Law Enforcement Training Center in Kansas City, Mo. The method teaches officers to place an arm around the subject’s neck, forming a "V" in front of the subject’s chin. The officer then squeezes, placing pressure on the subject’s carotid arteries.

When done properly, the subject’s trachea is unaffected and his breathing is uninterrupted. The technique is often called a "chokehold," but that term is incorrect. A chokehold places pressure across the front of the subject’s neck, blocking or damaging the trachea, which can be deadly. A subject should not choke when a neck restraint is applied.

Applying the neck restraint for between seven to 15 seconds will consistently render a person unconscious. Most people regain consciousness within 30 seconds.

The method is painless, said Brian Kinnaird, a former police officer and criminal justice professor who operates Forceology, a Kansas-based consulting company. Kinnaird has applied the restraint in controlled and uncontrolled settings. He has experienced it six times in controlled settings.

"There’s no injury associated with it," Kinnaird said. "No pain, no marks. What’s not pleasant is losing control."

The experience is similar to being put under anesthesia. When the subject wakes, "it’s as if half the afternoon has passed," Kinnaird said.

In the 40-year history of the Lateral Vascular Neck Restraint, there has never been a serious injury or death caused by the technique, said Charles "Chip" Huth, a Kansas City Police Department sergeant and vice president of the National Law Enforcement Training Center, where the technique was developed. More than 500 police departments in North America have certified instructors that teach the Lateral Vascular Neck Restraint.

The technique is not just used to render a person unconscious. The vast majority of the time, the subject surrenders before that happens, Huth said, adding that only 3 percent of incidents result in a subject losing consciousness.

One of the most comprehensive studies on neck restraints was done by the Canadian Police Research Center. The center interviewed doctors and police experts. It reviewed case studies. It recommended the technique not be used on children, the elderly, visibly pregnant women and those with Down syndrome.

The center’s report found that while no restraint method is completely risk-free, "there is not medical reason to routinely expect grievous bodily harm or death following the correct application of the vascular neck restraint."

Las Vegas police began training officers to use the Lateral Vascular Neck Restraint in 1991, a year after one of the department’s vice officers killed 39-year-old Charles Bush while using a neck hold not sanctioned by the department.

The department now requires officers to undergo 16 hours of training on the technique before using it and four hours of recertification training every year. Officers are allowed to use it during arrests and when defending themselves. A use-of-force report must be completed each time it’s used. As of mid-November, Las Vegas police had used the Lateral Vascular Neck Restraint 66 times this year.

At least four Las Vegas officer-involved fatalities have been preceded by the use of the vascular neck restraint:

• In 1990, a medical examiner determined that Bush, a drug user, died from heart failure because of a choked carotid artery.

• In 2001, 33-year-old French national Philippe LeMenn, who was mentally ill, died from asphyxiation because of restraint while being subdued in the Clark County Detention Center.

• In 2006, robbery suspect James Lewis, 37, died from cocaine intoxication, with police restraining procedures and a heart ailment also contributing to his demise. Family members said police attempted a "chokehold" on Lewis while he was resisting arrest.

• The Clark County coroner’s office has not yet determined why Dustin Boone died on Nov. 3. Las Vegas police had gone to Boone’s home near Tropicana Avenue and Buffalo Drive because a social worker reported that he had been behaving erratically and was not taking his medications. During a struggle, an officer used the neck restraint on Boone and he later died.

The North Las Vegas and Henderson police departments do not train their officers to use any sort of neck hold.

The Canadian study blamed deaths associated with neck restraints instead on "excited delirium," a controversial concept of how some people die during altercations with police. The condition has not been recognized by the American Medical Association, but it recently was recognized by the American College of Emergency Physicians.

People in a state of excited delirium initially appear "agitated to grossly psychotic, and exhibit feats of superhuman strength, especially during attempts to restrain them," according to an article posted on the American College of Emergency Physicians’ Web site.

Shortly after being restrained by police, those in a state of excited delirium appear to cease struggling and begin breathing in a labored or shallow pattern, according to the article. The person is usually dead moments later.

Alan Lichtenstein, general counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union of Nevada, is skeptical of the concept. The idea that police intervention doesn’t contribute to the death of someone with excited delirium is "nonsensical," he said.

"Yes, people in agitated states may be much more vulnerable to death or serious injury if they are hit by a Taser or other police action," he said. "But what that says to me is people who are agitated probably should be looked at more carefully by police, not less carefully."

He said the use of vascular neck restraints should be carefully reviewed or abandoned.

"I think that to the extent that other police departments seem to be able to do quite nicely without it, it probably should be abandoned," Lichtenstein said.

Many police departments have banned the use of neck restraints because of the liability involved. Police departments have had to settle many civil lawsuits involving neck restraint-related deaths.

"Unfortunately, we see policies driven by fear of lawsuit a lot," Huth said.

Neck restraints have proven to be costly for Las Vegas police.

Bush’s family won at least $1.1 million after suing the Las Vegas police and Clark County. LeMenn’s family won $500,000 in a lawsuit against the department and an undisclosed amount from the Clark County Detention Center’s health care provider.

Review-Journal writer Brian Haynes contributed to this report. Contact reporter Lawrence Mower at lmower@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0440.