Tomato cans ripe for picking

Willie Chapman was fuming.

The 39-year-old heavyweight had just lost a 10-round split decision to Carlos Barnett, squandering possibly his final chance at glory.

"Damn it!" Chapman screamed inside his makeshift dressing room at The Orleans. "Why?"

Then he broke down and cried. He didn’t want to sign for his purse, which was $4,000 minus a $120 sanctioning fee to fight for the IBA continental heavyweight title.

He didn’t want to go to Valley Hospital for an exam. It wasn’t until ringside physician Dr. Rodney Courson threatened him with an indefinite suspension that Chapman agreed to go.

"Nothing works out for me," Chapman said. "Nothing works out. My heart is crushed. Crushed."

At 21-29-4, Chapman has had more than his fair share of tough luck inside the ring. The most money he has made for a fight was the night he lost to Lamon Brewster in 2002 at Mandalay Bay. Chapman was knocked out in the sixth round and made $12,500.

But the competitor in him refuses to quit fighting.

During his 12-year career, Chapman never gave up his dream of winning a title. Any title. But on this January night at The Orleans, Chapman lived up to his "Wreckless" nickname. He left himself open and was knocked down in the second round and twice more in the sixth.

Had he stayed on his feet, he might have won that elusive title.

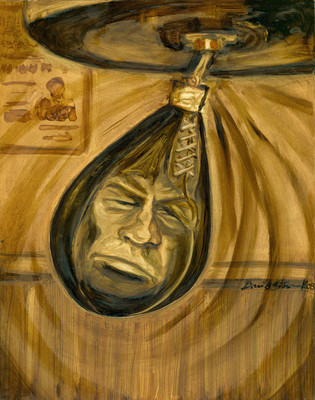

Instead, it was another loss for a boxer who at one time would have been known as a "tomato can" because of his lopsided record.

Today, those types of journeyman fighters — fighters who will take a bout on short notice knowing they have little or no chance of winning — are hard to find. Licensing regulations have been tightened, and greater scrutiny is being given to ring records, medical history and whether a fighter can be competitive.

State boxing commissions work together hoping to eliminate some of the chicanery of the past, like when Bruce "The Mouse" Strauss fought twice on one night in Omaha, Neb.

Strauss was knocked out in his first appearance that night, changed trunks and came back later for the second fight. When officials asked him if he hadn’t already competed that evening, Strauss said, "Nah, that was my twin brother, Bruce ‘The Mouse.’ I’m Bruce ‘The Moose.’ "

Strauss got knocked out in that fight, too. But he boasted that he was the only fighter that night to get two paychecks.

A DYING BREED

Boxing historian Bert Sugar defines a tomato can as "a guy who is picked because he has no chance of winning, but he looks good doing it."

Sugar said the tomato can is not as common as in the 1950s, ’60s and even the ’70s when fighters such as Chuck Wepner, Jordan Keepers, Jim Wisniewski and Peter McNeeley laced up their gloves and took on anybody.

"They still exist," Sugar said. "Mostly in the small club fights in the Midwest. You don’t see it in the main events, but more in the four- and six-rounders” where it’s easier to overlook them."

But in the high-profile boxing states, even the smallest club cards are under increased scrutiny. Nevada, in particular, has taken a tough stand when it comes to licensing unqualified fighters who are not competitive.

It goes back to the 1980s when Chuck Minker was executive director of the Nevada Athletic Commission, and that trend continued under Marc Ratner.

"Chuck started tightening up the regulations," Ratner said. "He tried to stop the mismatches.

"It’s hard for that type of fighter to get licensed anymore — certainly in Nevada. The liability factor is too great. Nobody wants blood on their hands because they licensed a guy who had no business being in the ring."

Keith Kizer, the current executive director of the commission, said safety and competition are the main issues that determine whether to allow a fighter to compete.

Kizer says the fighter’s overall record is important, as is his recent record. Knockout losses also are scrutinized.

"Some guys don’t have the skill level to compete," Kizer said. "Some guys have the skill, but their medical condition is such that he’s a health risk."

NOBODY’S PERFECT

The Internet is a great tool for Kizer to research a fighter’s record before licensing.

But Kizer admits he’s not perfect. Once in a while he’ll second-guess himself when it comes to licensing a fighter. On Jan. 5, 2007, Donnie Orr, a promising middleweight, was scheduled to fight Mikhall Lyubarsky at The Orleans. Orr was 6-0, and Lyubarsky was 3-7.

Kizer wasn’t overly concerned that Lyubarsky had a losing record. But upon closer inspection, Kizer noticed that in Lyubarsky’s seven losses, he was knocked out in either the first or second round.

Still, he gave the promoter, Frank Luca of Crown Boxing, the benefit of the doubt and approved Lyubarsky. Orr scored a first-round knockout, and afterward it was learned Lyubarsky had tested positive for marijuana.

Records can be misleading. Fighters also build their records fighting stiffs.

John O’Donnell, a welterweight from England, was brought to Las Vegas to fight on the undercard of the May 5 fight between Floyd Mayweather Jr. and Oscar De La Hoya at the MGM Grand Garden. His opponent, Christian Solano, had an 11-12-1 record.

Kizer’s objection wasn’t with Solano, who had proved to be a competitive fighter despite his losing record. His issue was with O’Donnell.

The Englishman was sporting a 15-0 record. But upon closer inspection, his record was built at the expense of bums whose combined record was 106-459-2, including one fighter, Ernie Smith, who was 13-109-5.

Solano scored a technical knockout at 1:50 of the second round.

Kizer said he still thinks he made the right call in allowing the Solano-O’Donnell fight to take place. But he does have second thoughts on allowing the Lyubarsky-Orr fight.

"It’s impossible to judge a fight beforehand," Kizer said. "The O’Donnell fight shows that you can’t go on overall record alone. I still thought O’Donnell could hold his own.

"The Lyubarsky fight showed there are other intangibles you don’t know. How did we know he would come in while under the influence of marijuana? Neither his trainer nor I would have let him fight."

LICENSE TO LOSE

Arnold Sam lived in Yerington for much of his career, which ran from 1978 to 1991. A heavyweight, he was 6-27-2, losing 10 fights in a row at one point.

Kizer admitted it would be tough to license someone like Sam today.

"With someone with a similar record of Sam’s, you have someone who has a poor (overall) record and had only won two of his last 20, it would make it hard to allow someone like him to fight," Kizer said.

For the matchmakers, it can be equally tricky as they attempt to get fighters into the ring.

"Everything is relative," said Bruce Trampler, Top Rank’s head matchmaker since 1981. "You put a guy in a 10-rounder here in Las Vegas, and he’s an opponent. You put the same guy in a six-rounder in Idaho, and he’s a main-event guy.”

Trampler said making matches today is difficult because of the boxing commissions.

"It’s the same song and dance — they all talk about the safety and the health of the fighters and the competitiveness of the fight," Trampler said. "But we’re not here because we make mismatches. We don’t want to see a fighter get hurt any more than they do. If I’m putting on (expletive) fights, then pull my license."

Trampler said a fighter’s record can be deceiving.

"I can find a guy who’s 6-10 who can beat a guy who’s

16-0," he said. "But I wouldn’t be able to find a commission to license the 6-10 guy because they’ll look at the records and say it won’t be a competitive fight."

Luca, who doesn’t have Trampler’s budget, said he understands why Nevada and other states don’t license some fighters.

"I respect the position (Kizer) is in," Luca said. "Keith is fair, but he’s also tough. I’m an old fighter myself, and the fighters’ safety should always come first, absolutely."

Luca said he often has to scramble to find opponents to make his fights competitive.

"There’s no question the financial side makes it doubly tough for promoters like me to make competitive fights," Luca said. "But the Nevada commission is probably the best in the world. Their standards are high. As a matchmaker, I have to comply."

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

Bring up the tomato can notion to Kizer and Trampler, and both get defensive.

"I long ago gave up using that term because I have too much respect for what these guys do," Trampler said. "They take real punches. They hurt like everyone else."

Said Kizer: "I don’t like that term. I think it’s a derogatory term. I also don’t like the terms ‘opponents’ or ‘underdogs’ because it underplays the seriousness of it all.

"That said … there are fighters who should not be fighting."

While tomato can fighters might be disappearing, the journeyman still thrives. Unlike a tomato can, who comes into a fight knowing he’s going to lose, the journeyman not only believes he can win, he sometimes does.

That’s why boxers such as Chapman step into the ring. Despite being an underdog, he will battle and make the other fighter work for his victory.

"No one’s ever called me a tomato can," Chapman said. "I’m fighting Olympic-caliber fighters, and they don’t knock me out. I win my share of fights. Even when you lose, and you know you gave it all you had, and to hear the fans boo the decision when you know you won, that’s a good feeling.

"If you call me up, I’m going to put on a show. I’m going to entertain the fans. I’m going to give you my best effort."

Chapman played football at Weber State. He started boxing after one of his teammates challenged him to a fight. He is self-trained, self-managed and self-promoted. To pay his bills, he has been a security guard, a used-car salesman, a furniture mover and a substitute teacher, and he has trained other would-be boxers.

"I know I’m up against it most of the time," Chapman said. "But I’m never jealous of the other fighters. I understand what the deal is. But that doesn’t mean I have to cooperate and lose. I may lose, but it’s on my terms. If I go down, I go down fighting. That’s why promoters still call me up and use me, because they know I’m going to give them a great effort."

Trampler says Chapman puts on a show and certainly is no tomato can.

"The guy comes to fight every time," Trampler said. "He can be a dangerous guy."

SORE LOSER

Reggie Strickland is a different story.

According to boxrec.com, a Web site that tracks the professional records of fighters, Strickland has fought professionally 363 times, sometimes under the aliases of "Reggie Buse" or "Reggie Raglin."

His record?

Sixty-six wins, 276 losses, 17 draws.

Strickland claims he was robbed in a lot of his losses.

"Here’s the deal," Strickland said from Indianapolis, where he is training his sons, Ryan and Brian, to box. "I’ve had more fights stolen from me than I lost. At least a hundred."

Strickland scoffs at being called a tomato can.

"That’s bull," said Strickland, who said the most he made in one night was $6,500. "It’s a tag. That’s all it is. I’ve been in over 300 fights, and I got knocked out what, only 25 times? How does that make me a tomato can? I didn’t lay down for no one."

Strickland hasn’t fought since 2005, when he was in an auto accident. Despite being 39, he still has the urge to fight, but the Indiana Athletic Commission wants him to undergo a complete medical evaluation.

John McCane, one of three members of the Indiana commission, said given Strickland’s inactivity and his record, the commission would take a long, hard look before letting him fight in that state again.

"It’s one thing to be licensed," McCane said. "It’s another to be allowed to fight."

"(Expletive) that," Strickland said. "I’m still involved in boxing, even though boxing screwed me. I think about all those hometown decisions I lost where the judges screwed me, and it pisses me off.

"I won’t lie to you: I still miss it sometimes. But boxing’s always been a part of me, and it always will be."

COLORFUL NOVELTY

While Strickland won’t admit he’s a tomato can despite his odious record, Strauss might be willing to accept the tag.

The fighter who lost two bouts in one night has an official record of 76-52-5 with 54 knockouts. But he claims there’s about 200 more fights unaccounted for, mostly losses. He competed in eight weight classes, from 135 to 175 pounds, and last fought officially in 1989.

"Mouse wasn’t your journeyman fighter," Trampler said. "He wasn’t a tomato can. He was more of a novelty act."

Strauss’ colorful life was captured in the 1997 film "The Mouse," which starred John Savage, Burt Young and Rip Torn.

In a 2003 New York Times article, Strauss was described as the most ”successful sacrifice” to grace the ring. The article said Strauss boasted of having been knocked out at least once on every continent except Antarctica.

Slipping under the radar of various state commissions with fake names such as Pretty Boy Bernstein, Ruben Bardot and Machine Gun Jones, Strauss often fought three times a week.

”If I couldn’t knock ’em out,” he once said, "I’d look for a soft spot on the canvas, wait for a big punch and close my eyes.”

In a story in the Home News & Journal (East Brunswick, N.J.), Strauss said he never expected to win a title but only to "have fun, make some money and see the world." Unlike many other human punching bags, Strauss relished his role as "world’s worst boxer" and did see himself as a "tomato can."

On July 17, 1980, Strauss fought an up-and-coming middleweight named Bobby Czyz, according to a 1996 story in the Home News & Journal.

In front of a cable TV audience, Strauss put on a show before he suffered a fourth-round knockout. The next night, in Nebraska, Strauss knocked out a fighter named Nick Miller.

"On my way in the ring, a fan yelled out, ‘Hey, I saw that bum get knocked out on TV last night,’ " Strauss told the New Jersey newspaper. "I said, ‘That was my brother, I’m The Moose.’ "

Strauss said in an interview with CBC Television in 1986, "I’m the last of a dead breed."

He was speaking for tomato cans everywhere.

Contact reporter Steve Carp at scarp@reviewjournal.com or (702) 387-2913.