COMMON GROUND

Roy and Betsy Miller cringed at the sight of fresh vehicle ruts that left a zig-zag scar on what had been a picturesque Mojave Desert hill off a dirt road that leads to the historic mining town of Gold Butte.

"This area was pristine and untouched as it had been for thousands of years," Roy Miller said on a back-roads trip this month, recalling how only a few days before there were no ruts on the hill.

"On the other side there are motorcycle tracks that go up and down," he said. "There are dozens and dozens of examples like that out here."

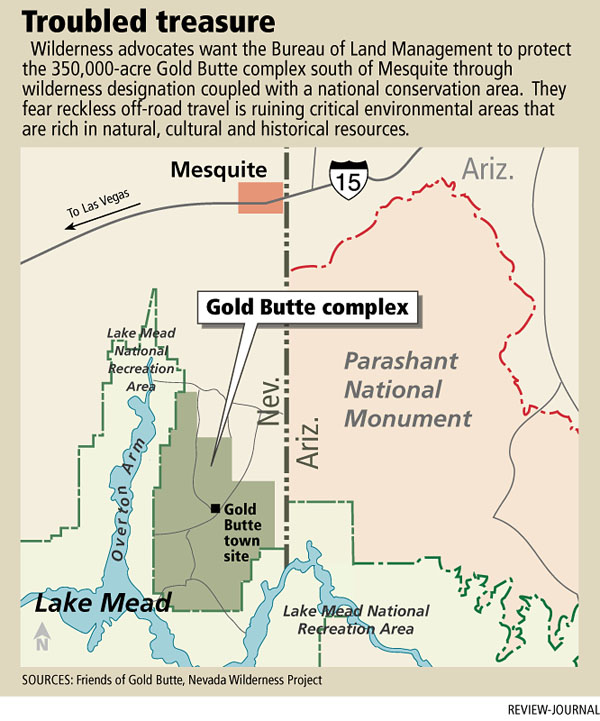

That's why the Millers, who are members of Friends of Gold Butte, and other Nevada wilderness advocates want the Bureau of Land Management to consider protecting the remote area, south of Mesquite and 65 miles northeast of Las Vegas, through an arrangement that couples wild lands with a national conservation area.

BLM officials also have been trying to get a local rancher to remove cattle and equipment from a grazing allotment that was canceled in 1994 to protect habitat for the threatened desert tortoise and other sensitive species.

If the wilderness advocates' campaign is successful, Southern Nevada then would have a third national conservation area in addition to Red Rock Canyon and Sloan Canyon, on the western and southern rims of the Las Vegas Valley.

Their visit was timed with the release of a report by the Campaign for America's Wilderness. The report lists Gold Butte as one of 10 "treasures in trouble" that are at risk of losing their wild nature because of increased population pressure from urban areas in the various regions.

"A national conservation area with wilderness would help to protect some of the wild areas while also designating other areas for recreation where it is appropriate to take vehicles," said Reno resident Carrie Sandstedt, the campaign's national field director.

Since the Millers moved to Mesquite from Ohio in 2001, they have seen Gold Butte's critical environmental areas steadily degrade through reckless off-road vehicle and dirt bike use. They feel that off-roaders who don't stray from established roads and trails can coexist with others who want to hike through the area and enjoy its natural, cultural and historical resources.

"Why can't they designate areas for off-roading?" Betsy Miller asked. "We were told it's because it's designated as an ACEC," an area of critical environmental concern.

Off-roading is prohibited in these sensitive areas where rare plants and desert tortoises live. The terrain in many places is scarred by off-roaders who use it regardless of the prohibition and despite some 30 volunteers who monitor Gold Butte as site stewards for the BLM.

Signs that mark the protected areas have been yanked down, and BLM officials say they can afford only one ranger to patrol Gold Butte.

The bureau's Las Vegas field office has little funding to constantly clean up and repair damaged areas.

Nevertheless, the BLM has completed an inventory of ancient rock art and other American Indian cultural resources. This year, the bureau will issue a contract to document Gold Butte's wildlife and botanical habitats.

The BLM has proposed keeping 480 miles of roads open in the Gold Butte complex and closing 70 miles.

Nancy Hall, Gold Butte coordinator for the Nevada Wilderness Project, believes a 32,000-acre swath known as Mud Hills, for example, could be designated wilderness "and you wouldn't have to close a road. I don't think there's any argument not to designate it wilderness."

The Millers joined Hall in exploring Gold Butte's scenic and historic sites and to discuss their hope for protecting them.

"If we don't get protection for this place, it won't be there for your grandchildren and your great grandchildren," Roy Miller said.

Said his wife: "It makes us sad to see what's happening. It's almost like losing a friend.

"We know it can't stay pristine forever but it needs management. We understand there are people who are anti-government."

Among those who object to the federal government's management of the public land is longtime rancher Cliven Bundy.

For 14 years, he has bucked the BLM's authority and continued grazing cows in the area. His grazing lease for the Bunkerville allotment was canceled in 1994.

Bundy, 62, said at the time he didn't think the bureau is the proper landlord of public lands in Nevada. His family has run cattle on the range since 1877.

Reached on Thursday, Bundy said his position hasn't changed.

"My pre-emptive rights have stood strong for over 14 years since I fired the BLM from managing my ranch," he said.

Despite his resistance to removing the cattle, the BLM notified him on April 2 that his range improvement permit is canceled and he has 180 days to remove wire, fence posts and other debris. Creating a national conservation area, as envisioned by wilderness advocates, would continue to prohibit cattle grazing.

On April 16, about a half dozen cows were seen in an area burned by a lightning-caused wildfire in 2005 that the BLM is trying to rehabilitate.

Last fall, dozens of cattle roamed the same area where some responsible off-roaders, the Southern Nevada Land Cruisers, were asked to pay nearly $5,500 to hold a camp-out and rally, 60 times more than they had paid for past events in which they stayed on roads and used their trucks to haul out trash left by others. Instead of paying, they canceled the event.

Much of the increased cost was for paying the BLM to process the permit and monitor the group's activities in Gold Butte's sensitive riparian areas, some of the same areas where Bundy's cows have roamed while the BLM spent more than a decade to reverse the impacts of grazing.

But cattle have played a role in Gold Butte's mining history dating to the 1730s when Spanish explorers camped in the area, according to Gold Butte historian John Lear.

Evidence of their presence has been found in the form of two 20-foot-diameter rock slabs, called "arrastras," that were used for crushing gold and silver ore. Horses or mules would walk around the slabs dragging stones to pulverize the ore. The resulting fine-grain mud was then processed into gold or silver bars.

Mormon settlers came to the area in the mid-1800s, followed by prospectors who established the Gold Butte mining town in the early 1900s. The town of about 1,500 people had a post office in 1907, but the lack of quality in ore diminished, as did the town's population in 1910.

Lear said copper from the Tramp Mine and the Grand Gulch Mine in Arizona kept the Gold Butte area busy. As many as 100 hundred ore wagons at a time pulled by oxen and mules passed through the area from 1915 to 1917 to deliver copper to a rail spur at St. Thomas for use in World War I.

Two miners are buried at the old town site, Art Coleman and Bill Garrett, who lived at Gold Butte from the early 1900s until their respective deaths in 1958 and 1960. Garrett was the nephew of Pat Garrett, the sheriff who killed Billy the Kid at Fort Sumner, N.M., in 1881.

Lear said he doubts Gold Butte will become a national conservation area because of the effort involved and the potential opposition from off-road vehicle enthusiasts.

"There's no chance. I wish good luck to them. They have the best intention," he said Friday about wilderness advocates. "I understand both people's position. They want everybody on one road, and it ain't going to happen."

From an off-roader's perspective, what the wilderness advocates define as a road or vehicle trail is different than what many off-road enthusiasts think they are.

Ken Freeman, past president of Southern Nevada Off-Road Enthusiasts, said in the eyes of wilderness advocates and environmentalists, these roads and trails are mechanically groomed, or graded. "Ninety percent of the trails in Nevada aren't mechanically groomed."

Turning some of these critical areas of environmental concern into wilderness would also eliminate them from the realm of places where solar and wind energy could be developed, Freeman noted.

As it is now, the protections for the areas is "one notch below wilderness," with seasonal limits on when off-road travel is allowed.

Freeman acknowledged that there might be "a few bad apples" in the off-roading crowd who have no regard for signs or laws that protect these areas from damage and continue to scar the terrain, but he said that's going to continue to happen if the land is designated wilderness.

"The majority of the users are concerned with the environment," he said Thursday. "We need to give these people a place to recreate."

What Nevada needs, he said, is a licensing program such as other states have for off-roaders to educate them about the importance of preventing terrain damage and preserving resources.

Hall said although that would be a step in the right direction, Gold Butte is a special place that needs better management in the form of a conservation area adjacent to wild lands.

"The area has resources, natural, cultural and historical, in proportion of a national park, and there's no protection, no management. It needs to be done now. The BLM has been working on it for 10 years and there's still not anything on the ground.

"If we had a national conservation area with wilderness, we could balance the recreation and education for visitors and a place for Mesquite residents to steward and grow with like Red Rock Canyon is to Las Vegas."

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers @reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.

Audio slide show GETTING THERE To reach Gold Butte from Las Vegas, take Interstate 15 north to the Riverside/Bunkerville exit. Then head southeast, right, on state Route 170 and cross the bridge over the Virgin River. Turn right on a paved road for about 24 miles. The road turns to gravel at Whitney Pockets. Continue south for 19 miles. The Gold Butte town site is at the "Y" intersection.