Nevada widow’s quest: Lost records hamper late Army veteran’s recognition

Jan Millholland thought she knew almost everything about her late husband, but is still learning a lot about his military service.

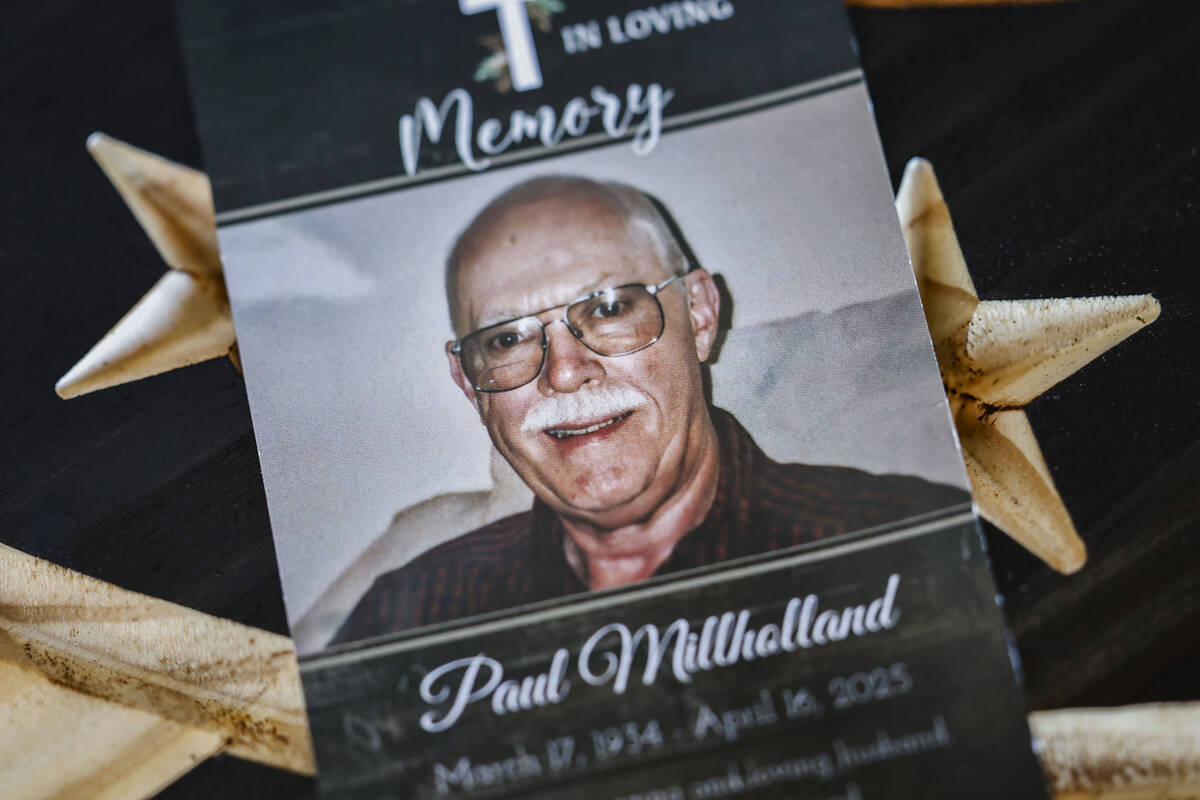

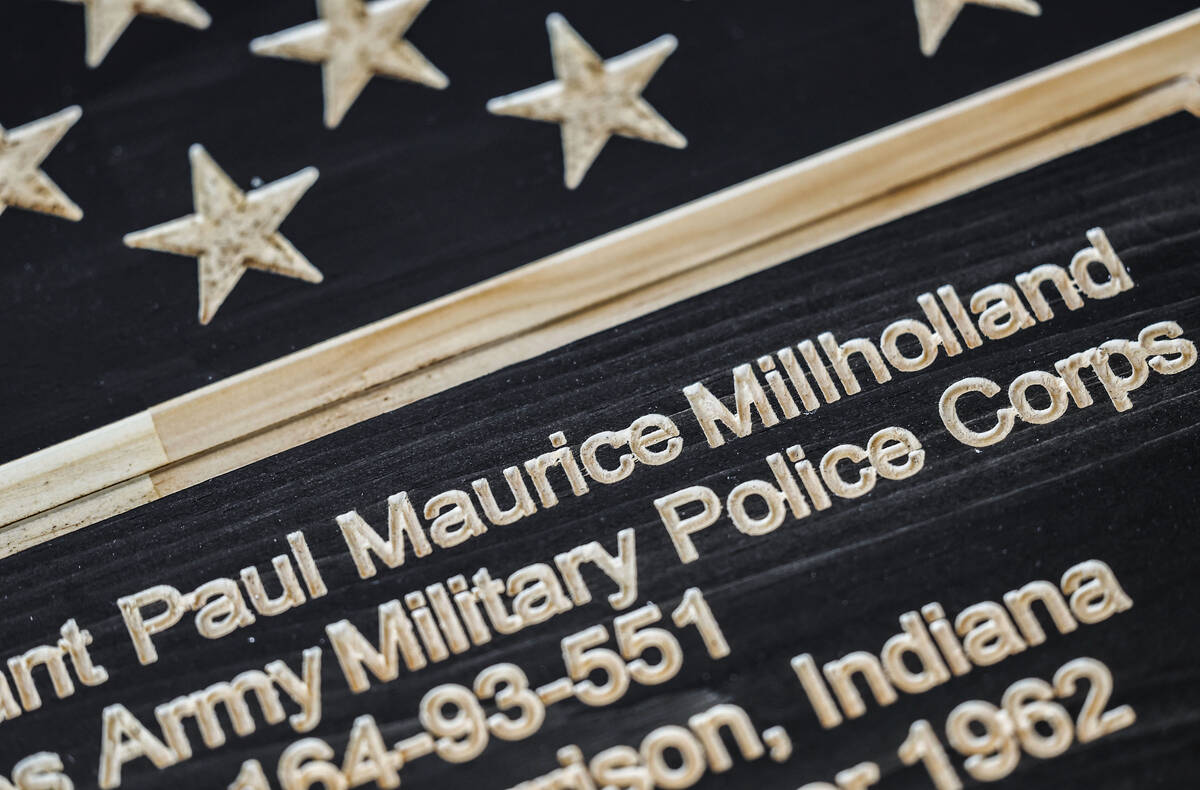

At 91, Paul Millholland died April 16 at the Henderson Hospital from respiratory failure, pneumonia and other complications. But long before that, he crafted a decades-long career as an executive at a pharmaceutical manufacturer in Michigan. Before that, he was a staff sergeant who served for eight years in the Army’s Military Police Corps.

“He was a very religious fellow,” 76-year-old Jan Millholland said of her husband, though he seldom talked about his experience in the service. A few keepsakes remain from Paul Millholland’s service in the family’s home in Henderson, notably his dog tags, a few photographs of him in uniform and a discharge certificate dated Oct. 10, 1962, according to his widow.

“I didn’t even know he was a veteran until I was probably in my early to mid-20s,” said Paul and Jan’s 28-year-old daughter, Savanna Millholland.

When the couple moved to Southern Nevada in 1995, they learned the federal government had no record of Paul Millholland’s Army service when he was denied a special homeowner’s loan via the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

They later learned that Paul Millholland’s military file was destroyed in a sprawling 1973 fire at the Military Personnel Records Center near St. Louis, which, according to The Associated Press, is believed to be the largest loss of records in a single catastrophe in U.S. history.

The 1973 fire at the Military Personnel Records Center near St. Louis destroyed an estimated 16 to 18 million military personnel files, according to the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, including files for about 80 percent of Army personnel discharged between Nov. 1, 1912, and Jan. 1, 1960, according to the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. The fire also destroyed records for about 75 percent of Air Force personnel discharged from Sept. 25, 1947, through 1963.

The Millhollands got their mortgage elsewhere, though Paul Millholland was never able to learn more about why his service went unrecognized, Jan Millholland said. During a stretch from 2018 to 2019, the Millhollands tried contacting officials at the VA, local lawmakers and other federal agencies to no avail.

“Basically, nobody did anything,” Jan Millholland said. “After several attempts and letters that he (Paul Millholland) wrote, he just kind of gave up.”

Following Paul Millholland’s death, Jan Millholland figures a renewed push to acknowledge her late husband’s military service and scatter his ashes at the Southern Nevada Veterans Memorial Cemetery in Boulder City would bring the closure and the benefits she believes her late husband deserves.

“He was very proud,” Jan Millholland said of his time in the reserve. “He had hoped to be buried in Boulder City.”

Veteran steps in

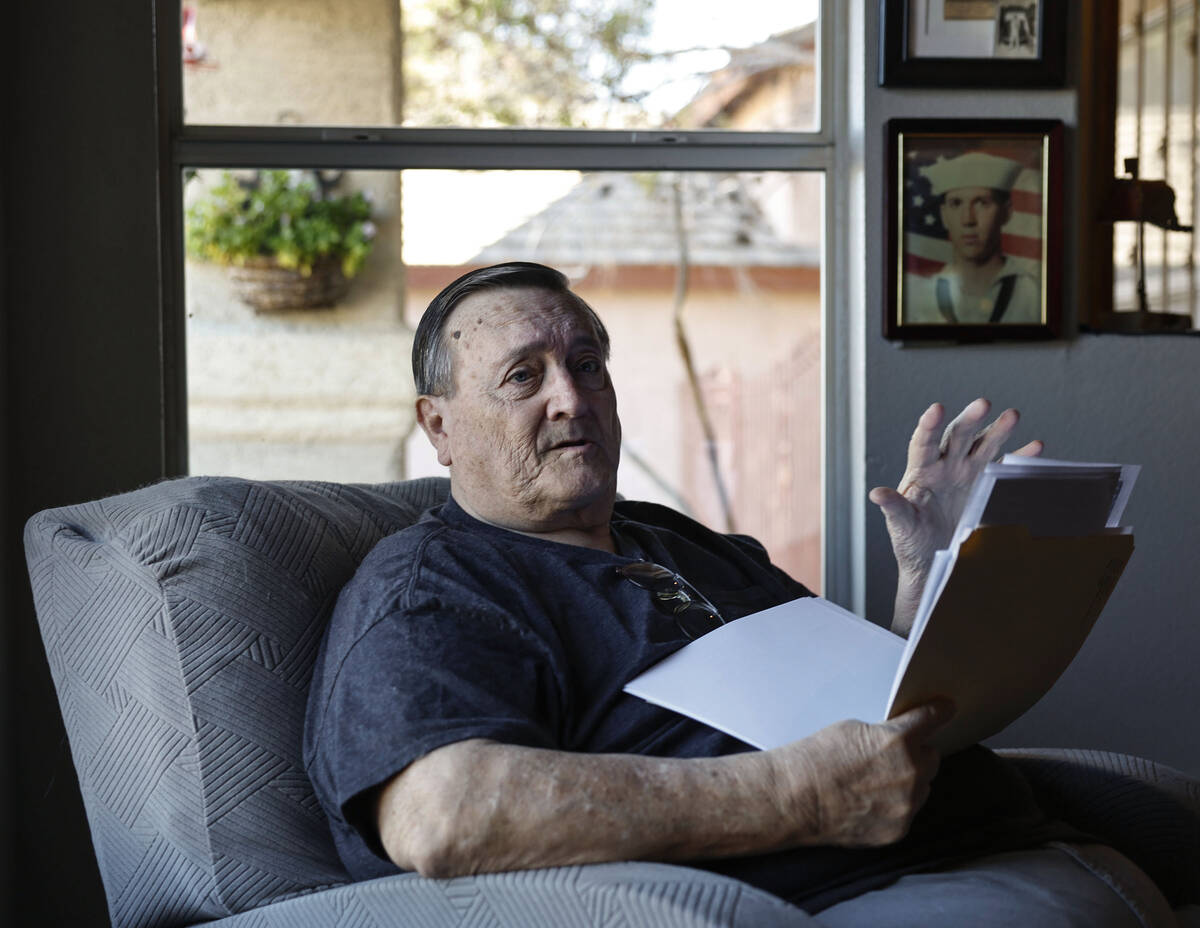

Days after Paul Millholland’s death, Jan Millholland was introduced by a mutual friend to James Born, a neighbor and veteran who has become a catalyst in her quest for her husband’s posthumous recognition.

Born, 79, is a former longtime private investigator and former Navy petty officer first class and retired Army master sergeant who happened to live just a few doors down. Born learned from Millholland about her situation and almost immediately sprang into action, she said.

On April 28, less than two weeks after Paul Millholland’s death, Born sent a letter to President Donald Trump explaining the situation, along with key information Born has learned parsing through what little military records Jan Millholland still has from her late husband, like Paul Millholland’s service number, enlistment and discharge dates, the unit he served, and other vital personal information. He said he figures that information can be cross-referenced with records at other agencies.

But like Paul Millholland before him, Born has also tried reaching out to the VA and National Archives in hopes of initiating the process to verify Millholland’s service. He has yet to receive any reason to believe his inquiries are being worked on.

“Not a callback, not an email,” Born said, except for one inquiry sent to the newly renamed Department of War.

“I sent one directly to them and someone responded immediately back, but he said he was sending it over to another agency. The other agency didn’t bother calling back.”

Terri Hendry, public information officer for the Nevada Department of Veterans Services, said in an email Friday that the 1973 fire affected many veterans and their families, which has resulted in challenges when applying for benefits or burial eligibility.

The state agency also works with so-called Veteran Service Officers, individuals who are accredited to assist veterans and families affected by the loss of records, Hendry said, adding the agency would be happy to assist the Millholland family. Caseworkers do that by verifying service information from alternate means, such as unit rosters, pay records, morning military reports, and other documents.

“While the process can take time, our goal is to ensure every Nevada veteran and their family receives the recognition and benefits they have earned, particularly in cases where documentation has been lost through no fault of their own,” Hendry said.

On Monday, Born reached out in hopes of getting some answers.

Finding closure

Pete Kasperowicz, press secretary at the VA, said in an email that privacy laws prevent the agency from discussing specific cases, but recommended a section on the VA’s website offering guidance on reconstructing military records destroyed in the ’73 fire. Neither he nor a National Archives spokesperson responded to questions about how many veterans had trouble receiving benefits as a result of the fire.

The webpage contains information such as a National Archives form that can be used to search for supporting documents from military archives and other government agencies to verify proof of service, as well as a tool to check the status of a claim. The VA recommends contacting a professional, such as a Veterans Service Officer, for claims involving record reconstruction.

Personal documents, like letters or photographs from someone’s time in the service, may also be used to consider a claim, according to the VA.

That means Paul Millholland’s case should be one that is open-and-shut, Born and the Millhollands say. With multiple photos of Paul Millholland in his Army uniform, along with his dog tags and certificate of honorable discharge, the Millhollands said they’re optimistic.

“I would be real relieved that he finally got the recognition that he deserved,” Savanna Millholland said. “He was a hardworking man, even up till his last breath, so I would just be relieved and happy that he finally got it, and that we can all finally be able to relax knowing that he got everything he deserved.”

A previous version of this story misstated James Born’s military service.

Contact Casey Harrison at charrison@reviewjournal.com. Follow @casey-harrison.bsky.social on Bluesky.