FULL MILITARY HONORS

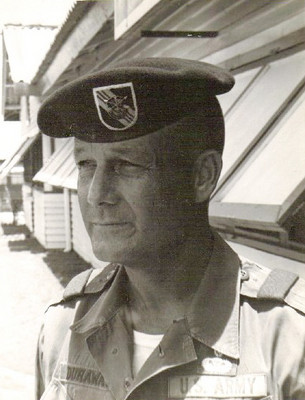

WASHINGTON -- With a chilly March breeze under an overcast sky, six white horses pulled a caisson holding the coffin of George W. Dunaway, who was buried with full military honors Wednesday at Arlington National Cemetery.

The click clack of the horses' hooves meshed with the pounding drum of a marching military band as the procession arrived shortly before 10 a.m. at Section 34, Gravesite 141-A1.

It was somewhat of a homecoming for Dunaway, who was born July 24, 1922, in Richmond, Va., and earned the distinction of becoming the second man to serve as sergeant major of the Army.

Dunaway, who retired to Las Vegas 22 years ago, died last month at Valley Hospital after suffering a series of heart attacks. He was 85.

"It's just the toughest death I've experienced in my life, tougher on me than my own father's death," said 70-year-old Fred Marshall, a retired Army officer who lives in Humboldt, Tenn.

Marshall, who was the chief assistant to Dunaway when he served as sergeant major from 1968 to 1970, struggled on crutches to climb the hill where his former boss would be laid to rest.

"If you asked George Dunaway a question and asked me the same question, I could tell you what he would say nine times out of 10," Marshall said.

Dunaway restored the honor of the sergeant major's office after his predecessor, William O. Wooldridge, was charged with fraud and corruption for selling merchandise and alcohol at noncommissioned officer clubs in Vietnam from 1966 to 1968.

In a distinguished military career that spanned World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War, Dunaway received the Bronze Star, the Silver Star and the Purple Heart.

"Very few people are buried with full military honors, and to see this given to my father is really impressive. I can't put into words what it means. I know he would be proud," said his son Michael Dunaway, 62, of Las Vegas.

Near the entrance of the historic cemetery, women dressed in black protested the fifth anniversary of the war in Iraq by wearing white placards with the names of Americans killed in the war.

It was so cloudy that cars in Dunaway's funeral procession had their headlights on as they arrived at the burial site.

After eight soldiers in dress blue uniforms trudged up the hill with Dunaway's coffin, a squad of seven soldiers stationed below the hill and across a paved road fired three volleys. This was followed by taps, played by a bugler nearby.

The soldiers who carried Dunaway's coffin held a U.S. flag still over it as a distant clock tower tolled 10 a.m.

As family members sat near the grave, the soldiers folded the flag and handed it to the 13th sergeant major of the Army, Kenneth O. Preston.

Preston presented the flag to Dunaway's widow, Mary. Her husband died the day before they would have celebrated their 65th wedding anniversary.

The ceremony ended at 10:10 a.m. as about 75 spectators were cautioned to "watch your step" as they descended the hill where Dunaway would remain in his final resting place.

"My father always spoke of the honor of being buried at Arlington National Cemetery among his fellow soldiers," said his 52-year-old son, George, who graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1978 and lives in Wichita Falls, Texas.

"Today was the end of a long and storied career."

Contact Stephens Washington Bureau reporter Tony Batt at tbatt@stephensmedia.com or (202) 783-1760.