Historical Perspective

MOJAVE NATIONAL PRESERVE, Calif. -- By the time George Lowell was born, Kelso Depot's best days were behind it.

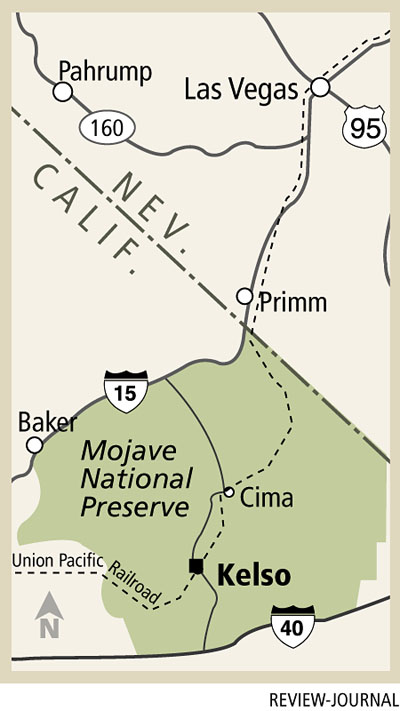

World War II had just ended, and the diesel locomotive would soon replace the steam engine, spelling the end for this Union Pacific water stop 95 miles south of Las Vegas.

Lowell was too young to remember those days. When he set out to build a scale model of the depot and small town where he spent the first four years of his life, he had to rely on photographs, blueprints and the memories of others.

The finished product went on display this week at the depot-turned-visitors center for the 1.6-million acre Mojave National Preserve, just across the Nevada border in California.

Lowell spent 16 months and about $2,000 on his intricate re-creation of Kelso in its heyday. Then he donated the whole thing to the Park Service.

An informal dedication ceremony, complete with cake, will be at noon today at the three-story, Spanish Mission Revival-style depot.

"I just got a whim to do it," the 62-year-old retired hospital engineer said. "I got what you call a wild hair up your tail feathers."

The model is 8 feet wide and 12 feet long and includes 140 buildings, several feet of track and numerous trains.

It depicts Kelso as it looked from 1940 to 1945, when the depot was abuzz with wartime activity.

Trains rattled through the area day and night back then, many of them loaded with soldiers and materiel, including iron ore from the nearby Vulcan Mine. "Helper" locomotives based at the depot were used to pull the trains up the 2,100-foot grade between Kelso and Cima.

Lowell's grandfather drove one of those helper engines. The small, railroad-owned house where he lived is marked on the model of Kelso with a car and a tree out front and a clothesline out back.

Three doors down is a replica of the canary yellow house, also company-owned, where Lowell's parents briefly lived before his dad was fired by Union Pacific. After that, the family moved into a converted boxcar, and Lowell's dad found work as a mechanic at the Vulcan Mine.

By the time the Lowells left Kelso for good in 1949, the town was in full retreat from its wartime peak of about 2,000 residents. The mine had closed and the railroad had switched to diesel locomotives that needed no help climbing the grade.

With the helper engines silenced and the water stop gone, the out-of-the-way depot finally closed in August 1964, though its lunch counter continued to operate until July 1985.

Union Pacific eventually sold the land to the federal government, and the depot reopened as the preserve's visitor center in 2005, after $5.1 million worth of renovations.

To build his model, Lowell relied on whatever historic photographs and survey documents he could find. He filled in the blanks with measurements he took himself of the depot and its proximity to nearby roads, railroad tracks and other landmarks.

"He's done some amazing research," said park ranger Linda Slater. "He's really made an effort to be authentic."

Slater hopes the display will give visitors an idea of just how much activity there once was in and around the depot.

"People see it now and it looks abandoned," she said. "What it does is it helps convey how huge Kelso was."

The model is built in what railroad hobbyists know as N-scale, where an inch equals 13 feet and tiny, plastic people stand no taller than a thumbtack.

The details are meticulous, right down to piles of rails and wooden ties in the background of a few of the pictures Lowell used for reference.

His wife, Lisa, strung power lines made of black thread and stocked the tiny corrals with tiny piles of alfalfa for the tiny cows to eat.

Lowell shrunk an old ad for Mobil oil to about half the size of a postage stamp and pasted it to the wall of the store and dance hall his grandmother owned near their house in Kelso.

A few items had to be special ordered, including a row of trailers that were re-created by a model maker in the Midwest based on an old photograph Lowell e-mailed him. They cost $18 each, and came as kits that Lowell had to assemble.

Almost everything else Lowell fashioned himself out of balsa wood, model glue and a great deal of patience.

The depot alone took him three obscenity-laden months to build because the arches kept snapping on him.

"I reverted back to my old sailor days," he said with a grin.

Nearly all of the work was done in an air-conditioned shed behind the Lowells' Apache Junction, Ariz., home.

He and Lisa applied the finishing touches to the display in the depot's basement on Sunday.

As they worked, a few park visitors stopped in to check their progress.

One of them was Diana Palmer, whose grandmother and great-grandparents lived in Kelso a decade before the depot was built in 1924.

Palmer showed Lowell an album full of old pictures documenting her family's time in the area. Then she pointed out the approximate spot on the model where their modest home once stood.

"I'm going to build that house," Lowell promised.

He should have plenty of time to get the job done. The Lowells are scheduled to spend the next three weeks working as volunteers for the Park Service in Kelso.

If that works out, they plan to return each year at this time and spend a few weeks helping out around the depot. They've even considered buying a piece of private property within the preserve and making it their seasonal home.

"I love meeting people and telling them stories about things I know," Lowell said. "This town has given me my thrill."

Contact reporter Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or (702) 383-0350.