Indian team names: No problem for some Native Americans, irritant for others

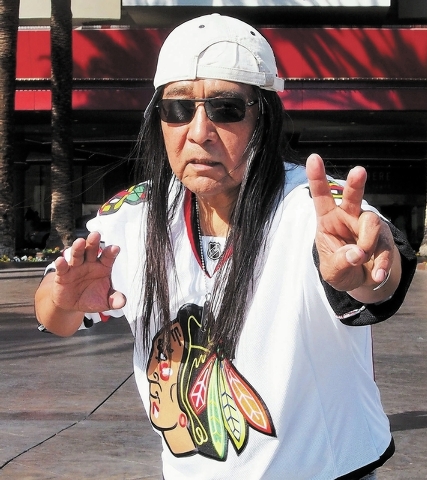

L eon Yazzie speaks fluent Navajo. He grew up on the Navajo Nation in northeastern Arizona. His grandfather was a medicine man.

During World War II, his uncle was a Navajo code talker. He and other Navajos used the highly complex language to communicate to the U.S. Marines, letting them know where their next attack would be in the Pacific. The Japanese never saw it coming. They could never decipher it.

The 45-year-old long-haired Yazzie is proud to be Navajo, and he’s proud to be an “American Indian.”

He’s also proud of the Chicago Blackhawks, the professional hockey team. Not because he follows the sport so much or knows a great deal of history about Chief Black Hawk, who sided with the British and fought against European-American settlers in Illinois back in the early 1800s.

No, he just digs the jersey with Chief Black Hawk’s caricature on the front.

Yazzie says it helps give the public a sense of who he is. He wears it around town any chance he can get.

And he doesn’t understand all the controversy regarding the sports teams and their logos. He doesn’t get the fuss over fans dressing up in war paint and feathered headdresses while they root for their Washington Redskins, their Kansas City Chiefs, their Atlanta Braves, their Cleveland Indians.

This is America, after all. The Indians were the first to inhabit it. Virtually every corner is full of Native American names, from the rivers to the lakes to the streams to the hillsides to the mountains to cookie cutter subdivisions, he says.

He even cracks a joke about the ongoing debate as to whether the Washington Redskins, the NFL team, should change what many see is a racially charged moniker and replace it with the logo of a bunch of “red skin” potatoes, which have been known to be handed out before games by Indian tribes offended by the logo.

“Just take away the ‘Washington,’ and leave the ‘Redskins,’ ” he says from behind the counter of the pawn shop where he works every day. “Then everyone will be fine, I think.”

Then, in a more serious tone, Yazzie says what he really thinks.

“It’s not that I’m not proud of who I am or that I don’t think it’s disparaging at times. But we’re talking about teams that are making millions of dollars off these logos. It’s part of the game, and it’s been going on for a long time. If fans are dressing up like Indians and acting like Indians, then let them. If it happens in movies and it’s displayed in museums, then why should it bother me if it’s happening inside a stadium?”

And so as the NFL enters its 11th week, some of the fans will carry on the antics. They will put on the war paint and Indian headdress in the name of their team. But there will be some Native Americans in the Las Vegas Valley who will be watching from the sidelines, and from their living rooms, with a critical eye.

TOUCHY SUBJECT FOR SOME

Some Native Americans in Las Vegas have had enough of the histrionics. While the mascot controversy overall has managed to skirt Nevada, if only because there are no major professional sports teams with Native American mascots, that doesn’t mean the various tribes, from the Paiutes in Southern Nevada to the Hualapai in Northern Arizona, are on board with it all.

Many local Native Americans have opinions about it, and not all opinions are as accepting as Yazzie’s.

“When you see these people do the tomahawk chop, it’s just silly,” said Tracey Miller, 41, a Moapa Paiute, referring to the fans of the Atlanta Braves during their rallies.

“It’s a stereotype. Nobody likes to be thought of as something less than what they really are. Our culture is a lot more complex than the tomahawk chop. I’ve had people ask me, literally, if I lived in a teepee, and I tell them, ‘Yeah, if I was a Plains Indian in the Dakotas or Montana, I would have lived in a teepee. But not in Nevada. That never happened.’”

Yet Miller lived across the street from Western High School as a child before he moved to the reservation, and says he doesn’t remember being offended by the high school’s mascot, the warrior. Every day, in the 1980s, he said he’d see the warrior statue in front of the high school, and never gave it a second thought.

“Maybe it’s because he had this proud warrior stance,” Miller said, trying to figure it out. “I think it was just the way it was depicted. It looked like a real warrior, and nobody was dressing up and painting their faces at the games and making a mockery of our culture.”

Unfortunately, the Native American culture is far too often described by the outsider and not by those who would know: the Native American people themselves, notes Susan Power, a nationally acclaimed author.

Power, who grew up in Chicago and now resides in St. Paul, MN., wrote “The Grass Dancer,” a book that was published in 1994 and weaves tales of ghostly ancestral visits from the 1860s to the 1980s on the Sioux Reservation.

“Native peoples have figured prominently in the public imagination for hundreds of years now,” says Power, a member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. “People who are not Native American have been telling us who we are, who we should be, for the same length of time. When do we get our chance to define ourselves and tell the rest of the world our own stories in our own voices?”

She then quotes Vine Deloria Jr., a Dakota writer and philosopher who wrote “We Talk, You Listen,” a book that was published in 1970 and explores racial conflict and stereotypes that still persist, not just among Native Americans, but blacks, Hispanics, hippies, even the feminists:

“If people would listen to us and absorb what we’re saying, they’d hear how sick and tired we are of being your imagined creatures. We are not your playthings, your mascots, your underlings, your exotic primitive pawns! We are fellow citizens and the original occupants of this territory who ask for your respect which has been a long time coming. Enough with the mascots, already — change the name!”

Dawn Bruce, who runs the social service programs on the Moapa River Reservation, is not a Paiute. She’s originally from North Dakota, and her feelings on the misuse of Native American mascots runs deep. She recalls how one day she heard a white college student from the University of North Dakota exclaim how much she was going to miss the “Fighting Sioux” mascot, which was banned from the university.

“I remember her saying, ‘But this is all I’ve ever known. This is who we are. We are, ‘the Fighting Sioux,’ ” recounts Bruce, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians from Belcourt, N.D. “And all I could think of was how she didn’t really have a clue. The Fighting Sioux isn’t who she is. It’s who the Sioux people are.”

There are some Sioux who take pride in the mascot, the fact that the tribe, in essence, is the poster child for a college football team, Bruce says. But there’s also a segment of the Native American society that is deeply offended by it when fans start to dress up and exaggerate the customs and the costumes of those who are truly Sioux, Bruce says.

And the solution is simple enough: In the future, if a college, university or professional ballclub wants to name a mascot after a Native American tribe or symbol, then they should ask the tribe for its permission first.

“End of story,” she says. “Don’t you think that’s the right way to do things?”

TRIBAL SYMBOL TO TOUT

Randy Meyers, a Paiute in the Moapa Valley, tries not to take the whole mascot issue too personally. It’s just a way of life, and there’s not much he can do about it from where he sits, inside his modest house on the Moapa River Reservation.

He sleeps in a bed laid out in the living room. He lives in the shadows of a power plant. Life is slow for the 59-year-old diabetic. He has more on his mind these days than trying to change the way people think about the Native American cultures.

And he has a favorite mascot. It’s not the Cheese Head from the Green Bay Packers, his favorite football team.

No, it’s the desert ram. It happens to be the symbol for the Moapa Band of Paiutes. It’s on all of the tribe’s police cars and stationery.

“I keep trying to tell them to get it enlarged, so it shows up bigger on the cars,” he says.

The desert ram also happens to be Rancho High School’s mascot.

Meyers graduated from there in 1974. He still has the school T-shirt.

“The ram is our sacred animal,” says Meyers, speaking of the tribe. “The coyote is the trickster, the jokester; and the wolf is our protector. The owl brings bad news, death, stuff like that.

“Our tribe used to go behind the gypsum mines behind the Sunrise and Frenchman mountains where they would have visions. That was the old way. I learned that from my dad.”

What would his father think of all the controversy?

“He wouldn’t have time for it,” Meyers says. “He’d be too busy looking for new medicines near the gypsum mines. He found one rock where the dirt off it helped cure acne. I swear.”

Contact reporter Tom Ragan at tragan@reviewjournal.com or 702-224-5512.