Maryanski had dream for college

For now, e-mails sent to Fred Maryanski, the Nevada State College president who died last month, get forwarded automatically to Lesley Di Mare, the provost.

Nevada State is very small, with 2,500 students and 140 full-time employees. Pretty much everybody who works there knows everybody else who works there by name. It is a cliché, but they all say they feel like family.

Di Mare has even joked that she saw Maryanski more than she saw her husband.

That is why it is momentarily uncomfortable when those e-mails appear in Di Mare's inbox. A quirk in the computer system makes it appear as if they are coming from Maryanski himself.

Briefly, it seems as if he is still e-mailing at all hours of the day and night. That's one of the things Maryanski used to do. He would get an idea and e-mail someone about it. It was not that he was obsessed with his job; it was that he was dedicated to it.

In one of his last acts, Maryanski debuted the results of the last several years of his work: the four-year college's master plan.

The plan's scores of pages lay out a future where the college is as integrated into the community as is the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

The plan may well be Maryanski's longest lasting legacy.

During his five-year tenure, Nevada State College's enrollment grew 61 percent; he brought stability to a school that had seen four presidents in its first three years of existence; and he solidified the college's mission as one where serving first generation and minority students took precedence.

But the Nevada State College master plan envisions more. Much more. It envisions:

■ 25,000 students;

■ 6 million square feet of building space;

■ 10,000 parking spaces;

■ Housing for up to 5,000 students;

■ Athletic fields, a bookstore, a wellness center and full integration with adjacent city of Henderson facilities.

It is a bold plan that might -- or might not -- ever happen.

"It expresses an excitingly vibrant image of what the college should and could be," said Dan Klaich, the state's higher education chancellor.

Klaich said he will soon be meeting with faculty, staff and students at the college to ask them what they would like to see in a new president. He expects to recommend an interim president in September. It could be a year or more before a permanent president is chosen.

Klaich said he expects the interim president will be someone already familiar with the state and the college, though he did not name any potential candidates.

Maryanski left a solid foundation for whomever the higher education board chooses as president.

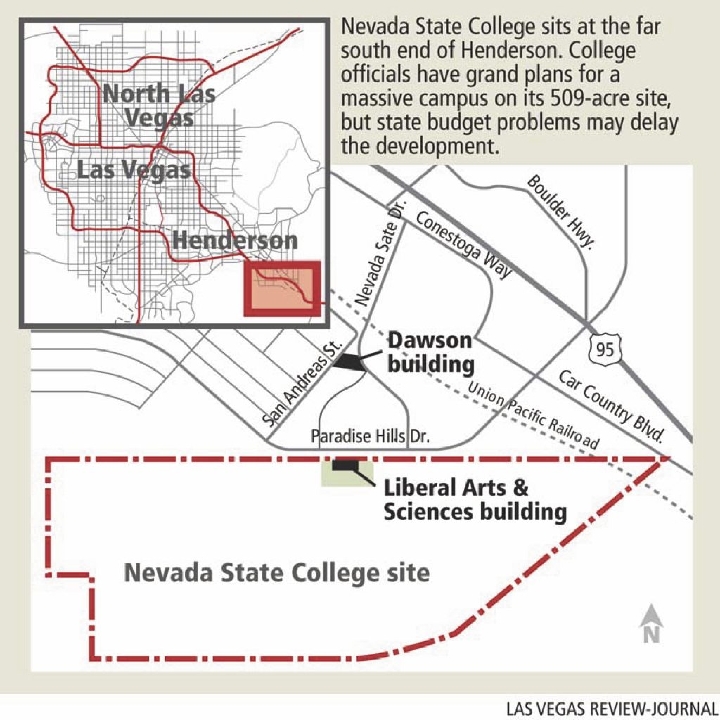

The college is far from firmly established, however, with just one permanent building sitting alone on 509 acres of mountainous desert terrain at the far south end of Henderson.

Other parts of the college are housed in a nearby refurbished vitamin factory and in a strip mall in downtown Henderson.

It has graduated just more than 1,000 students, mostly in nursing and teaching, its primary reason for existence.

Since the recession began and kicked the butt of state government funds, the college has had to deal with persistent rumors that it will someday be shut down to save money. That's despite its minuscule budget when compared to the overall higher education budget in the state.

The college's entire state-supported operating budget of about $16 million is 2 percent of the higher education system's overall state-supported operating budget for 2009-2010.

So, the college and its people persist. They plan for a bright future, even though they know it will be delayed until the economy picks up.

Buster Neel, the vice president for finance and administration, said one thing the college has in overabundance is land. Those 509 acres are more than it needs. The campus is 50 percent larger than UNLV's main campus.

About 150 acres could be split off from the campus and leased to private industry. Maybe to a new elementary or middle school, medical facilities, a green technology park, even to developers if the day returns when people want to build houses again in Southern Nevada.

What's nice is the state declared the campus a "tax increment area," which means the school gets to keep whatever property taxes get generated on the site. In other words, school officials could use all that extra land to make money to help build the rest of the campus.

A new building for the college has been ranked among the top funding priorities by the states' higher education leaders. But the likelihood of getting money from lawmakers anytime soon seems low. Officials expect the state could be somewhere near $3 billion short next year of where it needs to be.

The progress, then, will be slow. But there will be progress. College officials say enrollment is likely to rise again this fall, as it has every fall since the school opened in 2002.

Someday, there will be another building. And then another. If all goes according to Maryanski's master plan, there will be five new buildings in the foreseeable future and many more to come.

If that happens, if the school really does top out at 25,000 students some day, it will all be done in a sustainable way. Maryanski's plan dictates a "carbon neutral" campus. Recycling, the use of renewable energy, and efficiency will be top priorities.

There could be a private health care facility on the campus, too. Nursing students would work closely with the facility. The same would be true if a school were built there. Teaching students would benefit.

Someday, if all goes according to plan, Nevada State College could be a thriving campus in the way the state colleges in California are. It could ease the burden on UNLV, allowing the university to spend more energy focusing on research. The state college would feed it graduate students.

That is the dream Maryanski had.

Contact reporter Richard Lake at rlake@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0307.