High-stakes health-care debate hits Nevada’s Medicaid program

CARSON CITY — Marta Jensen, Nevada’s point person on Medicaid, watched on C-SPAN recently as the U.S. Senate debated health care reform. She had four different bills pulled up on her computer.

The stakes were high for Nevada. Each of the bills would have repealed at least parts of the Affordable Care Act and affected Medicaid, the federal-state program that provides poor and disabled Americans with medical coverage. More than one-fifth of the state’s residents now receive their health insurance through Medicaid.

When the session ended days later, senators had voted down all of the measures. For Jensen, following the debate was like reading a novel with frequent plot twists — but missing its final chapters.

“Obviously, we’re very concerned that the expanded population may go uninsured again,” said Jensen, administrator of the State Medicaid Office. “That will undermine every activity that we have put into place over the last several years to improve the health care system, not just Medicaid but the state as a whole.”

Medicaid, created under President Lyndon Johnson in 1965, has sharply divided Republicans and Democrats in their efforts to slow spiraling U.S. health care costs without putting tens of millions of Americans at risk of avoidable illness or premature death.

Program growth

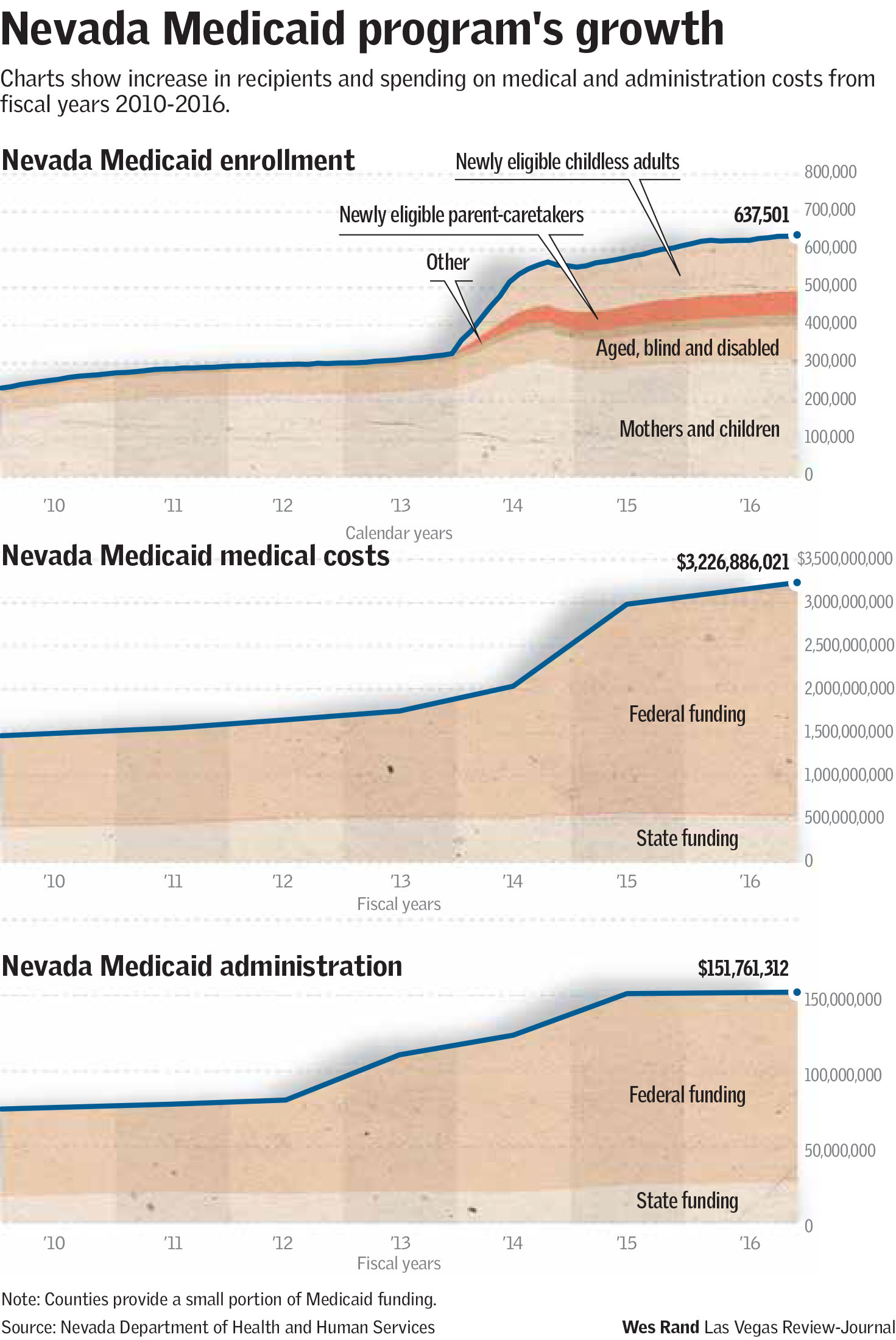

Nevada expanded its Medicaid program in 2014 as authorized by the ACA, adding some 210,000 residents to its rolls. As a result, hundreds of millions of additional federal dollars flow through the program into Nevada’s health care system annually. In total, 637,795 Nevadans were enrolled in the program as of June, an increase of 175 percent from the 231,923 who participated in 2010.

While the political threat to the program has at least temporarily eased, with the Republican-led Congress turning to tax reform and other matters, it is far from over.

Medicaid has become a political punching bag because its expansion came under the Affordable Care Act of 2010, popularly known as Obamacare, a key part of former President Barack Obama’s legacy. Many Republicans have waged a seven-year battle — so far unsuccessful — to repeal and replace it with a different health care policy.

In addition to any possible political motives, GOP opposition to the program focuses on what fiscal conservatives see as an unsustainable increase in federal spending on health care, including Medicaid. They say they don’t want to eliminate the program, but merely slow its growth.

“Generally speaking, we spend more every single year on Medicaid,” Mick Mulvaney, the White House budget director, was quoted by The New York Times as saying in June. “We are not gutting or filleting or kicking people off those programs. We are trying to slow the rate of growth of government.”

A large part of their concern stems from the ACA, which led 31 states, including Nevada, and the District of Columbia to expand their Medicaid programs.

‘The bigger issue’

“What we should be focusing on is how do we make health care affordable for someone to pay their own way,” said Michael Schaus, a spokesman for the conservative Nevada Policy Research Institute, which opposed the state’s Medicaid expansion. “That’s the bigger issue.”

A look at the provisions of the ACA that allowed the expansion makes it clear why so many states jumped at the opportunity.

Under the traditional or “legacy” Medicaid program, states cover about 35 percent of Medicaid spending, with federal dollars covering the remaining 65 percent, except for a small percentage contributed by counties.

States get a much better deal under the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, which primarily targets childless adults. In that case, the federal government pays 95 percent of the costs – down from the 100 percent it originally paid — and the state is responsible for the remaining 5 percent. For Nevada, the difference between funding formulas amounts to savings of about $300 million annually.

If the ACA remains in place, the state’s share of the expansion costs will be capped at 10 percent in 2020 and not increase further. If it’s repealed or replaced, there’s no guarantee that any federal funding would be provided to cover the people who received insurance as a result of the expansion.

Medicaid is often presented as a partisan, Republicans vs. Democrats issue, but Nevada’s politics defy that simplistic characterization.

Nevada Gov. Brian Sandoval in 2013 became the first Republican governor in the nation to approve a Medicaid expansion, a move that was later repeated in 10 other states with Republican executives.

“It was an offer that was too good to refuse, despite the partisan politics,” said Jon Sasser, a longtime lobbyist for Washoe Legal Services and the Legal Aid Center of Southern Nevada. “I appreciate the governor recognizing that.”

Rate of uninsured halved

Mike Willden, Sandoval’s chief of staff and head of the Nevada Department of Health and Human Services when the state embarked on its Medicaid expansion, said the original goal was to drive down the state’s uninsured rate of 23 percent to a 10 to 12 percent range. That goal was accomplished: Nevada’s uninsured rate was 11 percent in 2015, according to a University Medical Center report.

The ACA had another provision that added Nevadans to the Medicaid rolls. An unknown number of people who previously qualified for the program signed up starting in 2014 to avoid paying the tax penalties mandated by the act.

State officials and advocates for the expansion say it has cascading positive impacts.

The most basic is that those with coverage are more likely to see a doctor regularly instead of going to an emergency room for a problem that could have been addressed sooner. That in turn helps hospitals avoid the losses of uncompensated care.

State statistics show about 66 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled through the expansion are accessing medical services. Removing them would likely return them to the emergency room cycle.

“They can’t afford health care and the concern would be going forward, if they’re removed off Medicaid, they really don’t make enough to pay the premium for a commercial product,” Jensen said.

Trickle-down impacts

Willden points to the financial performance of Nevada’s behavioral health clinics, which are funded by state dollars, as an example of the trickle-down impacts. Before the expansion, less than 30 percent of patients had a Medicaid card, meaning the clinics often absorbed the cost of providing uncompensated care. In 2014, the first year of the expansion, that rate increased to about 75 percent of patients, he said.

Mason VanHouweling, chief executive officer of University Medical Center in Las Vegas, said the public hospital has seen a drop in emergency room visits and an increase in patients who make regular visits to primary care doctors for wellness checks and outpatient procedures.

“It’s improved the access for our community to health care and we have seen at UMC not only healthier people, but also improved outcomes because they have follow-up care after their admission,” he said.

He said UMC leadership was concerned and closely monitored all options presented during the recent debate in Congress.

Any of the plans “would significantly be a step backwards for the progress of our state and shut out tens of thousands of Nevadans without coverage and severely limit access to basic health care,” all while driving up premium costs and out-of-pocket expenses for people with private insurance, he said.

Contact Ben Botkin at bbotkin@reviewjournal.com or 775-461-0661. Follow @BenBotkin1 on Twitter.

Who's eligible for Medicaid

Medicaid provides health coverage for some low-income people, families and children, pregnant women, the elderly, and people with disabilities.

In order for low-income adults and children to qualify for Medicaid, the household must have an income limit of up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level. That works out to $1,366 a month for individuals, $1,842 a month for a household of two or $2,795 for a household of four. Other programs, such as Nevada Check Up for children, can help people with higher income limits.

Applications can be submitted by phone, fax, mail and online, or in person at any of the 26 offices of the Nevada Division of Welfare and Supportive Services around the state.

The agency handles the front-end of Medicaid, determining the eligibility of applicants. Average processing time is 12 days.

"We look at every single category that we can potentially put an individual or applicant on before an individual is denied," said Naomi Lewis, a deputy administrator with the division.

For more details and application forms, visit https://dwss.nv.gov/Medical/2_General_Information/