Rhyolite’s boom was a bust

Editor’s Note: Nevada 150 is a yearlong series highlighting the people, places and things that make up the history of the state.

RHYOLITE

The John S. Cook Bank never closes here. The saloons have vanished, and the town’s school bell hasn’t rung in decades.

But there’s just enough left of the bank’s facade to set a visitor to wondering what might have been had this gold-fever boom town actually had, well, gold. Even in its fleeting heyday, Rhyolite was always more about bull than bullion.

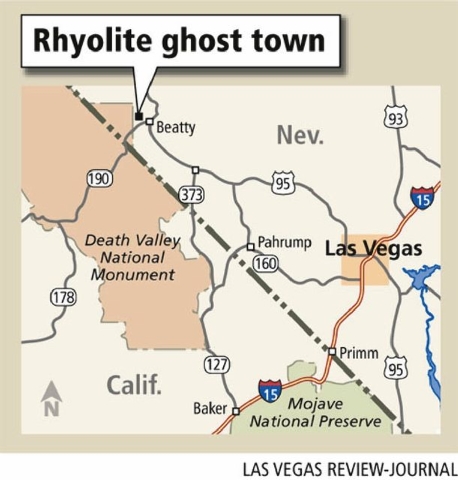

Back in 1905, the promise of a new source of gold drew jackass prospectors, hopeless dreamers and a fair number of speculators to this place, approximately 120 miles northwest of Las Vegas and just a few minutes outside Beatty, not far from Death Valley National Park.

But the fact Rhyolite never lived up to the unadulterated hype that once flowed through its rutted streets like Friday night whiskey only makes it more attractive to devotees of the Silver State’s raucous past as Nevada celebrates its 150th anniversary.

In the wake of the turn-of-the-century silver and gold discoveries in Tonopah and Goldfield, the hunt was on for the next big desert bonanza. Gold was discovered near what would become Rhyolite in the summer of 1904, and the town started to take shape a few months later. Within a year it had 50 saloons, 19 rooming houses and no shortage of brothels.

The Montgomery Shoshone Mine showed elusive promise, but word of Rhyolite’s potential quickly spread. By 1906, namesake Bob Montgomery sold out to steel industry executive Charles M. Schwab, who poured his impressive assets into the bustling metropolis in the Bullfrog Hills near the edge of the Amargosa Desert in what is now part of Nye County.

Nevada had gold fever, but crafty promoters and wide-eyed investors were the ones who broke a sweat when word first began to circulate that Rhyolite quite possibly was the next major score. In no time, Rhyolite had its own newspaper, a rail line, electricity from as far away as Bishop, Calif., and a pricey water supply. By 1907, Schwab could place a telephone call from his new headquarters.

Rhyolite had no shortage of confidence, but it did lack sufficient ore. By 1908, stock investors in the Montgomery mine began to get suspicious about its actual profit potential. It closed in 1911, and Rhyolite’s glory days were behind it.

Its remains, however, have become a popular attraction for Nevada travelers and a place of inspiration for a generation of artists and writers.

At Mel’s Diner in Beatty, waitress Nancy Anderson says visitors from all over the world include Rhyolite on their vacations.

“We’re a tourist town and the Gateway to Death Valley,” she says. “A lot of people do stay in our small town in Beatty, and then they almost always visit Rhyolite.”

The diner’s walls include vintage photos of Beatty and Rhyolite. But some of those who visit its ruins aren’t living in the past.

For Goldwell Open Air Museum executive director Suzanne Hackett-Morgan, the place is a canvas for artists of many mediums. The nonprofit group she leads is dedicated to preserving its history and its artistic flavor.

Several artists are featured at the Goldwell, but the late Polish-Belgian sculptor Albert Szukalski’s “The Last Supper” piece is arguably the most intriguing.

The visual artist again put Rhyolite on the map, and it remained an inspiration for Szukalski to his last days.

“He basically started the whole thing,” she says. “He started it out there and found something that he really enjoyed. He brought out other artists. He told me on his death bed, ‘Suzanne, keep it going.’ ”

And she has. Against long odds, Rhyolite still inspires.

John L. Smith’s column appears Sunday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday. Email him at Smith@reviewjournal.com or call 702-383-0295. Follow him on Twitter @jlnevadasmith.